.

advertisement

--

~--­

~

I

i

,rl

.

J'

This paper riot to be eited ..\ithout referenee to the authors

International Council for

the Exploitation of the Sea

..

Shellfish cOmrIUttee

C.l\L 19951K:40 Ref: F

The Azorean squid L'!lig() jorbesi (Cephalopoda: Loliginidae) m

captivity: reproductive behaviour

Filipe M. Porteiro. Joao M. Gon~ves. Frooerieo Carcligos & Helen R.

MartinS

Departarnento de Oceanognma e PescaS da Universidade dos A~ores. PT 9900 Hortl

Abstract

Reproductive beha\iour of L. förbesi in captivity iS described. Male·riiate agonistic internctions

increaS'ed when a female is introduced between triaIes. Mate pair formation is quickly established with

acorisequent hier.irchy of dominance bet\veen males. During such beha\iour the male coristrained the

female againstthe tank wall. isolating her from theother maIe present Exchange of the partnerS

in~olved in courtship was fe,,, times observed. A chromatic pattern associated with courtship was

diSi>layed continuously by the dominant male. Thfee females laid eggs on the tank PVC walls. One of

them SUI'\ived 12 days after spanning. Tbe reproductive orgails of post·spa,..ning feInales bad mature.

m:uuring :md immature oOc)1e. Spa,..ning b7haviour :ind :i briefdescnption of the si:iaWn is presented.

An update ofthe components ofbeba..iour is provided.

Introduction

Squid ai-e schooIing soeial invene1>cites

..\ith

high developed system' of

comniimicacion :uid camouflage. They ure

able to exhibit many ritualised beha\icumI

patterns tbat can be described as a

coinbinatiori of chromatic. postumI and

mcvement componerits (Packard &

Sanders, 1971; Packard and Hcehberg,

1977;

Haßlon.

1982).

Chromatic

componentS, rriade up by seleetive nervous

e~eiciticn of units cf chromatcphores and

iridophores (P~ekard. 1982) are the eore of

the

visual

commumcation

amcng

cephalopods. Body patterns are associated

with specific behaviour as feedirig,

predator avoidarice. courtship. ete. and

they can alter during the omogeny of one

spccies (e.g.• Hanlcn & Woltering, 1989).

The accurate descripticn of the eomponents

of pattemmg is required for several

biologieal approaehes as quantitative

ethOIcgy. b~haviotimI taxcnomy and

phylogem:tic analysis (see Hanlcn. 1988

a

and Hanlon et. al. 1994). However, the

description of tbe behaviour is somewhat

complicate due .to the multiplicity arid

ambivalence of the sigrials combined with

the dependence cf their expression on

extemaJ. environment (Moynihan &

Rodaniche. 1982). Obviously, observations

in the field ure the ideal when this is

possible. but when squid gi-ounds ure

unkno\\n or not accessible. studies in

capti\;ty are an alt~n1ative. Also. the

proximity to the squid and the confuted

space can turn some behavioural patterns

conpiscous.

.

Oetopods and sepiids were the cephalopods

preferred for beha\ioural sriidies, both in

situ and in labor.ltory. Nevertheless, the

behaviours of some myopsid were

extensively investigated (in field e.g.•

:\Ioymhan & Rodaniche. 1982~ Sauer &

Srßale. 1993: Hanlon er al. 1994 and iIi

capcivity e.g.. Hanlon 1982, Anlold, 1990).

Lvligo forhesi is the oilly loliginid species '.

lhing arourid the Azores islands. It inhabits

inshore water from the surfuce. ai night.

--

-

--

----

.,

·"

dO\\n to 400 meters during da)time. A

daylight squid jigging fishery was kno\\n

sinee the last eentury (Drouet, 1858).

Mainly maturing and mature squid are

caught (Martins, 1982). However, the

spa\\ning grounds of this population and

spa\\ning migrations bave never been

deteeted. Naturallaid eggs have been found

only once (porteiro & Martins, 1982) in

the Azares.

