Restoration Studies in Degraded Pinyon- Mexico

advertisement

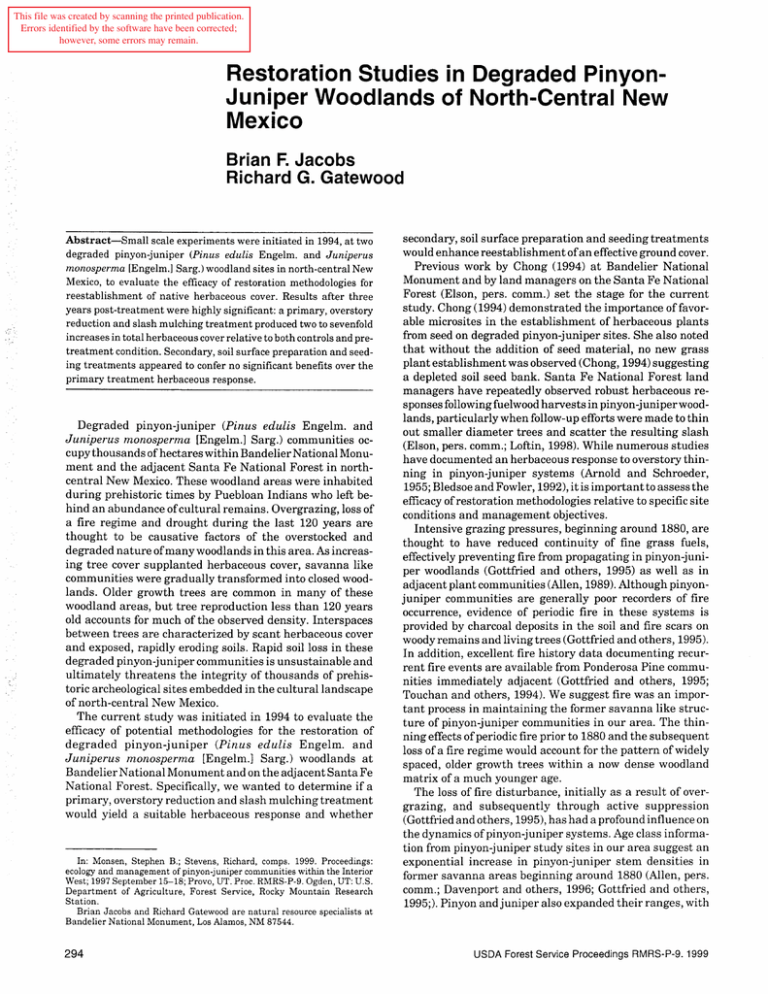

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Restoration Studies in Degraded PinyonJuniper Woodlands of North-Central New Mexico Brian F. Jacobs Richard G. Gatewood Abstract-Small scale experiments were initiated in 1994, at two degraded pinyon-juniper (Pinus edulis Engelm. and Juniperus monosperma [Engelm.l Sarg.) woodland sites in north-central New Mexico, to evaluate the efficacy of resto~ation methodologies for reestablishment of native herbaceous cover. Results after three years post-treatment were highly significant: a primary, overstory reduction and slash mulching treatment produced two to sevenfold increases in total herbaceous cover relative to both controls and pretreatment condition. Secondary, soil surface preparation and seeding treatments appeared to confer no significant benefits over the primary treatment herbaceous response. Degraded pinyon-juniper (Pinus edulis Engelm. and Juniperus monosperma [Engelm.] Sarg.) communities occupy thousands of hectares within Bandelier National Monument and the adjacent Santa Fe National Forest in northcentral New Mexico. These woodland areas were inhabited during prehistoric times by Puebloan Indians who left behind an abundance of cultural remains. Overgrazing, loss of a fire regime and drought during the last 120 years are thought to be causative factors of the overstocked and degraded nature of many woodlands in this area. As increasing tree cover supplanted herbaceous cover, savanna like communities were gradually transformed into closed woodlands. Older growth trees are common in many of these woodland areas, but tree reproduction less than 120 years old accounts for much of the observed density. Interspaces between trees are characterized by scant herbaceous cover and exposed, rapidly eroding soils. Rapid soil loss in these degraded pinyon-juniper communities is unsustainable and ultimately threatens the integrity of thousands of prehistoric archeological sites embedded in the cultural landscape of north-central New Mexico. The current study was initiated in 1994 to evaluate the efficacy of potential methodologies for the restoration of degraded pinyon-juniper (Pinus edulis Engelm. and Juniperus monosperma [Engelm.] Sarg.) woodlands at Bandelier National Monument and on the adjacent Santa Fe National Forest. Specifically, we wanted to determine if a primary, overstory reduction and slash mulching treatment would yield a suitable herbaceous response and whether In: Monsen, Stephen B.; Stevens, Richard, comps. 1999. Proceedings: ecology and management of pinyon-juniper communities within the Interior West; 1997 September 15-18; Provo, UT. Proc. RMRS-P-9. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Brian Jacobs and Richard Gatewood are natural resource specialists at Bandelier National Monument, Los Alamos, NM 87544. 294 secondary, soil surface preparation and seeding treatments would enhance reestablishment of an effective ground cover. Previous work by Chong (1994) at Bandelier National Monument and by land managers on the Santa Fe National Forest (Elson, pers. comm.) set the stage for the current study. Chong (1994) demonstrated the importance of favorable microsites in the establishment of herbaceous plants from seed on degraded pinyon-juniper sites. She also noted that without the addition of seed material, no new grass plant establishment was observed (Chong, 1994) suggesting a depleted soil seed bank. Santa Fe National Forest land managers have repeatedly observed robust herbaceous responses following fuelwood harvests in pinyon-juni per woodlands, particularly when follow-up efforts were made to thin out smaller diameter trees and scatter the resulting slash (Elson, pers. comm.; Loftin, 1998). While numerous studies have documented an herbaceous response to overs tory thinning in pinyon-juniper systems (Arnold and Schroeder, 1955; Bledsoe and Fowler, 1992), itis importantto assess the efficacy of restoration methodologies relative to specific site conditions and management objectives. Intensive grazing pressures, beginning around 1880, are thought to have reduced continuity of fine grass fuels, effectively preventing fire from propagating in pinyon-juniper woodlands (Gottfried and others, 1995) as well as in adjacent plant communities (Allen, 1989). Although pinyonjuniper communities are generally poor recorders of fire occurrence, evidence of periodic fire in these systems is provided by charcoal deposits in the soil and fire scars on woody remains and living trees (Gottfried and others, 1995). In addition, excellent fire history data documenting recurrent fire events are available from Ponderosa Pine communities immediately adjacent (Gottfried and others, 1995; Touchan and others, 1994). We suggest fire was an important process in maintaining the former savanna like structure of pinyon-juniper communities in our area. The thinning effects of periodic fire prior to 1880 and the subsequent loss of a fire regime would account for the pattern of widely spaced, older growth trees within a now dense woodland matrix of a much younger age. The loss of fire disturbance, initially as a result of overgrazing, and subsequently through active suppression (Gottfried and others, 1995), has had a profound influence on the dynamics of pinyon-juniper systems. Age class information from pinyon-juniper study sites in our area suggest an exponential increase in pinyon-juniper stem densities in former savanna areas beginning around 1880 (Allen, pers. comm.; Davenport and others, 1996; Gottfried and others, 1995;). Pinyon and juniper also expanded their ranges, with USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 both species invading upslope into Ponderosa Pine dominated forests and juniper invading downslope into former shrub and grassland communities (Gottfried and others, 1995). Active soil erosion on degraded pinyon-juniper sites during the last fifty years is clearly evidenced by exposed soils and bedrock, soil pedestals, lobes of active sediment and sediment accumulation behind fallen logs (Davenport, 1997). While previous episodes of erosion are documented in soil profiles from local pinyon-juniper sites (Davenport, 1997; Reneau, pers. comm.), the timing of the current erosional episode appears linked to historic land use practices. In addition, an extended drought during the mid-1950's is thought to have intensified competition for water in overstocked woodlands, perhaps reducing herbaceous cover below thresholds necessary to conta~n erosional processes (Wilcox and Breshears, 1995; Wilcox and others, 1996a,b). Occasional trunk remnants of Ponderosa Pine from individ uals killed during the 1950's drought can be found on both sites, but no live Ponderosa Pine is currently present within study site boundaries. Intensive characterization of erosional processes in a one hectare portion of a degraded pinyon-juniper woodland at Bandelier (Wilcox and others, 1996a,b) suggest average annual soil losses of 10,000 to 20,000 kg/ha, most of it occurring during intense thunderstorm events typical ofthe summer monsoons. On the basis of both soil erosion bridge and sediment catchment data, soil loss within degraded pinyon-juniper communities at Bandelier can be conservatively estimated at 2.5 cm per decade; an unsustainable rate given shallow soils with average depths of 1.0 to 12.0 dm (Davenport, 1997; Davenport and others, 1996; Wilcox and Breshears, 1995). Rapid soil loss in degraded pinyon-juniper communities threatens the integrity of the thousands of prehistoric cultural sites located within Bandelier National Monument. Well over three-quarters of the prehistoric sites at Bandelier National Monument occur within pinyon-juniper communities; of these cultural sites, nearly 99 percent have sustained erosional impacts (Mozzillo, in preparation). Despite the cessation of intensive livestock grazing pressure around 1940, in Bandelier National Monument and on portions of the Santa Fe National Forest, degraded pinyonjuniper communities appear to have little capacity to recover. Repeated measures of herbaceous cover in ungulate exclosures established in 1975 on degraded pinyon-juniper sites at Bandelier, suggest exclusion of grazing alone is insufficient to promote recovery of these systems. (Chong, 1992). Overstocked with young trees and lacking an effective ground cover, degraded pinyon-juniper systems are poorly equipped to manage limited soil and water resources. These degraded communities can yield significant amounts of runoff and sediment, at various scales, particularly from bare ground interspaces during high intensity summer thunderstorms (Wilcox and