Traditional Use of Piiion- Juniper Woodland Resources -

advertisement

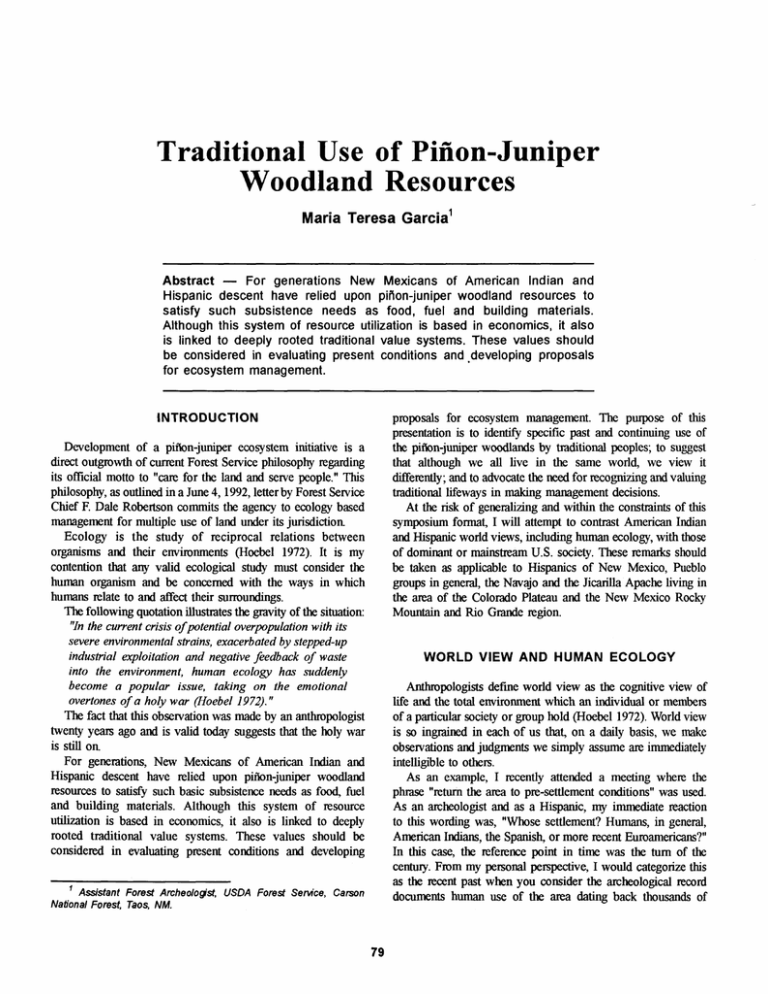

Traditional Use of Piiion-Juniper Woodland Resources Maria Teresa ~ a r c i a ' - Abstract For generations New Mexicans of American Indian and Hispanic descent have relied upon pinon-juniper woodland resources to satisfy such subsistence needs as food, fuel and building materials. Although this system of resource utilization is based in economics, it also is linked to deeply rooted traditional value systems. These values should be considered in evaluating present conditions and ,developing proposals for ecosystem management. INTRODUCTION Development of a pifbn-juniper ecosystem initiative is a direct outgrowth of current Forest Service philosophy regarding its official motto to "care for the land and serve people." This philosophy, as outlined in a June 4,1992, letter by Forest Service Chief F. Dale Robertson commits the agency to ecology based management for multiple use of land under its jurisdiction Ecology is the study of reciprocal relations between organisms and their environments (Hoebel 1972). It is my contention that any valid ecological study must consider the human organism and be concerned with the ways in which humans relate to and affect their surroundings. The following quotation illustrates the gravity of the situation: !In the current crisis of potential overpopulation with its severe environmental strains, exacerbated by stepped-up industrial exploitation and negative feedback of waste into the environment, human ecology has suddenly become a popular issue, taking on the emotional overtones of a holy war floebel 1972)." The fact that this observation was made by an anthropologist twenty y e m ago and is vahd today suggests that the holy war is still o n For genemtions, New Mexicans of American Indian and Hispanic descent have relied upon piiion-juniper woodland resources to satisQ such basic subsistence needs as food, he1 and building materials. Although this system of resource utilization is based in economics, it also is linked to deeply rooted traditional value systems. These values should be considered in evaluating present conditions and developing ' Assistant Forest Archeologist, USDA Forest S e ~ c e ,Carson National Forest, Taos, NM. proposals for ecosystem management. The purpose of this presentation is to i d e m specific past and continuing use of the piibn-juniper woodlands by tmditional peoples; to suggest that although we all live in the same world, we view it Weerently; and to actvocate the need for recognizing and valuing traditional lifeways in making management decisions. At the risk of generalizing and within the constraints of this symposium format, I will attempt to contrast American Indian and Hispanic world views, including human ecology, with those of dominant or mainstream U.S. society. These remarks should be taken as applicable to Hispanics of New Mexico, Pueblo groups in general, the Navajo and the Jicarilla Apache living in the area of the Colorado Plateau and the New Mexico Rocky Mountain and Rio Grande region. WORLD VIEW AND HUMAN ECOLOGY Anthropologists define world view as the cognitive view of life and the total errvironment which an individual or members of a particular society or group hold (Hoebel 1972). World view is so ingrained in each of us that, on a dady basis, we make observations and judgments we simply assume are immediately intelligible to othes. As an example, I recently attended a meeting where the phrase "return the area to pre-settlement conditions" was used. As an archeologist and as a Hispanic, my immediate reaction to this wording was, "Whose settlement? Humans, in general, American Indians, the Spanish, or more recent Euroamericans?" In this case, the reference point in time was the turn of the centwy. From my personal pespective, I would categorize this as the recent past when you consider the archeological record documents human use of the area dating back thousands of years. While the speaker and I may have had the same physical landscape in mind, our world views created vastly different perceptions of it. Cultures, like ecosystems, are dynamic entities. Contemporary American Indians and Hispanics are neither frozen in time nor relics of an idealized past. They are modern peoples who, in spite of formidable odds, reflect the principle of cultural continuity. That is, they retain certain common traits by whlch they can be identified as distinct cultural groups when considered within the context of modem U.S. culture. These common traits include observable behavioral patterns and norms related to such aspects of life as language, religion, kinship, social organization, and subsistence patterns. Characterization of these traits as "traditional" indicates they derive from each group's historic past. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish in New Mexico, American Indians had developed complex economic systems in response to their physical and cultural needs. The archeological and ethnographic records document substantial information about their settlements, technology and material culture, tool manufacture and use, religion, techniques of food extraction and production, diet, and social organization Given population estimates and distributions at the time of contact, it is safe to characteriz their ecological adaptation as successful rather than marginal. The piiion-juniper woodland is an example of what can be called a micro-environment within the Southwestern environmental setting. For prehistoric and historic peoples, it was viewed as a storehouse of resources dominated by piiion and juniper species but also included various species of shrubs, herbs, grasses, roots, tubers, berries arbd large and small game. These resources were used to meet personal and group needs ranging from food, he1 and building materials to tools, clothing, and medicine. American Indian world view fostered then, as it does now, a holistic sense of place and reliance upon one's surroundings. More important, it ascribed little difference between people and the natural world (Bane 1990). This perception is embodied in Robert Lake's (1990) writing on the Law of Reciprocity: "By following the Law of Reciprocity, we will receive the energy, spirit, and power of the thing we harvest and use; not just its physical part. Life is a reciprocal relationship. We have a mutual dependence upon each other for survival, and we should always remember that in our dealings with our relations in Nature, the Spirits, the Great Creator, and each other...that it is an exchange of privileges." In addition to this precept, American Indian views on landholding also are relevant to this discussion. Throughout the Southwest, concepts of land tenure varied to some extent from group to group, but in general, all Pueblos, the Navajo and the Jicarilla Apache recognized various forms of what we would term private ownership of agricultural lands (Jorgensen 1983). Ownership might be vested in individuals, clans or extended families, but there was a mechanism for establishing and delimiting personal space. Access to hunting and gathering areas, such as the pifion-juniper woodland, on the other hand, was communal or influenced by what has been called a communitarian ethic (Jorgensen 1983). This ethic prescribed that individuals organized into a unit, such as a pueblo or tnbe, shared or used available resources w i t h certain territorial limits. The ramifications of the Spaniards' arrival in the New World were debated at length during 1992 and are not an issue here. Rather, the focus is on the cultural legacy that has survived since contact with native peoples and the reality that combination of American Indian and Spanish traits has contributed the primary components to what we i d e n e as contemporary Southwestern culture. Further, it is significant that despite the fact the Spanish came from what has been described as a world of "...patron-client social relations, material wealth, iron tools, food markets, domesticated animals, Aristotelian logic and divine right (Ford 1987)," they shared with American Indians a deep respect for land and water and held similar notions regarding land tenure. Alongside the original inhabitants of this region, the Spanish devised a subsistence pattern or ecological adaptation suitable to their newly adopted home. What developed as the tmditional Hispanic land ownership system in New Mexico has been characterized as: "...in many respects the reverse of the Anglo-American system. It included both individual and community land grants, the latter being the most common form in northern New Mexico. ... The community land tenure system was not a fee simple system; rather it centered on private agricultural landholding, encumbered by various collective constraints, and communal pasturage and woodlands with individual rights of usuj?uct (Van Ness and Van Ness l98O)." Usufruct is a legal term and can be defined as the individual's right to utilize and enjoy the benefits and advantages of something belonging to another or all, such as the woodlands, as long as the use is judicious. This practice is in direct contrast to the medieval English system whereby the King owned and controlled all resources in the forest. Access to these resources was restricted by the sovreign, and landless peasants were not allowed to cut trees or harvest game. Violation of these restrictions