The Azorean L. forbesi proved to be

effieient for culture e:<:perirnents, at least

for maintenance and reanng (sensus

Boletzky & Hanlon, 1983). Squid embryos

(laid by captive females) were transported

to Marine Biomedical Institute, Texas arid

two successful reanng. trials were carried"

out (Forsythe et al., 1989; Hanlon et al.,

1989). During maintenance preliminary

studies of adult squid behaviour" were

condueted (Porteiro et al., 1990). There,

17 chromatic, 6 poStural and j movement

components were described as weil as

feeding arid agonistic behaViour. Ho\vever,

reproductive behaviour was not extensively

emphasised.

Presently, we bave a closed sea-water

system designed specifically for squid

culture (see Gon~ves et al., 1995) which

allow to maintairi simultrineously' a

signifieant number oflarge squid.

In this study we present additional

qualitative information of the behaviour of

captive squid mainly related with courtship

and spa\\nmg.

recorded daily and several ..vater

parameters controlled regularly (see

Gon~ves et al. 1995, for a complete

description ofthe system).

The number of squid inside eaeh tank was

variable (1 to 7) and different combinations

of sexes were mamtained (e.g., 1 female

and two males, 2 feIriaIe and 2 lna1es, 1

female"and 4 males, etc.). Individual squid

were· distinguished thrOught natural skin

rilarks cr artificial tags

Observations v."ere performed during day

time, from the top of the tanks and laSted

from 10 minutes to ca. 2 haurs. While

observing, the black plastic cover was

partially elevated and the exterior light held

at minimum to avoid major disturbance.

The water influx was, also, suspended.

Squid were fed once or twice a day.

\\-:lS

Trachurus picturatus, Pagellus bogaraveo

and Scoinber japonicus were the main food

items. Feeding took place in the marning

and atnoon.

The hierarchical oi-ganisation of bemiviouf

as described by PackaCd & Sanders (1971),

Packard & Hochberg (1977), and Hanlon

(1982) arid the behavioUraI components

terminology previously established for"

loliginids (Hanlon, 1982, 1988; Porteiro et

aL, 1990;SaueretaL~ 1992, 1993;Hanlon

al., 1994) were adoptoo.

er

Results

Ari

Material aod :\'Iethods

Several squid were rriainciined during t\Vo

sets of experiments (16 Oetober to 27

December 1994 and 2 February to 18

April). The squid size ranged was between

275 to 639

DML. Squid were eaught

by jigging, tr.l.nsported ashore ::md kept in a

elose sea water system. Basically this

arrangement consist af three circular t:lnks

(3.6 m 0 arid 0.90

high: ca 80001 of

natural sea \\-ater) painted with verrical

dark stripes on the \\-alls and ca. ..lern of

gravel an bartom Light was kept at dim

during all the experiments. temperature

mm

m

average of 7.6 squid were maintained

simultaneously in captiviiy and the avernge

survival waS 17.7 days (up to 46 days) in

the first experiment. During the second

trial the average survival \\-:lS longer (22.8

days) niainly due to the preferential

maintenance of mature, maturing squid

and sexual segregation in same tanks.

Behaviour

.Wale-male ü1teractions

~[ale-male

agamsttc be.'taviour was

observed many times. In the tanks a

hierarchy af domirumce was eSt:lblished.

~crmaIly, the weal<er male die with major

damaged areas after few d::i.ys in captivity

2

1

and successively all squid but the dominant

male die. The most obvious damaged areas

were usually the same: the latero anterior

part of the mantle, funnel and head.

Injuries on ehe fins and on ehe posterior tip

of mantle were caused by abrasion and

collision on the tank walls, respeetively.

Lesions on the anterior dorsal tip of the

mantle were commonly observed but eould

not be related with any type of eontaec.

Agonistie interactions oceured between

male of markedly different sizes are

maintained together and between males of

the same size or of different size when

competing for reproductive dominanee,.

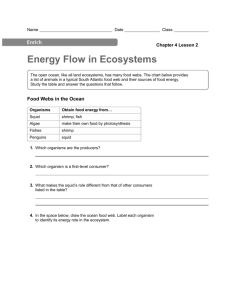

Fig. 1 - Dorsal view of counship body pattern of adult male squid Loligo forbesi in capnvlty.

Composed by the chromatie components, White arm tip. Accentuated tesris and .rlccentuaced digestive

gland.