others, 1996a,b). Freeze-thaw action on exposed soils is thought to facilitate erosional processes, both by inhibiting new plant establishment through root shear effects and by creating light textured crusts vulnerable to the forces of wind and rain. Harsh physical site conditions, characterized by exposed, nutrient poor soils, impose severe restrictions on the successful USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 establishment of new herbaceous plants. Soil seed banks appear to be depleted of perennial grass propagules and the depauperate grass individuals are incapable of producing viable seed in many years. With generally low herbaceous productivity, seed predation by birds, rodents, and harvester ants can be very efficient. High levels of mortality are common, in both germinating seed and young herbaceous seedlings. Herbivory of cool season grasses by native ungulates may limit abundance and productivity of these species relative to warm season grasses. At Bandelier, the selection of restoration methodologies is constrained by self-imposed restrictions designed to protect cultural, natural, and wilderness resource values (Sydoriak, 1995). Overstory reduction must be accomplished using minimum tools and techniques that are sensitive to multiple park resources. Rough terrain, high cultural site density, and the presence of designated wilderness essentially preclude mechanized ground disturbing activities (such as chaining, drilling and other agronomic techniques utilizing heavy equipment) typically associated with large scale restoration efforts. Planting methodologies for seed material are generally limited to hand methods. All plant materials must be locally native, requiring custom production at considerable expense. Methodology Two degraded pinyon-juniper sites were included in the current study; one located on Frijoles Mesa within Bandelier National Monument and a second on Garcia Mesa in the adjacent Santa Fe National Forest. Study sites are located at the upper end ofthe pinyon-juniper zone on gently sloped mesas between 1980 m (6600 ft) at Frijoles Mesa and 2160 m (7200 ft) at Garcia Mesa. Canopy closure ranged from 23.0 to 60.0 percent, with herbaceous cover ranging from 5.0 to 15.0 percent, litter ranging from 38.0 to 84.0 percent and bare soil ranging from 7.0 to 56.0 percent. Soils are derived from volcanic ash deposits and are generally shallow and poorly developed (Davenport, 1997; Davenport and others, 1996; Wilcox and Breshears, 1995). Precipitation increases with elevation and ranges from around 40.0 cm. (16 in.) at the Frijoles Mesa site to nearly 50.0 cm. (20 in.) at the Garcia Mesa site (Wilcox and Breshears, 1995). Summer thunderstorms account for nearly half ofthe annual rainfall; winter snows are variable in depth and persistence (Wilcox and Breshears, 1995). Experimental Design The experiment consisted of 18, 15m 2 plots at each of two sites. Because of constraints in implementing this study, the primary, overstory reduction and slash mulching treatment was assigned to 15 contiguous plots, in a non-random fashion, with the remaining three plots serving as controls. Evaluation of the primary treatment relative to controls, is considered separately from the secondary treatment. For the purposes of evaluating secondary treatments, the 15 plots within the bounds of the primary, overstory reduction and slash mulching treatment, were divided into three blocks of five plots each. Within each block, plots were randomly assigned one of five secondary treatment 295 combinations: slash mulch only; slash mulch + imprinting; slash mulch + seeding; slash mulch + imprinting + seeding; or slash mulch + raking + seeding. Data Collection Protocols Herbaceous cover was measured as an indicator of system response to treatment, since these data can be reliably collected by a seasonal workforce and are indicators of available soil moisture and rates of soil erosion. Changes in soil surface cover (that is vegetation, litter, bare soil) were measured using a modified University of New Mexico, Long Term Ecological Research program design; vegetation data was collected by species and growth form and included basal intercept and canopy cover components. Two 21.21 meter vegetation transects were permanently established in each plot for a total of 42.42 m sampled per plot. Pre-treatment data was