Habitat Relationships of Amphibians and Reptiles in the Inyo-White Mountains,

This file was created by scanning the printed publication.

Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain.

Habitat Relationships of Amphibians and

Reptiles in the Inyo-White Mountains,

California and Nevada

Michael L. Morrison

Linnea S. Hall

Abstract-The distribution and abundance of he rpetofa una was documented in the Inyo and White mountain ranges of Inyo and

Mono counties, eastern California. Fourspecies of amphibians and

26 species of reptiles were located in pinyon-juniper (Pinus

monophylla-Juniperus osteosperma) woodland. Thirteen of the 26 reptile species recorded were snakes; the distribution of most snakes remains poorly understood. The concentration of skinks

(Eumeces spp.) at springs identified the importance of wet areas for these species. Results indicated the generally unrecognized diversity of herpetofauna present in pinyon-juniper woodlands, and highlight specific research and management needs.

The Inyo and White mountains are the predominant ranges on the western border of the Great Basin. Because of their proximity to the Sierra Nevada, the Inyo-White mountains would be expected to harbor a larger diversity of fauna than found in more easterly, interior ranges. However, this diversity remains virtually undescribed; there have been few surveys of the fauna in the Inyo-White mountains, and research in the pinyon-juniper

(Pinus monophylla-J uniperus osteosperma)

zone is especially lacking. For example, only a few studies have documented the distribution and habitat affinities of amphibians and reptiles in these ranges (Papenfuss 1986; Macey and Papenfuss

1991a,b). Better quantificati9n of fauna in these areas is necessary before resource professionals can develop comprehensive and inclusive management plans.

The goal of our 6 year study was to document the distribution, abundance, and habitat affinities of amphibians and reptiles (herpetofauna) in the pinyon-juniper zone of the Inyo-White mountains, eastern California and western

Nevada. For this paper, we have also included results from the poorly studied, upper elevation bristlecone pine-limber pine

(Pill

llS

longaeua-P. flexilis)

forest zone.

Study Area

The Inyo-White mountains rise from 1,515 to 4,245 m elevation and are east of, and run parallel to, the Sierra

In: Monsen, Stephen B.; Stevens, Richard, comps. 1999. Proceedings: ecology and management of pinyon-juniper communities within the Interior

West; 1997 September 15-18; Provo, UT. Proc. RMRS-P-9. Ogden, UT: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research

Station.

Michael 1. Morrison is Adjunct Professor, and Linnea S. Hall is Assistant

Professor, Wildlife Biology, Department of Biological Sciences, California

State University, Sacramento, CA 95819.

Nevada Mountains. The pinyon-juniper woodland predominates both ranges between about 1,800 and 2,900 m elevation, and is characterized by an increasing concentration of pinyon, and decreasing amount of juniper, with increased elevation. The shrub layer is sparse and composed primarily of sagebrush

(Artemesia tridentata)

and bitterbrush

(Purshia glandulosa

and

P. tridentata),

intermixed with

Mormon tea

(Ephedra viridis),

rabbitbrush

(Chrysothamnus nauseosus

and C.

viscidiflorus),

cactus

(Opuntia

and

Echinocereus

spp.), and other, less common grasses and herbaceous plants.

The bristlecone pine-limber pine forest begins at the upper edge of the pinon-juniper woodland and extends up to about 3,500 m. It is composed of varying mixtures of the two pine species, with a sparse understory composed of sagebrush and mountain mahogany

(Cercocarpus ledifolius).

There are very few large meadows; the largest riparian! meadow location, Cottonwood Basin, is located in the White

Mountains (at 3,300 m), and is characterized by linear stretches of aspen

(Populus tremuloides)

and willow

(Salix

spp.), but little cottonwood

(Populus

sp.). A thorough description of the environment and flora of these ranges was given by Powell and Klieforth (1991) and Spira (1991), res pecti vely.

Methods

We determined the distribution of herpetofauna throughout the ranges by searching the literature, museum specimen records, field notes of previous workers, and by conducting our own surveys.

We examined all specimen records through 1988 in the

Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ; University of Calif ornia, Berkeley) and the Los Angeles County Natural History

Museum (LACNHM).