All the movement eomponents preVlous

deseribed for the speeies (Parallel

posirioning, Fin hearing, Forward rosh,

Chase and Flee) were observed. Some

variation on Forward rosh was reeorded:

the aggressor eharges ehe subordinate male

by jetting against him the tentacles

resulting often in eontaer. TItis component

was preeeded by Chase (by the dominant

male) and culminate with Flee by th~

subordinate male). All dark is the common

body pattern in th se intemctions (Dark

flashing was ::Uso observed several times).

Perpendic:liar

positiomng,

a

new

movement componenr.. was recorded dunng

low stress situations. TItis is characterised

by the presence of several males elose

together moving on different vertic::u levels

mainuining between them perpendicular

positions. The chronie chromatlc pattern

was predominantly observed during such

behaviour (Clear. Dorsal scripe).

lvfaie- emale courtshiv behavlOur (mare

paIr/ormanon

Mature male-femaie inter:lctiv~ benaviour

expressed

by

captlve

squid

was

characterised by Pair formation. When a

female was in a tank with males, one of the

latter would shortly afterwards change his

behaviour.

The male exhibits his

dominance isolating the female from the

other male squid. He constrained her

against the tank wall limiting her

'swimming space. A short distance was

maintained continuously between the two

and prolonged fin to fin contaet occurred.

A circular motion around the tank wall was

prevalent. in opposition to the normal

forward backward radial trajectory.

It was always the male who ~nforced ehe

pair jormation behaviour. However, the

preservation of the eouple depends of the

male aptitude to ;lvoid the evasive action of

the female (unhealthy males are unable to

maincain a pair with a hea1th female).

Sometimes

male

sexual

dominance

exchange was observed (i. e.. , the dominant

male is replaced by another). Also, the

dominant male may change his partner

preference (observed when a new female

was introduced in the tank). Most of ehe

pairs were suble for se'/eral days.

Jockeying J.lld Parrymg (sensus Hanlon et

ai. 1994) were observed several tunes and

often culminated in violent male-male

3

agonistic behaviour (see above). Stress also

inereased in the tank also when a male

interfered with the trajeetory of the pair.

Subordinate squid tend to avoid such

................................

..

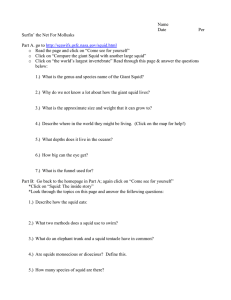

Figure 2.Top plan of the tank and detail of the area selected by squid to lay eggs (see text).

interactions whieh is diffieult given the

eonfined space ofthe tanks.

The courrship behaviour is characterised

by a specific chromatic pattern. That

pattern is more obvious in the male. At

least, three dorsal chromatic components

are ~xpressed to fonn the Courtship body

pattern (Fig. 1): Accentuated testis,

Accentuated digestive gland and White

arm tips. Strong green iridescence on the

dorsal mantle areas was exhibited. During

all watehing periods the dominant male

frequently showed this pattern (it ean

pt:rsist during a long time). However. it

was more conspieuous when another male

was in the proximity of the pair. The

female display was of a less obvious

chromatic pattern. but also some distinet

components were consistently present (e.g..

Don'al stripe. Ivfantle spots, Dark fin

fine). Whlte arm fips (as in males).

Accentuated

ovary,

Accennlated

nidamental oalands and Asvmmetric

ocular

•

spot (on the male side) were also observed

duling

more

intense

interactions.

As....m metrv of the ehromatic eomponems

w~ 5ho~ (stronger on the adjacent squid

side} by the MO parmers.

Spawning behaviour

Three spawns were laid by captive females

during the period of observation (Tablel.).

All squid initiated spawning during

aftemoon and continued through the night.

Two of the females (Al, B2) that started

egg-Iaying, finished one day 1ater and then

died. One female (B 1) lived for 12 days

after spawning. During that period she ate

4 small meals (average daily feeding rate of

2.1 % against 6.5% before spawning). The

female Al bad paired with a dominant

male (two male squid were in the tank) and

B 1 forrned a stable pair with a sole male in

the tank. The squid 82 were all the time

alone.