collected from both study sites during the fall of 1994. Year 2 and 3 post-treatment data was subsequently collected at each study site during the fall of 1996 and 1997. These data were compiled and summarized using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences. Large and small scale repeat photos were taken along the vegetation transects to provide additional visual documentation of treatment response. Restoration Treatments The primary, overstory reduction and slash mulching treatment was applied to both sites in the spring of 1995. Overstory reduction treatment was applied using chainsaws. Bledsoe and Fowler (1992) suggested overstory reduction of pinyon-juniper woodlands through selective thinning, as compared with agronomic techniques such as chaining, can meet multiple management objectives. Main limbs were lopped off and the trunk was flush cut at the base. The resulting slash, lopped branches and trunk sections, were then scattered preferentially.into the bare interspaces to serve as a rough mulch. On the basis of land manager recommendations (Elson, pers. comm.), previous experimental restoration work (Bledsoe and Fowler, 1992), spatial patterns of older growth trees, and water relation studies in pinyon-juniper systems (Breshears and others, 1997), a spacing between mature tree individuals offrom 15 to 20 m was considered optimal for restoration of former pinyonjuniper savanna types in the study area. Following these recommendations, we elected to remove all of the tree canopy within and immediately adjacent to individual plots for the purposes of this small scale experiment. Secondary soil surface preparation and seeding treatments were applied to bare soil areas of both sites during the summer of 1995. Soil surface preparation techniques applied prior to seeding included: no soil surface preparation, light raking, and imprinting. Raking was accomplished using a council fire rake to cut shallow (1-2 cm deep) furrows perpendicular to the slope. Imprinting was accomplished using custom made, hand implements to create a pattern of sloped depressions (5 cm deep) on moist soil surfaces. Imprints provide temporary catchments for seed, litter, soil and water and thus may serve as favorable microsites for germinating plant materials. Seed material was applied at 296 a rate of 1291 seeds/m2 and consisted of a mix of blue gramma (50 percent), little bluestem (30 percent), and sand dropseed (20 percent). The relatively high seeding rate was used in an attempt to compensate for anticipated losses due to seed predation, seed mortality and marginal seedbed preparation. Seeding was accomplished by broadcasting the seed mix onto designated treatment plots subsequent to soil surface preparation. Loose dirt was lightly brushed back into the furrows cut on raked plots. Results _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ Primary Treatment A comparison of the primary, overstory reduction and slash mulching treatment to controls suggests that exposed soil coverage decreased by a mean of 222.0 percent at the Frijoles Mesa site and 200.0 percent at the Garcia Mesa site (fig. 1a,b). Total herbaceous cover had a mean increase of 773.0 percent at Frijoles Mesa and 241.0 percent at Garcia Mesa, by the third year post-treatment (fig. 1a,b). Grass cover increased 446.0 percent at Frijoles Mesa and 179.0 percent at Garcia Mesa (fig. 1c,d), while forbs increased 1267.0 percent at Frijoles Mesa and 705.0 percent at Garcia Mesa (fig. 1c,d). The difference in relative contributions of forbs and grasses at the two sites may be due to the initially high grass cover at Garcia Mesa (25.0 percent) as compared with Frijoles Mesa (6.0 percent). The low initial grass cover at the Frijoles Mesa site may have provided more opportunities for annual and biennial forbs to establish. Secondary Treatment Analysis of the secondary, soil surface preparation and seeding treatments suggest that there was no significant increase in total grass cover over the primary treatment response (fig. 2). While Blue Grama (Bouteloua gracilis [H.B.K.] Lag.) showed a mean increase of 252.0 percent cover on seeded versus 119.0 percent cover on unseeded plots, this increase was apparently offset by contributions to total grass cover on unseeded plots by other non-seeded species (fig. 2). The other two seeded species, Little Blue Stem (Schizachyrium