We examined and summarized the field notes of expeditions conducted by teams from the Museum of Vertebrate

Zoology in spring and summer 1917,1942, and 1954. Notes from smaller and shorter-term field trips were also examined.

The only comprehensive summary ofthe herpetofauna of these ranges was by Papenfuss (1986) and Papenfuss and

Macey (1991a,b), who visited the ranges, and also summarized literature and museum records. They conducted sampling transects across the southern Inyo Mountains, across

Westgard Pass (central in the ranges), and in the northern

White Mountains.

USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 233

Landscape Distribution

The major east-west, paved travel route across the ranges is State Highway 168. This road crosses the central part of the ranges at Westgard Pass (2,100 m elevation). We drove this road to search for living or road-killed animals from the lower edge ofthe pinyon-juniper vegetation on the east and west sides of Westgard Pass, a total distance of about

15 km. At least 500 trips were made during daylight hours between May and September, 1987-1992.

The major north-south road in the ranges is the White

Mountain Road, which begins at Westgard Pass and runs north to near the summit of White Mountain Peak. We drove this road from Westgard Pass up to 3,100 m in the bristlecone pine-limber pine zone, a total distance of about

20 km, on at least 200 occasions during daylight, May-

September 1987-1992.

Records of all anecdotal observations of herpetofauna were also made during our studies of general vertebrate natural history in the ranges, which spanned a total of 30 months in 1987-1992, or about 75 person-months of effort.

Macrohabitat Relationships

We established both short- and long-term pitfall trapping grids. Short-term grids were placed as follows: (1) Montenegro

Springs, southern White Mountains (T7S, R34E, sec. 36), opened for 1,872 trap days in June-August 1989; (2) Little

Cowhorn Valley, central lnyo Mountains (T9S, R36E, sec. 15), opened for 2,337 trap days in June-August 1991; and

(3) Waucoba Pass, central lnyo Mountains (T9S, R36E, sec.

28), opened for 1,189 trap days in July-August 1991.

We established three longer-term pitfall grids (T7S, R35E, sec. 30-32) to intensively sample the pinyon-juniper zone.

Each grid was 4 ha in size. Thirty-six pitfalls were placed at about 25 m intervals on each grid. Pitfalls were constructed of two number 10 cans as described by Corn (1994); small holes were punched in the bottom of each can to allow water to drain. Each pitfall was covered by a raised wooden lid; no drift fences were used. Pitfalls were run as live traps and were checked at least every 2 days from late May to early

September, 1989-1991, for a total of about 5,300 trap days per grid per year (48,000 total trap days for the study). Each capture was identified, the sex and age determined, and one toe was clipped to identify recaptures.

Habitat Analyses

We quantified the habitat attributes ofthe herpetofauna on the three long-term pitfall grids by establishing 20 m radius plots centered on each pitfall location. Within each plot we measured tree density; the cover of shrubs, grasses and herbaceous species; and cover of rocks and downed material using point-intercepts bisecting the plot.

Results

------------------------------------

Distribution at the Landscape Scale

A total of four species of amphibians and 26 species of reptiles have been observed in the pinyon-juniper zone of the lnyo-White mountains (table 1). The western toad

(scientific names in table 1), black toad, and northern leopard frog are extremely restricted in distribution and are only found in a few springs and ponds. The lnyo

Mountains salamander is the only verified salamander species in these ranges; the salamander occurs in many springs and seeps in the southern lnyo Mountains. There are, however, several anecdotal records of an unknown salamander species made by reliable observers at high elevations in the northern White Mountains (table 1).

Thirteen of the 26 reptile species recorded in the pinyonjuniper zone were snakes. The speckled rattlesnake and striped whipsnake were the only snakes seen commonly throughout the zone (personal observation). We apparently made the first identification of a Nevada shovel-nosed snake, and extended the elevational range of the gopher snake (to 3,300 m) into the Cottonwood Basin, White

Mountains. Additionally, we made an observation of the western rattlesnake that extended the known range ofthis species south in the White Mountains to near Westgard

Pass (table 1).

Eight of the reptile species occurred only at the lower edges ofthe pinyon-juniper zone, whereas the remaining 15 species were found throughout the zone. The eight species at the lower edge ofthe woodland are principally associated with lower elevation (desert scrub) vegetation and apparently barely reach into the pinyon-juniper zone.