Sinee light seemed [0 influence behaviour

of the squid, observations of the spawning

process were gready limited by the dark

condition in the tank. However, some

postural and movement components were

observed. The female approached the egg

mass (previously laid) with eonie arms and

when in contact with them she spiayed the

arm tips and attached a new str.lI1d (Esg

holding). This activity took around _0

seconds or less. During this operation the

squid unduiated the fins vigorously in a

forward movement. The body was kejJt

parallel to the substrarum.

4

..

{

am

Frequently,the female sW

fast to theegg

strands handled them and jetted ,water

violently toward the spa\\n in back",..ard

mo\'ement. This beha\iour Y,as observed

manv tirries. Male also made such

be~viour, but less frequently. ThemaIe

was alwavs swimming elose to the fernale,

showing the courtship body pattern ~ith

high iridescence (Mate guarding) .

At least the first strands laid by the squid

were fixed elose to the surfaee on the tank

wallover a PVC liner, (fig.2). The squid

B2 iaid eggs on the same place where the

prrnous strandS were laid by BI. Water

flow WaS at a maxm'l1.uu at spa\\n location

(oxrsen level \Vas, elose to saturation

unifonnly in the tmks). Later some

capsures were disperse and others were in a

burich, throughout the gcivel bottom. Few

of thern were cemented on the basalt

gravel. It was not cIear to wh::ii extent these

strings v,'ere displaced from the PVC wall

by the jenmg and manipulation behaviour

of the female.

Spawn

The spa\\ns were eomposed by well-sh:iped

egg strands (normal strands) and by a few

with redueed dimensions and with fewer

eggs or none (balloon Strands). Fourtythree common strands were laid by both

squid Al arid BI. The squid B2 lay

significandy less (15) of whieh 50% of

them were empty. The remairiderS were

shorter and bad fe\v eggs thanthose from

the other. squid. The norIDal sti':inds. bad

bet\~,een 25 and 90 eggs and the percentage

of fertilisation was 64%.

balloon

strands bad a lower percent:age of

fertilisation.

Reeentlv fixed strings, (during the fust 2-3

houes), • were more siretchilble, thin and

long, but afterwards they decrease in size,

and the gelatinous ninics became more

finii

The.

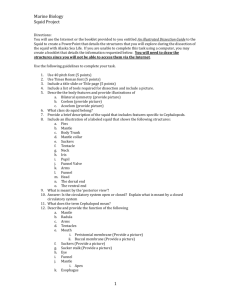

Table 1. Refereneeof L. jorhesi female squid timt spa,\n in captivity. DML, i - I?0rsai man~e i~gth

when captured; BW i-Total body weight when captured; OVW f - Ov:uy welght after spawnmg;

ODPW r- Proximal oviduet weighl after spawning.

.Ref.

Date of

capture

Days

captive

before

Days fram DMLi

sp'a\Vnmg , (nun)

to dead

B\Vi

OVW

(g)

f

f

(g)

(g)

ODPW

spawnimz.

AI

BI

B2

05.11.94

16

09.02.95

03.03.95

8

7

Reproducti....e organs

/emales

0/

1

12

1

31

330

993.0

279

835.0

607.9

33.7

16.8

55.4

56.9

0,8

6.0

post-spawning

Post-spa"ning ferilales still had ~ture,

maturing and immature eggs m the

proxinial oviduct and ovary (see Tabl~ 1)~

All had rnatcd but fe,v sperm were in the

bursa colmlatr:x. The ovary of the fe=nale

BZ lud a high quantity of ocC:.1e c!C:,~ to

rnaturation but less few eggs in the

oviducJ.1 comple::.. The ferI1aIe BI bad i

few hundredS mature eggs in the oviduct

and ooc:-te in v::l.nous devdcpm.:nul .rt::l.ges

in the ovar)'.

Discussion

Agonistic behaviour be:'veen males ~~ ~e

main reason for mortallty both by colliSlon

and abrasion on the tank walls or by direet

charge. This behaviour \vas.obs,erved ,in

several species kept in captiVlty but bodily

contact has oDly been rarely observed (see

Arnold. 1990; Hanlon et al. 1983).

Prcbablv. the coniined space in the tanks

ccmbin~d \\;th the big size ?f the squid

:l2!!1"::l.v::l.te .menistie interactiens ccmpared

t;-animals in

the wild. In the wild the

5

,

,

subordinate squid can run away before

being touched during an attack. These

interactions are more evident when

different sizes male squid are mairitained

together or when males compete for

females

(see Hanlon,

1990). No

cannibalism was recorded probably due to

small differences bet\veen the size of

captive squid.

