Document 11871765

advertisement

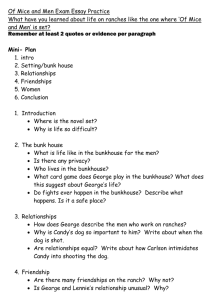

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Being a Sticker Dan Dagget, as presented by Luther Propst1 .···.·... When folk singer Joanie Mitchell sang about paving paradise to put up a parking lot, she warned that: 11You don't know what you've got till it's gone ... Well, ... what have we got when a ranch is gone? Or better yet, what haven't we got? Maybe the only way we can really know what a ranch provided while it was alive is to discover what we've lost after it's gone. Perhaps that's how we can make something positive out of the turmoil we're seeing in the American West today, where in Colorado alone an acre of agricultural land is converted to some other use every 4 minutes. Maybe it's worth it to lose a few ranches if that's what it takes to discover how they enrich our lives, our culture and our environment; or if thats what it takes to convince us that we need to work to sustain the ones that are left. Anyone who's bothered to think about it knows that pressures threatening ranches are growing and will continue to do so. Baby Boomers are coming to the West in droves, tantalized by a media that uses western landscapes to sell everything from pickups to preservation. Fleeing cities that are becoming uninhabitable; freed by the information superhighway from having to live where their jobs are, this new wave of modem sod-busters is coming West convinced that their destiny is manifest and that the ranching culture they are replacing is a liability and a relic. In this scenario is it any surprise that ranches are dying? So, what do we lose when a ranch dies? The most obvious answer is that we lose some of the wide open spaces, the broad panoramas, the pure, uncluttered sweep of nature that defines the American West. And in its place we're left with sprawling suburbs and strips of fast food joints. And that's just the beginning. We lose the viability of the agricultural economy that enables rural communities to resist the seduction of suburbanization; that serves as an essential element of the sense of place and neighborliness that cause the residents of those communities to want to stay there and inspire so many of the rest of us want to move to them. When a ranch dies nature loses too. While pronghorn, sage grouse and even mountain lions and wolves can find the pure grasslands, unfragmented stands of sagebrush, and expansive areas of undisturbed landscape they require on well-managed ranches, subdivisions can fragment and destroy the viability of the very habitats that are essential for these animals' existence. For people who have lived and worked, even been born on a ranch, its loss is a personal tragedy the rest of us can, at best, only partially understand. Frequently, this loss occurs when a family member dies without an estate tax plan and the family discovers that they owe the government more than half the value of a large piece of property assessed as a potential high-end development. More often than not the only way to pay that bill is to sell the ranch. Personal loss, the loss of the West's wide open spaces, of some of its most productive wildlife habitat, of its cultural diversity and sense of place; the loss of viability of agricultural economies and the destabilization of the rural communities they support-this is some of what we lose when a ranch dies. But the greatest tragedy is that many of these deaths could be avoided; avoided easily enough that it's fair to say that some ranches die of plain, ordinary negligence, Some, it could be said, come pretty close to committing suicide. It's no news that ranches have been going belly up for as long as there have been ranches. They've been going bankrupt, been gobbled up by suburban sprawl, been bought out and tossed aside by celebrities, cut up into forties, and turned into wildlife refuges, parks or preserves. And it's 1 The Sonoran Institute, Tucson, AZ. 350 old news (but it's still news) that those who have managed to survive all this are the ones that have been able to change. To switch from longhorns to herefords to Barzonas. To hay the meadows and· rotate their herds. To host a few hunters. To live frugally and learn to be what writer Wallace Stegner called a "sticker." The ranchers who survive in today's West, the stickers, are the ones who are learning to adapt to the changing economics and land-use patterns that unavoidably are shaping the future of the West. They're the ones who are learning to ranch more than livestock; to ranch the view, the ecosystem, the lifestyle, even wilderness. We know it can be done because it's already being done. The ranchers who will be here tomorrow are those who are willing to learn to use all the tools at their disposal: conservation easements, estate planning, conservation development, collaborative planning. Today that's as important as knowing how to use a rope and a good cow horse. (Even more so, but we hate to admit it.) Because these tools are unfamiliar to most ranchers, and because to use them properly requires a high level of expertise, those who are going to be stickers are also going to have to learn to effectively use help from others to get the job done. You've always prided yourself on being independent? Now you're going to have to learn how to be interdependent. Some have already taken the plunge. In many cases they had to. From their successes we can take heart and inspiration. From their failures we can learn what not to do. Ranchers on the Elk River near Steamboat Springs, Colorado--home of one of the fastest growing ski areas in the West--used a tactic more commonly associated with martial arts than with Western politics to keep their ranches alive. Instead of resisting the stampede of boomers threatening to inundate the Elk River Valley with a tidal wave of recreation homes, they redirected the energy of that tide, as an aikido master might redirect the charge of an aggressor. In the process they not only saved their ranches but made them more prosperous. With consulting help from a Denver conservation planner, a couple of pioneering Elk River Valley ranchers marketed a limited number of building sites on their ranches in areas where they would have little or no impact on agricultural operations. Then they placed conservation easements on the undeveloped remainder of their land. By creating homesites that were able to demand top dollar, those ranchers were able to maximize return while developing a minimum amount of land. By applying conservation easements to the rest of their land, they were able to reduce its taxable value sufficiently that when it comes time to pass the ranch on to the next generation, as Colorado rancher T. Wright Dickinson puts it, they won't have to buy it back from the government first. Remedies used to save ranchlands can even involve cows! (Now, there's a novel idea!) That's the case in northern Arizona, where an internationally known artist bought a ranch that encompasses 106,000 acres of private, state and Forest Service land surrounding a landscapesized art project that's attracting worldwide attention. The artist/rancher is applying the profits of a cow-calf operation rejuvenated by holistic management practices to buy back some of the 500 forty-acre parcels that were created when part of the ranch was subdivided about thirty years ago. Just four years into the rejuvenation the cows are buying their first five forties, and in holders who threatened to shoot the rancher's cows when he first started up are now offering to kiss them. As good as these stories sound, they are in some ways a distortion. Some of the ranchers applying these remedies are "deep pocket" ranchers who don't rely on agriculture for their main means of support. Working ranchers scraping to make a living in an unpredictable market and a hostile political climate have proven less likely to grant or even to sell easements on real estate that may be their family's only ace in the hole when the going gets rough. Though it is true that taking chances with your best bet is not something you should do lightly, there is a growing number of ranchers around the West showing that they can succeed in shaping the future of their lands, their families and their communities if they know all the tools in their 351 tool bag, know how to choose the one they need when they need it, and know how to use it after they've chosen it. In the process these people are proving that they are their own best bet. They•re proving that they are stickers. So can you. Note: This article was originally published in Range Magazine, Summer 1996, and was taken from the script of a slideshow presentation written by Dan Dagget for the So no ran Institute of Tucson, Arizona. In addition to the slideshow, the lnstitute•s Ranch Outreach Program offers a Private Land Options Guidebook that highlights successful examples of ranchers in the Rocky Mountain West who have protected their agricultural land base and generated income with flexible conservation strategies, such as limited development and conservation easements programs. This publication also provides estate planning strategies, an annotated bibliography on pertinent articles and books on preserving ranches and open space, and a list of resources and organizations that provide technical assistance on private land conservation. For more information on this program contact: Luther Propst, Executive Director, the Sonoran Institute, 7290 East Broadway, Ste M, Tucson, AZ 85710, (520) 290-0828, fax (520) 290-0969, e-mail soninst@azstarnet.com. 352