Seven species, all reptiles, extended up into the bristlecone pine-limber pine vegetation zone; no verified species was unique to the latter zone (table 1). The only exception found to date could be the possible salamander discussed above. Most species occurred only into the lower edge of the bristlecone pine-limber pine zone, with the exceptions of the sagebrush lizard, western fence lizard, and perhaps the side-blotched lizard.

Macey and Papenfuss (1991a,b) reported observations of two amphibian, three lizard, and five snake species in the pinyon-juniper zone of the lnyo and White mountains that we did not observe (table 1).

Macrohabitat Relationships

Short-term pitfall trapping did not locate any new species nor extend the range of any known species. Sagebrush lizards and western fence lizards were captured at Little

Cowhorn Valley (n = 12 sagebrush and 7 fence lizards); only fence lizards (n = 8) were captured at Waucoba Pass; and both Gilbert en

= 2) and western (n = 4) skinks were captured at Montenegro Springs.

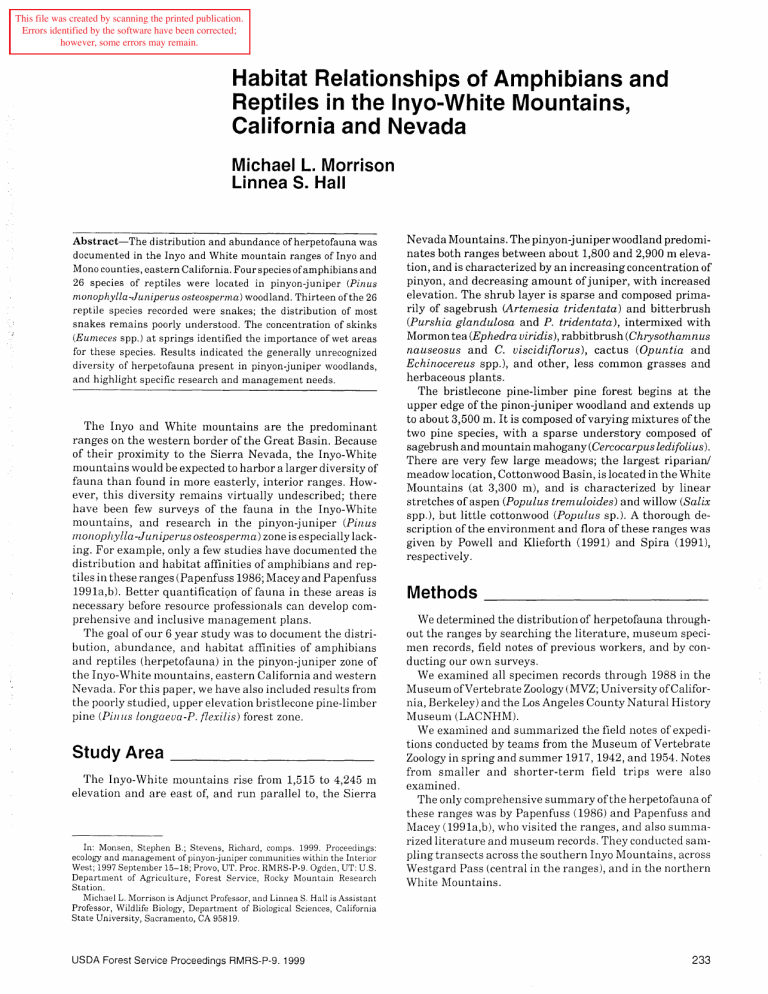

We captured a total of seven species on our three permanent trapping grids between 1989-1991 (table 2). Overall, the sagebrush lizard was the most numerous species captured, accounting for 51.3 percent of all captures. The western fence lizard (31.7 percent) was the only other species that accounted for >10 percent of total captures.

The side-blotched lizard was captured regularly but accounted for only 8.9 percent of all captures. The western whiptail was captured regularly (4.2 percent) but only on one grid ("Westgard"). The western skink (2.1 percent) and

Gilbert skink (1.8 percent) were captured infrequently but occurred on all three grids. The desert night lizard CO.1 percent) was captured only on one grid ("Pinyon") (table 2).