Pair formation 'was observed for the firsi

time for L. forbesi. HO\vever, it has been

described for several other squid held in

captivity (e.g.• L opaleseens by Hurley,

1977; L. pealei by Amold, 1990; L (D.)

plei by Hanlon, 1981) as weIl as in the

natural

spa\\ning

grounds

(e.g.•

Sepioteuthis sepioidea by Moynihan &

RodaIiiche, 1982; L. v. reynaudii by Sauer

& Smale, 1993). During our observations,

captive pairs seem 10 be quite stable and

male dominant, except when a weak ll1a1e

is not abte to contain the evaSive behaviour

of the female. Tbe latter behaviour can

support the assumption by Hanlon (1994)

that female choice and evaluation of the

partner is an iritPOrtaIlt reproductive

str.:i.tegy bet\veen squid. However, llla1e

dominance has been described by several

authors based on the displacenierit of ari

intruder male by the paired male and the

maintenance of the originill pair. Pair

stability on field is not kno\\n but it

probably split during riight (see Sauer &

Smale. 1993). The long duration of the

pairs obsenoed in this stUdy can be an

arrifice due to thecaptive condition.

Although, we did not observe ccpulation,

we know that sperm is stored only in the

bursa copulatnx (Porteiro & Martins.

1994) which indicate that just head-to-head

mating occurs. Very little sperm was found

in the bursa copularnx of post-spa\Vnmg

females. This suggests that the amount of

sperm in this organ is not enough for

fertilisation if a prolonged spa\\ning period

occur or if one intensive sp:mning is l1lade.

We :lgree with HanIcn (1994) that squid

reprcductive tactics would be better

understood if anaIysed in a sperin

competition contest. The existence of small

mature r"sneaker'') males \"ithin this

spec:es (Martins. 1982: Boyle & Pierce.

as

1994)

weIl as Jockey;ng and Parrying

movernent componenis cari indicate an

alternative reproduCtive str3.tegy, aS

observed for L v. reyruludii (Hanlon et al.

1994). The meclUiriiSiris of sperm

competition are not lciIö,,,n for the majority

of cephalopodS.

Arnold (1990) suggest thai L. pealei pair

formation and consequently reproductive

doininaßce by the Iriale. is established by a

visUa1 Stimulus (i.e.•. the presenee of egg

masses m the aquarium). Hurley (1977)

found some evidence that egg deposition is

visually Stirriulated by the preSence of

preVious spa\Vns but he could not ioelate the

male reproduCtive dominance 10 presence

of eggs. In our case pair formation

occurred without any visua! externaI

stizllulus,

it

eStablished

soon as a

feIriale was mtrOduced among ritales.

Male chromatie eomponents related 10

reprOductive dOßUnance behaviour have not

been deseribed previously for this species.

White arm tips cOuld be associated 10 the

importance .of the arms in rrlating and egg

mass h3ndling. The Accentuated testis is a

component very common arnong 10liginidS

and interpreted as a sign of mature

coridition. Tbe component Accentuated

digestive gland is described hen: for the

tirst time alld it could be a sign related to

theeondition of the squid. since this organ

is used as storage resen'e. Similaicourtship body pattern is not found iri the

literatUre.

Is accepted that acute body patterns

(expressed during few seeondS or minutes)

are more useful for behavioural ta.'conomy

and phylogenetie approaches tfcin chrome

patterns (whieh can be displa):ed during

lang periods). However. courtship body

pattern (as, a chrome pattern) is

stereotyped, species-specific and orie whieh

proVide more information about the species

chafaeteristies (Hanlon, 1988). It would

have ethological interest to compare the

behaviour between Azorean and Europe::m

populations of L. for~esi smce they are

genetically separated (Brierley et al. 1993;

Pierce et aI.• 1994) and body patterns c::m

be used probably as a eharaeter which

shows variations at the population or sub-

as was

as

6

•

.

(

•

species level (Hanlon, 1988; Hanlon et al.

