DEVELOPING AND APPLYING ECOLOGICAL THEORY TO

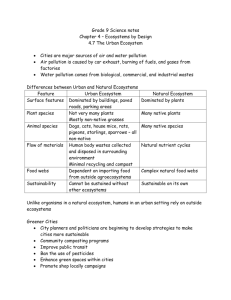

advertisement

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. DEVELOPING AND APPLYING ECOLOGICAL THEORY TO MANAGEMENT OF ECOSYSTEMS Session Summary W.H. Moir, Chair1 The human species, approaching Jl population of 6 billion on Earth, is one of Earth's most efficient predators. Effects of are analyses of ecosystem function appropriate (Salwasser, Urban, Wessman and Nel)? How do functions at one scale influence functions at another scale? Ecosystem patterns are affected by periods and intensities of disturbance regimes at whatever scales (Urban). For example, an ant can harvest green leaves from certain trees in a tropical forest, or a hurricane can level thousands of hectares of forests. A small activity, local in space and of short time intelVal, can have cumulative effects far more than the arithmetic sum of the individual activities. A complex interaction of disturbances with space-time scales can affect long-tenn ecosystem equilibria (e.g. the condition around which they tend to fluctuate in biotic and abiotic conditions). Some ecosystems may behave chaotically under certain conditions (Moir and Mowrer), and some may flip from one equilibrial state to another, such as pinyon-juniper woodlands of the American Southwest (Jameson). ' Ecosystem analysis is very much complicated by the necessity to include interactions or disciplines that are difficult to quantify or measure. Three papers in this section illustrate the importance of cultural, political, economic, and sociological nature of human activities for ecosystem analysis. Salwasser discusses how "founding principles" of ecosystem management must come from the social sciences as well as from the biological and physical sciences. The paper by Ayn Shlisky, based on work by Nancy Diaz and Dean Apostol, shows how a blend of ecosystem analysis and landscape design can result in a culturally acceptable, functional, and sustainable landscape. Their analysis transfonns narrative landscapes of desired future conditions into concrete form at a local community or watershed scale, although the analysis must necessarily also consider effects of management at other space-time scales. At a more regional scale in the Sierra Madre Occidental of northern Mexico, Aguirre-Bravo shows how cultural factors of ecosystem analysis are more limiting and problematical than biological factors. The region is currently in tumultuous disequilibrium as forest, woodland, agricultural, and pastoral ecosystems suffer intense human commodity demands. There are also cultural human activities ripple in complex ways throughout the planetaly ecosystem. Cities swollen with humans are great heterotrophic sinks, concentrating nutrients and pouring forth respiratory and industrial gases. Their autotrophic countetpart, the vast agricultural land systems, are an essential production base to support great cities. Globally, both the utban and agricultural regions are expanding ever more into remnant wildlands and forcing many other of Earth's inhabitants into marginal environments, if not outright extinction (some species are highly adaptive to human ways). Global effects of human activities influence Earth's continents, great rivers, oceans, and atmosphere. Some effects, such as radioactively contaminated sites, will last long into the future. Great issues arise about human dominance. What is the nature of the global ecosystem that will support Earth's human population at some sustainable level and at some quality of life? How is this global ecosystem composed of hierarchically organized parts? How do we keep these ecosystems sustainable, resilient to change, and productive? Papers in this session all play upon the above themes. At the global scale we must monitor the movement of nutrients and keep track of primaIy productivity (from photosynthesis) along . major climatic and nutrient gradients (Wessman and Nel). Each presentation in this session addresses the need to understand ecological processes and effects at scales of space and time ranging from macro to micro. This is a recurrent theme of ecosystem management: that the effects of populations (not just humans) upon ecosystems in which they function can vary, depending upon the scales of space and time. At what scales 1 Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Fort Collins, Colorado. 125 insensitivities that threaten ecological balances and well-being of people, plants, and animals. Dysfunctional rural ecosystems display ethnic hostilities, drug trafficking, political unrest, and execution of local leaders. Other biological consequences include loss of biological diversity and loss of the productive base of ecosystems, including soil erosion and loss of human know-how about maintenance and values of indigenous crops and medicine. . ~. The papers which follow, therefore, illustrate the breadth, difficulty, and urgency of ecosystem management viewed holistically. The reader is challenged to the near impossibility of truly understanding ecosystems in all their great complexity. In learning this lesson, we may arrive at the conclusion that the human species must first come to a deeper understanding about itself. We must be able to distinguish greed, which can lead to ecological dysfunction, from true need, which links humans into supportive and sustainable ecosystems. ..- 126