was dealt with by severe penalties. Thus, because their world view was more similar to that of American Indians, Spanish settlers of New Mexico developed a similar economy based on what they could produce on private agricultural lands coupled with what they could obtain from the surrounding environment. By the turn of the century or "pre-settlement times," both American Indians and Hispanics had become part of a larger, more diverse population in New Mexico. In response and as part of the natural selection process, both groups attempted to adjust to changed conditions and circumstances. Among the most dramatic changes were a permitting process for obtaining resources and grazing, and large scale, commercial harvesting of forest commodities from what they both considered ancestral lands. Wage labor in the mining, timber and grazing industries also became a option People who for generations had been essentially self-sufficient, and had used barter as a means of obtaining products and services were drawn into a market economy. Social and technological change continued to be introduced into their environment, yet many American Indians and Hispanics choose to live in culturally prescribed ways: retaining what land is still theirs; fanning family plots; gathering wood for heating and cooking; grazing family herds;hunting and gathering in the woodlands each year to supplement their diet, prepare traditional foods and obtain materials for producing secular and ritual objects. This is a subsistence pattern that persists today. It is a circular, experiential pattern of living rather than one learned by taking part in Earth Day activities or earning a degree in Environmental Education It is a deeply rooted pattern held in high esteem by its practitioners. Finally, it is a pattern that effectively integmtes traditional peoples' articulation between their social and natural environments. CONCLUSIONS In conclusion, the relationship between traditional peoples cultures and their environment must be considered as we pursue strategies for sustainable stewardship of the pifion-juniper woodlands. The wants and needs of these people must be examined in terms of personal and special uses, economic opportunities, recreational activities, and spiritual values. These wants and needs, in turn, must be balanced with concern for the physical and biological dimensions of the ecosystem. Failure to do so would be nothing less than environmental ethnocentrism whereby traditional ecology is judged according to the practices and standards of non-traditional people or the hard sciences. It is presumptuous to assume that meeting these wants and needs correlates with irresponsible behavior or conspicuous consumption of resources. For example, the cutting and burning of green piiion was not an historic practice. It is a more recent phenomenon that has increased with use of the chainsaw and in proportion to population growth in the Santa Fe and Albuquerque areas. It is a small scale, quick cash pursuit in reaction to modem preference. And, for th~sreason, it is a practice easily modified partxularly if replaced by an alternate economic opportunity. People are part of the ecosystem. Exploring and understanding the human dimension in ecosystem management is a challenge we must accept if we are to be sincere in our intent to formulate and make sound management decisions. LITERATURE CITED Bane, G. Ray 1990 Through Native Eyes. pp. 3-6. In: J. Holmaas (ed.) Interpretation: Fall 1990 Interpreting Native American Cultures. National Park Service, Washington Office, Division of Interpretation, Washington, DC. 38 pp. Ford, Richard I. 1987. The New Pueblo Economy. pp. 73-91. In: When Cultures Meet: Remembering San Gabriel del Yunge Oweenge. Papers from the October 20, 1984 Conference Held at San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico. Sunstone Press, Santa Fe, NM. 96 pp. Hoebel, E. Adamson 1972. Anthropology: The Study of Man McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, NY. 756 pp. Jorgensen, Joseph G. 1983. Comparative Traditional Economies of Ecological Adaptations. pp. 684-710. In: A. Ortiz (ed.) Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 10 Southwest. Srnithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. 868 pp. Lake, Robert 1990 Law of Reciprocity. pp. 18-19. In: J. Holrnaas (ed.) Interpretation: Fall 1990 Interpreting Native American Cultures. National Park Sewice, Washington Office, Division of Interpretation, Washington, DC. 38 pp. Van Ness, John R.; Van Ness, Christine M. 1980. Introduction pp. 1-11. In: J. R. and C. M. Van Ness (eds.) Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in New Mexico and Colorado. Sunflower University Press, Manhattan, KS. 119 pp.