1994). One example of different

reproduetive behaviour benveen these nvo

populations is show in the nurnber of eggs

within each str:md. Lurn-Kong (1993),

reported a mean vaIue of 109 eggs per

string against less than 90 found by us in

several spa\'fns. Also, the percenmge of

mated immature females in Azores seems

to be higher than L. forbesi from elsewhere

(Porteiro & Martins, 1994). In order to

provide basic information for further

ethologic::u companson it is presented an

update of body components recorded for

the Azorean population of L. forbesi

(Table 3).

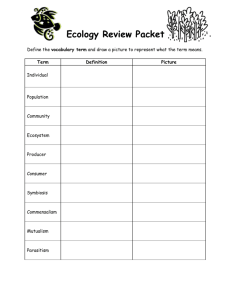

Table 3. Update of the behavioural components recorded for Lo/igo forbesi (based on Hanlon, 1988;

Poneiro et al., 1990; this scudy; and unpublish observations).

Chromatic components:

Dark components:

•

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

'J,,: All

dark

Later::l1 mantle streaks

Ring

Fin and mantle spots

Infraocular spot

Dark fust or third arms

Darkarms

Mid-ventr.ll ridge

Later::l1 mantle stripe

Dark fin line

Mantle margin stripe

Dorsal stripe

Shaded eye

Postur::l1 components:

1.

2.

...

.J.

4.

5.

6.

7.

3.

Two raised arms

DO\mward curling

Extended tentac!es

Splayed arms

Ellipsoidal eyes

Bottom sitting

Egg holding

Perpendicular positioning

Fresh laid egg strings were sirnilar to those

described for L. pealei by Roper (1965)

(leng :md soft). The duration ef softness ef

the string tunics can presumably be rehlted

\"ith the fertilisation process. Tnis

me::..:..:mism remains co be studied.

Variation in the way that squid make their

sp:l\\ning bed is knC\\n (see Vechicne.

1983: Sauer er al. 1992). From our

Light components:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

Clear

Dorsal mantle eollar iridophores

Dorsal iridophores splotches

Gold irideseent sheen

Aceentuated testis

Accentuated nidamental gland

Accentuated ovary

Accentuated digestive gIand

White tip ofarms

Movement eomponents

1.

2.

...

~.

4.

5.

6.

7.

3.

9.

Par::l1lel positioning

Fin beating

Forward rush

Chase

Flee

Inking

Jetting

Jocking and Parrymg

Mate guarding

observations it is difficult to say how this

species makes their spa\'.ns in nature. The

loeation where the squid fi.'ced their eggs in

the tanks is probably related to the water

current or to the existenee of a PVC fold

(see Fig.l). The later supposition. if

correct. can suggest that cre"lices or smaIl

caves are used fcr spa\ming as discussed

before by Porteiro & ~[artins (1992). L.

7

vulgaris in Madeira spa\..n in such bottom

1--

structures (p. Winz. pers. comm.)

Death of captive squid after spa\..ning haS

been recorded by several sttidies and

accepted as a natural behaviour. The

presence of mature, maturing and

immature eggs in the reproduetive system

of post-spa\'.ning females and the survival

of one female for several days (12) after

egg- laying could support the assumption

of a prolonged intermittent spa\..ning

before exfuluStion. Several questions arise

when this problem is examined: v,'hy does

the squid die befoIe all the eggs are laid? is

this ecologically justified? have the "üd

femaIe the same behaviour or is it

influenced. by captive condition? does she

need high food input after spa\..ning one

batch of eggs? This should be investigated

carefully to 6stablish the reproductive

behaviour ofthis loliginid.

a

AcknowledgementS

This work could not be done ",ithout the assistance of Paulo Martins. Thanks to Ricardo S.

Santos, to commentS and revision of the manuscript.

.

This ?''ork was funded by the European Commission within the frame of EC research

programme in the Agriculture and Fisheries seetor(AIR. Contract No. AIR l-CT92-573). We

also thank to the Region::U. Secretariat of Agriculture and Fisheries of the Azores Government

who gave us permission to use their installations at Porto Pim beach (Rorta) and supported its

running costs.

References

Arnold. I. M 1990. Squid mating beruivior. Pp 65-75, in: Squid as Experimental Animals, D.L.