scoparium [Michx] Nash) and Sand Dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus [Torr.] Gray), had mean increases ofless than 1.0 percent across both sites. Discussion ___________ Additional work is clearly needed to more completely understand the mechanisms responsible for the observed herbaceous response. Breshears and others (1997) provide evidence to support shallow water harvest by one-seed juniper from intercanopy spaces. Bledsoe and Fowler (1992) document an increasing herbaceous response to decreasing densities of overstory trees and report no significant increases in grass production without a minimum two-thirds overstory thinning. Preliminary greenhouse studies conducted at Bandelier support the benefits oflitter and slash as moderators of soil moisture and temperature; growth performance of blue gramma seedlings was significantly USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 90 Figure 1-Comparisons of the primary, overstory reduction and slash mulching treatment (n =15) to control (n =3) using four cover components measured at Frijoles Mesa (Graphs A and C) and Garcia Mesa (Graphs B and D). The clustered bars represent three years of measurements: 1994 (pre-treatment), 1996 (two years post-treatment), and 1997 (three years post-treatment). Graphs A and B compare treatment effects on exposed soil and total herbaceous cover across both sites. Graphs C and D compare the forb and grass response between control and primary treatment plots for each site. The standard error bars are times one standard error. 80 70 60 ~ ... 50 > 40 CII 0 0 30 20 10 0 80 70 ~ ... CII > 60 50 0 0 :, 40 30 20 10 ~.------------,-------------------------------~ 0 Control Treatment Control Treatment 9r-----------L-------~------~--------+_----~ Total Herbaceous Cover Exposed Soil ~r-H!H------_4~------i~M------~tH-----~miH----~ ~ 70 Frijoles Mesa ~ 30 o C (J 60 20 50 10 C ... 40 CII > 0 0 30 20 0 60 50 ~ ... CII > 0 Grass Grama Sl SIS Figure 2-Comparisons of total grass cover among secondary, soil surface preparation and seeding treatment combinations, for each year of measurement, and relative to one of the seeded species, blue grama (Bogr). Treatment codes: S = Slash only; SI = Slash Mulch + Imprinting; SIS = Slash Mulch + Imprinting + Seeding; SRS =Slash Mulch + Raking + Seeding. Standard error bars are times one standard error. 10 Garcia Mesa Grass Grama 40 30 0 20 10 0 Control Treatment Forbs Control Treatment Grasses USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 297 enhanced by litter and! or slash mulching treatments (Snyderman and Jacobs, 1995). Watershed level restoration studies underway at Bandelier National Monument are attempting to correlate the herbaceous response to overstory reduction and slash mulching treatment with soil moisture and soil erosion. We suggest that tree overstory removal reduces competition for limited water and nutrient resources while the scattered slash provides benefits to exposed soils: reducing runoff and sediment transport, increasing infiltration and soil moisture, moderating soil temperature, freeze-thaw and evaporation, redistributing nutrients, and mitigating grazing impacts. Combined, these effects create favorable microsites for increased productivity of remnant herbaceous plants as well as for germination, establishment and growth of new individuals from seed. High seed loss in secondary treatments, from some combination of predation and mortality, was evident at both sites based on seedbank analysis at one, three, and twelve weeks post-seeding (J acobs and Snyderman, 1995). Marginal planting techniques, which did not effectively provide seed with good soil contact, combined with uneven precipitation patterns may have been responsible. Slash mulch was observed to be effective in keeping wind and rain from transporting broadcast seed off ofindividual plots. Intense seed predation by harvester ants was observed at the Frijoles Mesa site, beginning soon after application and continuing until effective rain either concealed seeds or stimulated germination several weeks later. Surprisingly, loss of seed was also high at the Garcia Mesa site, despite the apparent absence of harvester ants and occurrence of effective precipitation within several days of planting. Acknowledgments _ _ _ _ _ __ We would like to thank the eighteen Student Conservation Assistants who