234 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999

Table 1-Summary of distribution of amphibians and reptiles from the Inyo and White mountains, California and Nevada. M&P refers to Macey

Batrachoseps campi [I nyo Mountains salamander]

M&P and Marlow et al. (1979) summarized the numerous records of this relictual species in the Inyos; not recorded from the Whites. Papenfuss (1986) stated that there were reliable reports of salamanders (species unknown) from above 3,000 m in the Whites. We did not locate at new locations.

Bufo boreas [Western toad]

M&P stated has been found above 2,100 m in northern Whites.

We observed what were likely toad tadpoles in a seasonal waterhole north of Montgomery Pass, northern Whites.

Bufo exsul [Black toad]

M&P noted introduced to Batchelder (Toll House) Spring but may be extinct there. We thoroughly searched this spring throughout our study and located no amphibians.

Rana pipiens [Northern leopard frog]

M&P reported from 2,300 m on east side of Whites below

Boundary Peak. We did not locate at other sites.

Cnemidophorus tigris [Western whiptail]

M&P reported to 2,300 m in both ranges. We saw to 2,500 m throughout Inyos.

Xantusia vigilis [Desert night lizard]

M&P reported to at least 2,100 m in the southern Inyos north to the

Mono County line. We found near Westgard Pass at 2,250 m.

Phrynosoma platyrhinos [Desert horned lizard]

M&P reported to about 2,300 m in both ranges. We had no observations.

Cole onyx variegatus [Western banded gecko]

M&P stated the northernmost locality as Westgard Pass, but we found no references for specimens or sighting above about

1,700 m.

Gerrhonotus panamintinus [Panamint alligator lizard]

M&P reported as both ranges below 2,300 m. We saw one dead on the road at 2,200 m near Westgard Pass.

Eumeces gilberti [Gilbert skink]

M&P reported as present to 2,700 min Inyos north to Silver

Creek and Wyman canyons. We captured both this species and the western skink (see below) at the same localities near

Westgard Pass.

Eumeces skiltonianus [Western skink]

M&P called this a high elevation species not found below 2,300 m and may occur to 3,300 m. They had only a single record of the western skink from the ranges. We captured numerous individuals in pitfalls near Westgard Pass.

Crotaphytus insularis bicinctores [Great Basin collared lizard]

M&P reported as throughout ranges to lower extent of the pinyon-juniper woodland. However, museum specimens indicate occurrence to 2,300 m in Silver Canyon. We also found road specimens at 2,200 m near Westgard Pass, and Williamson

(1954, field notes) reported from 2,200 m in Wyman Canyon.

Gambelia wislizenii [Long-nosed leopard lizard]

M&P reported as throughout the ranges below 2,300 m. We made no observations.

Sceloporus graciosus [Sagebrush lizard]

M&P reported below about 3,000 m. We captured several individuals at 3,300 m in Cottonwood Basin, White Mountains.

Sceloporus magister [Desert spiny lizard]

M&P reported below 2,300 m in both ranges. We observed at

2,300 m at Westgard Pass.

Sceloporus occidentalis [Western fence lizard]

M&P reported up to 3,000 m. We captured numerous individuals up to this elevation.

Uta stansburiana [Side-blotched lizard]

M&P reported throughout the ranges below 2,600 m. There are, however, museum specimens from 3,000 m at the Shulman

Grove, White Mountains. We saw active ones near Westgard

Pass as late as mid-November.

Thamnophis elegans [Western terrestrial garter snake]

M&P reported as occurring near streams on eastern slopes of

Whites to at least 2,700 m. We also observed 1 in pinyon-juniper near Westgard Pass, which was at least 2 km from permanent water.

Crotalus mitchelli [Speckled rattlesnake]

M&P reported throughout ranges to 3,000 m. We observed infrequently in pinyon-juniper between 2,000-3,000 m.

Crotalus viridis [Western rattlesnake]

M&P stated range as northwestern slopes of Whites only.

However, we found an adult at Montenegro Spring (2,100 m), which extends the range of this species south to near Westgard

Pass.

Hypsiglena torquata [Night snake]

M&P reported as throughout the ranges below 2,300 m. We had no observations.