Gilbert, W. I. Adelman Ir &. I. M AInold (Eds). New York. Plenum Press, 516pp

Brierley, A. S. ,. 1. P. Thorpe. M. R.. Clarke &. H. R. Martins, 1993. A preliminary biochemic:ll

genetic investigation of population stnleture of Loligo förbesi Steenstrup. 1856 frOm British Isles

'and the Azores. Pp, 61-69, in: Recent Advances in Cephalopod Fisheries Biology, T. Okutani.

R.K. O'Dor & T. Kubodera.. Eds. Tokai UDiversity Press. Tokyo, Iapan. 752 pp.

Boletzky, S. v. &. R. T. Hanlon., 1983. A review ofthe'laboratory maiIitenance, rearing, and culture

of cephalopod molluses. •\femoirs ofthe .Vational.\luseum ofVictoria. +t:147-187.

Drouet H., 1858. Mollusques manns des lIes Acores. ....Iemoires de la Societe, Academique de I:-lube.

22: 53 p.

.

Forsythe, 1. W. &. R. T. Hanlon. 1989. Gro'\th of the Eastem Atlantic squid. Loligo forbesi

Steenstrup ~follusca: CephaJopoda).Aquac'.llture and Fisheries .\fanagement, 20: 1-14.

Gom;aJves. 1. M.• F. M. Porteiro. F. Cardigos & H. R.Martins, 1995. Adult squid Loligo forhesi

(Cephalopoda: Loliginidae) in c:lptivity: maintenance arid transport International Council for the

Exploitation ofthe Sea. C.M. 19951F:14 Ref. K

Hanlon. R. T., 1981. Courting and rnating beha\ior in the squid Loligo (Doryteuthis) plei (abstract).

International Society oflnvercebrate Reproduction.l p.

Hanlon. R. T., 1982. The functional orgWzation of chrolnatophores and iridiscent cells in the body

patterning of Loligo plei (Cephalopoda: Myopsida). Malacologia, 23(1): 89-119.

Hanion. R. T.. 1988. Beha,ioraJ and body p:iuernig charncters useful in ta.xonomy and field

indentific:luon of cephalopods. .\lalacologia, 29( 1): 247-264.

HanJon. R. T., 1990. Maintenance. reanng, and cUIture ofteuthoid and sepioid squids. pp. 35-62. in:

Squid as Experimental Animals, D.L. Gilbert, W. J. AdeIxii.an Ir &. I. ~l Arnold (Eds ). New

York. Plenum Press. 516 pp.

HanJon. R. T., ·1994. Mating systems of cephalopods: contrasting strategies and the possible

iruluerices of. sperm campetition behu\ior. Programme and AbstraCts of the Napoli CIAC

Symposium "The Behaviuur and .Vatural History of Cephalvpocis" (Vico Equense. 5-11 June.

1~'94): 14.

3

•

•

•

r

•

Hanlon, R. T. ,. R. F. Hixon &. W. H. HulIet. 1983. SU1'\ival. grO\\th and beha\ior of the Ioliginid

squids Lo/igo p/ei. Lo/igo pea/ei and Lo//iguncu/a brevis (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) in closed

water systems. Bi%gica/ Bulletin. 165(3): 637-685.

Haßlon. R. T.•• W. T. Yang. P. E. TUrk, P. G. Lee &. R. F. Hixon. 1989. Laboratory

and

estimated life span of the Eastem Atlantie squid, Lo/igo jorbesi Steenstrup. 1856 (Mollusca:

, C:phalopoda) A.quacu/ture and Fisheries .\lanagement, 20: 15-34.

Hanfon, R. T.•. M J. SffiaIe &. W. H. H. Sauer. 1994. An ethogram ofbody patterning behavior in the

squid Lo/igo vu/garis reynaudii on spa\'i.ning grounds in South Africa. Bi%gica/ Bulletin, 187:

sea

culture

363-372.

,,

,

,

"

,

Hudey, A. C., 1977. Mating behavior of the squid Lo/igo opa/escens. Marine Behaviour and

Physi%gy, 4: 195-203.

,

,

LUni-Kong. A.,1993. Oogenesis. fecundity arid pattern of spaWning in Lo/igo jorbesi (Cephalopoda:

Loliginidae). Ala/ac%gica/ Review, 26: 81-88.