supported this study through their cumulative seventy-six months pffield work over a four year period. David Snyderman, Craig Allen and Sam Loftin provided valuable technical assistance. This study received financial support from the Challenge Cost Share Program of the National Park Service, the Friends of Bandelier, the Student Conservation Association, and Bandelier National Monument. References -----------------Allen, C. D. 1989. Changes in the landscapes of the Jemez Mountains. Ph.D. dissertation, Univ. of Calif, Berkeley, CA Arnold, J. F. and Schroeder, W. L. 1955. Juniper control increases forage production on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station Paper No. 18, Fort Collins, CO. 298 Bledsoe, F. N. and Fowler, J. M. 1992. Economic evaluation of the forage-fiber response to pinyon-juniper thinning. New Mexico State University Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 753, Las Cruces, NM. Breshears, D. D., Myers, O. B., Johnson, S. R, Meyer, C. W. and Martens, S. N. 1997. Differential use of spatially heterogeneous soil moisture by two semiarid woody species: Pinus edulis and Juniperus monosperma. J. Ecology. 85:289-299. Chong, G. W. 1994. Recommendations to improve revegetation success in a pinyon-juniper woodland in New Mexico: a hierarchial approach. M.S. thesis, Univ. of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. Chong, G. W. 1992. Seventeen years of grazer exclusion on three sites in pinyon-juniper woodland at Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico. Unpublished report, Bandelier National Monument, Los Alamos, NM. Davenport, D. W. 1997. Soil survey of three watersheds on South Mesa. Unpublished report, Bandelier National Monument, Los Alamos, NM. Davenport, D. W., Wilcox, B. P. and Breshears, D. D. 1996. Soil morphology of canopy and intercanopy sites in a pinon-juniper woodland. Soil Sci. Soc. J. 60:1881-187. Gottfried, G. J., Swetnam, T. J., Allen, C. D., Betancourt, J. L. and Chung-MacCoubrey,A L.1995, Pinyon-juniper woodlands, Chapter 6, in: Ecology, diversity and sustainability of the middle Rio Grande basin, Finch, D. M. and Tainter, J. A, eds., USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, General Technical Report, RM-268. Jacobs, B. F. and Snyderman, D. 1995. Restoration Studies. Unpublished report, Bandelier National Monument, Los Alamos, NM. Loftin, S. R 1998. Initial response of soil and understory vegetation to a simulated fuelwood cut of a pinyon-juniper woodland in the Santa Fe National Forest. In: Monsen, S. B., Stevens, R, Tausch, R J., Miller, R and Goodrich, S., eds. Proceedings: ecology and management of pinyon-juniper communities within the interior west. 1997 Sept. 15-18, Provo, UT. USDA, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, General Technical Report INT-OOO. Ogden, UT. Mozzillo, E. 0., in preparation, Management summary of the Bandelier archeological survey. Unpublished report, Bandelier National Monument, Los Alamos, NM. Sydoriak, C., ed. 1995. Resources management plan. Unpublished report, Bandelier National Monument, Los Alamos, NM. Touchan, R, Allen, C. D. and Swetnam, T. W. 1994. Fire history and climatic patterns in Ponderosa pine and mixed-conifer forests of the Jemez Mountains, northern New Mexico. In: Fire effects in southwestern forests, Proceedings of the second La Mesa Fire symposium. USDA, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, General Technical Report, RM-286. Wilcox, B. P., and Breshears, D. D. 1995. Hydrology and ecology of pinyon-juniper woodlands: conceptual framework and field studies. In: Desired future conditions for pinon-juniper ecosystems, 1994 August 8-12, Flagstaff, AZ: USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, General Technical Report, RM-258. Wilcox, B. P., Newman, B. D., Allen, C. D., Reid, K. D., Brandes, D., Pitlick, J. and Davenport, D. W. 1996a. Runoff and erosion on the Pajarito Plateau: Observations from the field. New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook, 47th Field Conference, Jemez Mountain Region, Los Alamos, NM. Wilcox, B. P., Pitlick, J., Allen, C. D., and Davenport, D. W. 1996b. Runoff and erosion from a ra pidly eroding pinyon -j uni per hillslope. In: Advances in Hillslope Processes. Vol. 1. eds: M.G. Anderson and S.M. Brooks. John Wiley and Sons LTD. USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999