Lampropeltis getulus [Common kingsnake]

M&P reported as throughout the ranges below 2,300 m. We had no observations.

Masticophis flagellum [Coachwhip]

M&P reported as entire region below about 2,000 m. We had no observations.

Mastocophis taeniatus [Striped whipsnake]

M&P reported as entire region from 1,500 to 2,750 m. We observed them fairly frequently and found a road kill on 6

December at 2,300 m near Westgard Pass.

Pituophis melanoleucus [Gopher snake]

M&P reported as throughout ranges below 2,600 m. We captured several in Cottonwood Basin, White Mountains, at

3,200 m.

Rhinocheilus lecontei [Long-nosed snake]

M&P described as throughout the ranges below 2,000 m; we did not locate any individuals in the pinyon-juniper zone.

Salvadora hexalepis [Western patch-nosed snake]

M&P described as throughout the ranges below 2,100 m. We collected a road kill near Westgard Pass (2,300 m).

Sonora semiannulata [Ground snake]

M&P stated as presumed to occur throughout the White-Inyo mountains region below 2,000 m. We did not locate during any of our surveys.

Tantilla hobartsmithi [Southwestern black-headed snake]

M&P stated as occurring on western slopes of Inyos. We did not locate.

Chionactis occipitalis talpina [Nevada shovel-nosed snake]

We recovered 2 road kills near Westgard Pass during 1991: 3

June at 2,100 m and 18 June at 2,000 m; these are apparently the first records of this species for these ranges.

USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999

235

Table 2-Relative abundance of herpetofauna on three long-term pitfall grids, Inyo and White mountains, California, 1989-1991.

Species Pinyon Cedar Westgard Total

--.. _-----Number (percent) on grids - - - - - - - - - -

5 (1.1 )

5 (1.1 )

195 (43.4)

11 (3.7)

15 (5.0)

169 (56.1)

11 (2.1)

3 (0.6)

284 (55.4)

27 (2.1 )

23 (1.8)

648 (51.3)

Gilbert skink

Western skink

Sagebrush lizard

Western fence lizard

Side-blotched lizard

Western whiptail

Total

196 (43.7)

48 (10.7)

0

449

93 (30.9) 111 (21.6)

13 (4.3)

0

301

51 (9.9)

53 (10.3)

513

400 (31.7)

112 (8.9)

53 (4.2)

1263

Table 3-Description of three long-term pitfall grids used in the Inyo and White mountains, California, 1989-1991. For variables with P < 0.05 (analysis of variance). mean values that are significantly different are denoted by different capital letters (n = 41 plots/grid).

Variable

Pin~on x

SO

Tree density (no'/ha)

Pinyon

Juniper

Total

Cover (percent)

Shrubs

Herbs

Down wood

Rock

40A

7A

47B

4

2

1

14AB

27.4

12.2

30.1

4.7

2.8

1.2

4.6

Cedar x

SO

63B 31.7

2A 3.8

65A 31.9

5

1

1

16A

5.3

1.8

1.6

5.0

Westgard x

SO

24C

36B

60A

3

1

1

18B

16.2

16.7

21.1

2.7

2.0

1.4

7.2 p

<0.01

<0.01

0.01

0.24

0.59

0.49

0.05

The highest abundance of sagebrush lizards was on the

Westgard grid, whereas the Pinyon grid had the highest abundance of fence lizards. Westgard and Pinyon had substantially more side-blotched lizards than did the third grid ("Cedar").

The three grids differed significantly in the density of pinyon trees, although the Westgard grid was much lower in density than the other two grids. In contrast, Westgard had a significantly higher density of juniper trees than either of the other two grids (table 3). The cover of other plants and substrates was similar among sites.

Discussion

-------------------------------

Our landscape-level surveys of the ranges, when combined with previous field surveys, highlighted the diversity of he rpetofa una in the pinyon-juniper woodland. Although the herpetofauna was predominated by sagebrush and western fence lizards, numerous other species of lizards and snakes resided in the woodland. Toads and frogs were extremely restricted in their distribution, being found primarily in wet locations in the northern White Mountains.

Anecdotal sightings indicated that an unidentified species of salamander may exist at high elevations in the White

Mountains. These records, in addition to the apparent affinity of skinks for wet areas, indicate that future

236 sampling efforts should be concentrated in and around springs throughout the ranges.

