Pifion-Juniper Initiative in the Southwestern Region W. shawl Douglas

advertisement

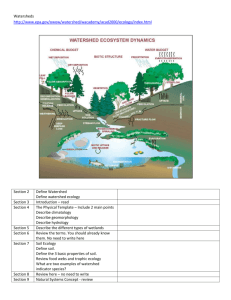

Pifion-Juniper Initiative in the Southwestern Region Douglas W. shawl INTRODUCTION I want to share a little background on the Southwestern Region's piilon-juniper initiative. A little over a year ago, when our Regional Forester was relatively new in this Region, he was approached by several p u p s and individuals about the need for enhanced management in our piilon-juniper woodlands (P-J). The emphasis placed by these people was the watershed codtion in the P-J. The need to improve watershed conditions was also noted in our 1991 Stewardship Review Report and was an expressed concern of many of the Region's line officers. As a result of these concern, our Regional Forester selected P-J woodland management as one of his two resource initiatives. The other resource initiative is forest health, which focuses more on fuel loading and insect and disease conditions at the uhan interface; stand densities in the pine, mixed conifer, and woodland types; and riparian conditions. So there are some mutual concerns shared by these two initiatives, and they will be coordinated in an ecosystem management context. PROBLEM ASSESSMENT Because of the watershed nature of this initiative, the lead coordination role was assigned to the Region's Director for Watershed and Air Management. To better address the variety of P-J issues and concerns around the Region, an assessment team was chartered for each state. Each team was led by a Forest Supervisor and included at least one District Ranger and the resource people required to accomplish the assessment. The teams were also charged to define a desired condition, estimate costs and potential accomplishments for a five-year program, and iden@ potential partners. All thls was to be accomplished in a rather short time. The Region's Terrestrial Ecosystem Survey (TES) was used to derive an estimate of the P-J acres in the Region The TES is an ecological k e n t o q in which soils, vegetation, climate, and landform are inventoried and intepted into an ecological map unit. We looked at all the woodland vegetation associations that have piilon andlor juniper as a si@icant part of the ' USDA Forest SeM'ce, Southwestern Region, Albuquerque, NM. overstory. Based on the TES review, we have about seven million acres of P-J in the Region This is slightly less than a third of the Region Another screen of the TES data was used to estimate the P-J acres in impamd watershed condition The criteria used for this screen included sheet, rill, and gully erosion, and soil compaction Based on this screen we estimated there are about 3.5 million acres in impaired or unsatisfactory watershed condition; of these, about 1.9 million acres are in Arizona and 1.5 million in New Mexico. People b e many theories for why these acres are in unsatisfactory watershed condition; over-grazing in the early part of the century, control of fire, and climate changes are frequently cited. Realizing that these and other causes and their cumulative effects are all part of the history of the P-J, we didn't focus a lot of time on ide-ing the cause; rather, we focused more on what we can do to make changes for improvement. We also realized the potential for change varies between ecosystems or habitat types. Some systems can now be managed for small wood products, some for more grasses, shrubs a d fohs, but some have been changed to the extent their former potential for productivity is no longer available. Some soils are changed due to erosion and drying. WHAT DO THE PROBLEM AREAS LOOK LIKE? Pictures of typical problem areas include P-J stands with b m and e r e interspaces between the tree canopies. Watershed conditions under the canopies are good, but the vegetation cover and diversity between the trees is less than desirable to meet forest land management plan objectives. As a consequence, sheet and rill erosion are common Enough soil has moved on some sites that an erosion pavement is exposed, reducing further sheet erosion but accelemtmg gully erosion. Down-slope sites frequently include gully emsion that is drying previously grassy bottoms and riparian areas. These grassy bottoms were effective in slowing runoff from the steeper side slopes, but now they have veq effective drainage systems that move water rapidly off site with eroded soil. People have lived in the P-J for thousand of years. They derived much that they needed from the wildlife and vegetation available. Piiion nuts, for example, furnished an important part of their protein and d i e w fat. Some early cultures derived spiritual values from the P-J, and their successors still do. As a result of this long history of habitation, there is a high density of cultural resource sites in the P-J. These resources are sometimes damaged by erosion. We still like to live in the P-J: the climate is good, the landscape is aesthetically pleasing, and the land is suitable for construction and other uses. However, today there are a wide range of values and opinions about the P-J. Some consider the P-J public enemy number one, others have a spiritual tie, while others look to the P-J for social needs like nut pickmg and fuelwood gathering as family activities that provide home needs and income. AU these values must be addressed in our initiative. THE PROGRAM A study of research on past and c m n t P-J management practices was completed by the Watershed and Air Staff. We reviewed all the research publications we could find fiom the past several decades, pulled out important findings and watershed recommendations, and published them in a document titled "Watershed Management Practices for Piiion-Juniper Ecosystems." This document is intended as a reference for Districts planning projects. Based on our experience with P-J pmctices and project coordination requirements, the state teams estimated we could implement improved ecosystem management on approximately 70,000 acres per year in the Region The average cost for this improved management is estimated to be $100 per acre, Thus, to implement and sustain our P-J initiative, we will need a budget of $6.5 to $7 million per year. What are we trying to achieve with our P-J initiative? The desired future condition for each project must be determined by integrating the biological, physical, cultural, social, and economic needs of each ecosystem. However, at a Regional or programmatic level, we want each desired future condition to include the following criteria: (1) improvement of long-term soil productivity; (2) water quality that meets state standards; (3) a wide range of plant and animal diversity; (4) sustainable ecosystems; (5) recognition of the P-J as a valuable ecosystem for uses, products and values; (6) a visually desirable mosaic of vegetation conditions on the landscape; (7) riparian areas managed for their potential and uniqueness; (8) threatened, endangered and sensitive plant and animal habitats protected; (9) historic and pre-historic cultural values protected; and (10) management that is sensitive to lifestyles as well as ecosystem needs. WAYS TO REACH A DESIRED FUTURE CONDITION There are many tools available to help move us toward a desired future condition. Some of these tools are discussed in "Watershed Management Practices for Pifion-Juniper Ecosystem." Each project team must decide which tools are most appropriate and how they should be applied to meet specific objective. All the values held by people for each site must be considered in selecting the appropriate tools and techniques. An example of one technique is fuelwood harvesting followed by lopping and scattering the slash over bare soil areas. This technique provides several benefits. People are employed, a product is hawested, and a microclimate is established near the soil that enhances conditions for the establishment of grasses and shrubs. Fire may also be an important tool for initiating change and maintaining desired conditions. However, we need to better understand the trade offs in the form of soil nutrient losses when we use fire. Projects must integrate management techniques and tools from many resources, including wildlife, range, recreation, cultural resources, timber and engineering. Plans must focus on achieving desired future conditions with products as additional results of that achievement. The way we move toward desired future conditions may be as important to some people as achieving the end result. Thus, some tools may not be acceptable. PARTNERSHIPS Potential partners are available in other state and federal natural resource agencies and among interest groups like the Soil and Water Conservation Districts. Grazing germittees and adjacent land owners are also w d h g partners. WHAT ARE SOME BENEFITS? Benefits of our P-J initiative include a visually desirable mosaic of vegetation conditions including diversity of both overstory and understory components; soil, water, and air quality that meets legislative and administrative goals; a wide range of plant and animal diversity; and management that is sensitive to the public's life style needs as well as ecosystem needs. Economic benefits include Ilevenue to local economies from fuelwood, pifIon nut, Christmas tree and wildmg sales, and increased forage for livestock. Resource benefits include improved wildlife habitat, improved riparian areas, protected archeological sites, and reduced road densities.