Document 11867133

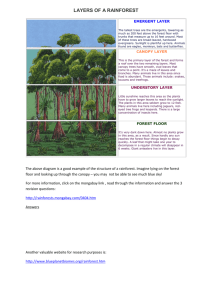

advertisement