Ecology and Diversity of Piiion-Juniper Woodland Mexico

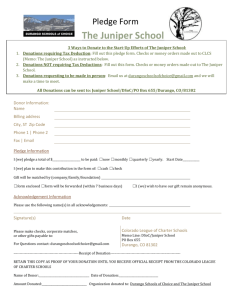

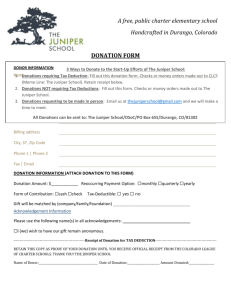

advertisement

Ecology and Diversity of Piiion-Juniper Woodland in New Mexico William A. ~ i c k - ~ e d d i e ' Until recently there has been little research conducted upon woodland vegetation This has been largely because woodland vegetation was of less economic importance than either forest or grassland vegetation. OCCURRENCE OF PINON-JUNIPER VEGETATION One of the most important factors dictating where a given type of vegetation is found is "available moisture". Available moisture is a complicated factor. It is a function of precipitation (amount, form, season, frequency, and intensity); infiltration rate (surface material and slope); percolation (soil structure and texture); and rate of evapo-transpimtion from plants and soil. Vegetation types have different avdable moisture requirements. It is not surprising then that in New Mexico, forest, woodland, grassland, and scrubland are established on a gradient of decreasing available moisture. Woodland has a higher available moisture requirement than grassland but lower than that required by forest. CHARACTERISTICS AND DIVERSITY OF PINON-JUNIPER WOODLAND AND JUNIPER SAVANNA Woodlands are characterized by tree species whose canopies do not overlap and whose sizes are smaller than top-canopy forest tree species. Tree density in woodlands varies from 280 treeslacre down to 130 treeslacre. Scattered stands with densities of less than 130 treeslacre are considered to be savanna starads. This symposium is concerned with one type of woodland Piiion-Juniper Woodland. Even though there are no piiion pines in New Mexico savannas, the juniper savannas are considered part of the Piiion-Juniper Ecosystem at this symposium. You must remember that Piiion-Juniper Woodland in New Mexico includes a number of different species in different combinations, in Merent parts of the state. The composition and structure of ' Professor Emeritus, Department of Biology, New Mexico State Univeru'ty, Las Cruces, New Mexico. the Piiion-Juniper types vary on an available moisture gradient. Moir and Carleton (1987) proposed three subzones of woodlands for New Mexico as follows: 1. Mesic (cool, wet) closed woodlands - Tree cover: 50-80%, Height of tallest trees: 7-13m 2. Typical or model open woodlands - Tree cover: 30-50%, Height of tallest trees: 4-8m 3. The aridic (warm, dry) juniper savannas Tree cover: 5-30%, Height of tallest trees: 5m There are two species of piiion pine found in New Mexico. They are the Colorado Piiion (Pinus edulis), and Border Piiion (I! discolor). There are six or seven species of juniper in the state but the most widespread are Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana), One-seed Juniper (J. monosperma), Rocky Mountain Juniper (J. scopulorum), and Utah Juniper (J. osteospema). I have classified the vegetation of Piiion-Juniper Woodland and Juniper Savanna found in New Mexico (Dick-Peddie, 1993). Series as used by the Forest Service was used as the category above the basic category of Association (Community type or Habitat type). The classification recognized the following Series (the number in parentheses is the number of distinct Associationfound in the Series): Coniferous Woodland Colorado PifionUne-seed Juniper Series (10) Colorado Piiion-Alligator Juniper Series (4) Colorado Piiion-Utah Juniper Series (1) Colorado Piiion-Rocky Mountain Juniper Series (1) Colorado Piiion-Mixed Juniper Series (3) Colorado Piiion-Mixed Juniper Series (1) Mixed Woodland Colorado Piiion-Oak-Juniper Series (2) Savanna One-seed Juniper Series (8) One-seed Juniper-Rocky Mountain Juniper Series (1) Utah Juniper Series (1) You can see that the greatest number of Associations (10) are found in the Colorado Piiion-One-seed Juniper Series. This series is the most widespread in the state. It is interesting that Woodin and Lindsey (1954) noted that although One-seed Juniper was the most important juniper in New Mexico woodlands, it is replaced in the north (Colorado) by Rocky Mountain Juniper and in the south (Mexico) by Alligator Juniper. Alligator Juniper is usually found in New Mexico at the upper limits of the P-J Woodland and some even suggest that Alligator Juniper is a subdominant member of the Ponderosa Pine Forest in much of the state. Large old Alligator Junipers are found in the Sacramento Mountains in areas which were cleared of Ponderosa forest in the past. I have outlined for you the type and degree of diversity found in the Piiion-Juniper Woodland and Juniper Savanna vegetation of New Mexico. It is obvious to all of us that Piiion-Juniper Woodland and Juniper Savanna are generalized, generic terms and that single or uniform management schemes cannot be successfully applied to these diverse ecosystems. Each Series or possibly even each Association should be approached independently as to manipulation and management. the establishment (ecesis) of a species on a new site denotes that there is not only an opening in the community but that the microhabitat meets the needs of the new arrival. Knowledge of this ecology avoids the misleading concept implied by the terms "invasion" and "invader". These terms imply a dynamics of the advance of one species into another species' habitat and outcompeting it, thereby pushing it out. A great deal of money has been spent over the years, based upon this "invader" premise, to remove the "invader" species as the culprit responsible for the decline in vigor and density of the initial species. Rather it should be assumed that the establishment of the "invader" species serves as an indicator or symptom that the initial habitat has been modified and may no longer be optimum for the initial species. My view is that the rapid increase in the amount of juniper savanna in New Mexico over the past 100 years is an example of ecesis following microhabitat modification A more striking example can be seen in northcentral to northwestern New Mexico where the microhabitat has been so modified that grassland vegetation has disappeared and there now is a transition from Piiion-Juniper Woodland to Great Basin Desert Scrubland. Changing patterns where Colorado Piiion is expanding appears to actually be its re-establishment on previously Piiion-Juniper sites (Sallach, 1986). I would suggest that brush removal on grasslard might well hasten gr;lss recovery provided that post-removal management rectifies the situation which allowed the brush to become established in the fmt place. If such management is not economically feasible, periodic removal will be necessary. CHANGED AND CHANGING PATTERNS OF PINON-JUNIPER AND JUNIPER SAVANNA VEGETATION LITERATURE CITED Lastly, I want to address changes in the patterns of Piiion-Juniper and Juniper Savanna vegetation during the last 100 years. Synecologists (community ecologists) have been wrestling with the concept of "competition" for many years. It now appears that in plants competition is at best subtle and may only be operative at the time of germination. Actually, as we instruct our young school children, plants tend to "share" the environment. In fact we should expect selective pressures to stimulate a reduction of competition through the incorporation of adaptations which permit a species to use different features of the environment and/or at Merent times than other species in the habitat. I have gone in to this so we will understand that Dick-Peddie, W.A. 1993. New Mexico vegetation: past, presea and future. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, NM 244. Moir, W. H.; Carleton, J.O. 1978. Classification of pinyon-juniper (P-J) sites on National Forest in the Southwest. In: Proceedmgs Pinyon-Juniper Conference. USDA Forest Service General Tech Rpt. INT-2 15S 81 Sallach, B.K. 1986. Vegetation changes in New Mexico documented by repeat photography. Thesis. New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM. 68. Woodm, H.E.; Lindsey, A.A. 1954. Juniper-pinyon east of the Continental Divide as analyzed by line-strip method. Ecology. 35: 473-489.