Martins. H. R.. 1982. Biologica1 studies of the e.xploited stock of Lo/igo forbesi (MoIltisca:

Cephalopoda) in the Azores. Jouma/ oj}.,larüie Bi%gica/ Association ojthe United Kigdom, 62:

799-808.

Moynihan, M &. A. Rodaniehe. 1982. Tbe beha\ior and natural bistor)' of the Caribbean reef squid

Sepioteu/his sepioidea. Am'ances in Ethology, Supplements to JoiimaI of Comp:irative Eth%gy,

•

25: 113 p.

,

OTIor:'R. K., J. A. Hoar. D. M Webber. F. G. <:arey. s. Tanalca. H. R. Martlns & F. M. Porteiro•

1994. Squid (Lo/igo !orbesi) performanCe and metabolie rates in nature. Alarine and Freshwater

Behaviour and Physi%gy. 25: 163-177.

Packard, A. &. G. Sanders. 1971. Body patterns of OctopUs vu/garis and rnaturation ofthe resPonse to

disiurbänce. Animal Behaviour, 19: 780-790.

Packard. A.1982. Morphogenesis of chfClinatophore patterns in cephalopods: are morphologica1

, physiologica1 "unitS" the same? .\fa/ac%gia. 23(1): 193-201.,

'

Packard, A. &. F. G. Hoeheberg, 1977. Skin patterning in OetopuS arid other Genera. PP. 191-231. in:

The Bi%gy oj Cepha/opods, M.N. Nixon & J.B. Messenger (Eds.). London.: Academie Press,

, Zo%gical Society ojLondon.: 1977:.615 p.

,

, "

,'

Porteiro. F. ~l &. H. R. MartinS. 1992. First finding of natUral Iaid eggs frOm Lo/igo forbesi

Steenstup. 1856 (Mollusca: Cephalopoda) in the Azores. Arquipe/ago. Life and Earth Sciences.

and

10: 119-120.

•

",.,.

poneiro",F. ,M & H. R. MartinS. 1994: 'Biology of Lo/igo jorbesi SteeDstrUp. 1856 (MoIiusca:

C.:phalopOda) in 'tbe Azores: sampie composition and rnaturation of squid caught by jigging.

Fisheries Research. 21: 103-114.

Porteiro. F. M.•. H. R. ~1artins &. R. T. Hanfon. 1990. Some obsemitionS on the beha\iour of adult

squids. Lo/igo jorbesl in eapti\;ty. Joumal oj.\larme Bi%gical Association oj rJ.K.• iO: ~594i2.

Porte:ro. F. M.• J. ~l Gon<;:l1ves. F. Cardigos. P. ~lartins & H. R. Martins. 1995. Tbe squid Loligo

jorbesi (C~phalopoda: Loliginidae) in captivity: Feeding

Gromh. Internationa/ CcJunci/ jor

Exploitation ofthe Sea.C.M. 19951K: ~1

Roper. C.• 1965. A note on .:gg deposition by DOf)teuthis plei (BlairiVille. 1823) and its comparision

with other nonh americ:m loliginid squid. Bui/elin oj.\laril1e Science. 15 (3): 589-598.

Sauer. W. H. H. &. Mo 1. SffiaIe. 1993. Spa\\ning beha\ior of Lo/igo vu/garis reynaudii in shallow

coästal waters of the south~tem Cape. South Africa. Pp ~89498. in Recent Advances in

C.!pha/opod Fisneries Bi%gy. T. Okutani. R.K. O'Dor & T. Kubodera. Eds. Tokai University

.

'

,

Press. Tok)·o. 752 pp.

Sauer. W. H. H. .. ~1. 1. Smale &. M R. Lipinski. 1992. Tbe Ioeation of spa\\ning grounds. spaWnirig

arid schooling beha\iour of of the squid Lo/igo vu/garis reynaudii (Cephalopoda: Myopsidae) off

the Eastem Cape Coast. South Africa. .\fanne Bi%g)!. 11~: 97-107.

Vecchione. M.. 1985. In-situ observations on a large squid-sp:l\\ning bed in the Eastem Gulf of

Mexico. •\la/ac%gui. 29( 1): 135-1~ 1.

.md

9