We also identified the presence of many species of small snakes. However, neither our survey efforts nor those conducted previously (that is, Papenfuss 1986; Macey and

Papenfuss 1991a,b; unpublished field notes) were of adequate intensity to clarify the range-wide distribution, abundance, and specific habitat affinities of these species.

Our short-term pitfall trapping did not yield any new species nor extend the previously known ranges of any species. Results from Montenegro Springs did, however, exemplify both the co-occurrence of the western skink and

Gilbert skink, and an apparent affinity of these species for wet areas. Although both species of skink were found away from springs in pinyon-juniper woodland, they reached their greatest abundances near the spring. It appears that wet areas (that is, springs, seeps) may function as highquality habitat for skinks.

Our longer-term pitfall grids identified the primary herpetofauna of the pinyon-juniper woodland as one predominated by sagebrush and western fence lizards, with a regular occurrence (but at much lower abundance) of sideblotched lizards and Gilbert and western skinks. Whiptails were added to the community only on the Westgard grid.

Westgard had the lowest density of pinyon trees, but a much higher density of juniper trees compared to the other

USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999

two grids. The Westgard grid had a southern aspect, whereas the other two grids were oriented primarily westward. The presence of juniper and drier conditions on Westgard probably led to the higher overall abundance of animals and presence of whip tails on the grid.

Night lizards were only captured on the Pinyon grid.

Cursory surveys of the grid located additional adult night lizards under thin horizontal rock slabs. Thus, it appears that night lizards may be more abundant than indicated by the pitfall data, with their occurrence restricted to specific microsites.

In summary, we refined the distributional records for many species, including the identification of several new records for the mountains as a whole, and the pinyonjuniper zone specifically. Our results demonstrate the generally unrecognized diversity of herpetofauna present in the pinyon-juniper woodland, and highlight specific research and management needs that could lead to conservation of these species into the future.

We thank H. Welsh, A. Lind, A. Kuenzi, J. Keane, P.

Aigner, L. Nordstrom, L. Baker, J. Block, and L. Ellison for field assistance; and E. Phillips and D. Trydahl at the White

Mountain Research Station (WMRS), in Bishop, California, for logistical support. Funding was provided through WMRS and

V.C.

Graduate fellowships to LSH.

References

--------------------------------

Corn, P. S. 1994. Straight-line drift fences and pitfall traps. In:

Heyer, W. R. and others, eds. Measuring and monitoring biological diversity. Standard methods for amphibians. Washington,

D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press: 109-117.

Macey, J. R.; Papenfuss, T. J. 1991a. Amphibians. In: Hall, C. A.

Jr., ed. Natural History of the White-Inyo range, eastern California. Berkeley, CA: California Natural History Guide 55,

University of California Press: 277-290.

Macey, J. R; Papenfuss, T. J. 1991b. Reptiles. In: Hall, C. A. Jr., ed. Natural History of the White-Inyo range) eastern California.

Berkeley, CA: California Natural History Guide 55, University of California Press: 291-360

Marlow, R W.; Brode, J. M.; Wake, D. B. 1979. A new salamander, genus Batrachoseps, from the Inyo Mountains of California, with a discussion of relationships in the genus. Natural History

Museum, Los Angeles County Contribution to Science 308:1-17.

Papenfuss, T. J. 1986. Amphibian and reptile diversity along elevational transects in the White-Inyo range. In: Hall, C. A. Jr.;

Young, D. J., eds. Natural history of the White-Inyo range, eastern California and western Nevada, and high altitude physiology. Bishop, CA: White Mountain Research Station Symposium, vol. 1: 129-136.

Powell, D. R; Klieforth, H. E. 1991. Weather and climate. In: Hall,

C. A. Jr., ed. Natural History of the White-Inyo range, eastern

California. Berkeley, CA: California Natural History Guide 55,

Univ. of California Press: 3-26.

Spira, T. P. 1991. Plant zones. In: Hall, C. A. Jr., ed. Natural

History of the White-Inyo range, eastern California. Berkeley,

CA: California Natural History Guide 55, Univ. of California

Press: 77-107.

USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-9. 1999 237