of rm Trends in Abundance Amphibians,

advertisement

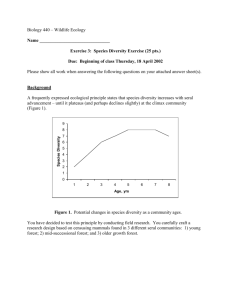

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Abstract.-Relative abundance of 55 species of amphibians, reptiles, and mammals was estimated at 166 sites representing early clearcut through oldgrowth Douglas-fir forest in northwestern California. Nine species were strongly associated with older stands and 1 1 species were strongly associated with younger stands. The remaining species were either too rare to analyze statistically (22 species) or exhibited no clear trends of abundance in relation to stand age (1 3 species). Estimates of relative abundance of each species in each stage, coupled with data on historical, present, and future acreage of timber in each seral stage, were used to approximate the long-term impacts of timber harvest on the fauna of the Douglas-fir region in northwestern California. rm Trends in Abundance of Amphibians, eptiles, and Mammals in Douglas- Fir Forests of tern California1 Martin 6.Raphael2 Management of old-growth Douglasfir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) forests is controversial in the Pacific Northwest, primarily because of the possible value of old-growth as habitat for certain wildlife species versus the revenues represented by old-growth trees (Meslow et al. 1981, Harris et al. 1982).Management to provide wildlife habitat requires an inventory of associated wildlife species and an assessment of their old-growth dependency. An analysis of the size and distribution of habitat patches necessary to support viable populations of those species is also critical (Burgess and Sharp 1981, Rosenberg and Raphael 1986, Scott et al. 1987). This study describes the relative abundance of amphibians, reptiles, and mammals in six seral stages representing clearcuts, young timber stands, and mature forest in northwestern California. These estimates of relative abundance were used to project probable long-term changes in population size of amphibians, reptiles, and mammals as each seral 'Paper presented at Symposium, Management of Amphibians, Reptiles and Small Mammals in North America (Flagstaff,AZ, July 19-27. 1988). Research Ecologist, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, 222 South 22nd Street, Laramie, Wyoming 82070. stage responds to forest management practices. METHODS Stand Selection Study stands were on the Six Rivers, Klama th, and Shasta-Trinity National Forests within a 50-km radius of Willow Creek, Calif. Forest cover was dominated by Douglas-fir, usually in association with an understory of tanoak (Lithocarpus ensiflorus) and Pacific madrone (Arbutus menziesii). Elevations varied from 400 to 1300 m. Stage Seral state 1 Early 2 3 Late Pole 4 5 Sawtimber Mature 6 Old-growth Age (yrs) 10-20 "O 20-50 50150 150-250 >250 Raphael and Barrett (1984) describe methods for aging these stands. Ground surveys were used to verify stand conditions. Forest Service stand designations were used to guide stand selection, but the final classification of each stand into seral stages was based on measured vegeta tion characteristics. The study region is characterized by warm, dry summers and cool, wet winters; total precipitation averages 60-170 cm per year. After selecting potential study stands using timber maps and aerial photographs, I then located all stands that were accessible by road, were relatively homogeneous with respect to tree cover, included no large clearings or other anomalous features, and were free from scheduled timber harvest for at least the next 3 years. From this restricted subset of stands, I randomly chose 10 to 15 stands representing each of six seral stages: > > > Classification Clearcut (brush/sapling) Young forest (pole/sawtimber) Mature forest Vegetation Sampling The structure and composition of vegetation on each stand in the three older seral stages was measured in three, randomly selected, 0.04-ha circular subplots within a 90-m radius of each plot center. Within each subplot, observers recorded species, height, diameter at breast height (d.b.h.) and crown dimensions of each tree or shrub >2.0 m tall. In addition, all trees >S)O-cmd.b.h. were counted on one 0.50-ha circular subplot centered on the plot. This sample permitted a better estimate of the density of large-diameter trees. Numbers of larger ( S c m diameter) logs and volume of other downed woody debris were estimated along a 30-rn transect crossing the center of each 0.04-ha subplot (Brown 1974). Marcot (1984) sampled vegetation in a similar manner on stands in the three early-sera1 stages. Vertebrate Sampling All field data were collected by a team of three to six biologists. We used a variety of techniques to sample various taxonomic groups. Pitfall Arrays We used pitfall arrays to capture small mammals (especially insectivores), reptiles, and salamanders. An array was composed of ten 2-gallon plastic buckets buried flush with the ground and covered with plywood lids, arranged in a 2 x 5 grid with 20m spacing. We placed one array within each stand center and checked traps at weekly to monthly intervals from December 1981 (sawtimber, mature, old-growth; n = 27,56, and 52 sites in each stage, respectively) or August 1982 (early shrub-sapling, late shrub-sapling, pole; n = 10 sites each) until October 1983. All live animals were marked and released; recaptures were excluded from analyses. Dead animals were collected and prepared for permanent deposit in museum collections. Results for each species were expressed as captures per 1000 trapnights on each stand. Raphael and Rosenberg (1983)demonstrated that abundance estimates (capture rates) had stabilized after 15 months of continuous trapping. Drift Fence Arrays To better sample snakes, we installed a drift fence array (Campbell and Christman 1982, Vogt and Mine 1982) on each of 60 randomly selected stands (10 of each of the three early stages and sawtimber, 8 mature, and 12 old-growth). An array consisted of two 5-gallon buckets placed 7.6 m apart and connected by an aluminum fence 7.6 m long and 50 cm tall with two 20 x 76 crn cylindrical funnel traps, one on each side of the center of the fence. These fences were operated from May through September 1983. All captures were combined with those from the pitfall arrays along with the associated trapnights from each stand. Track Stations Tracks of squirrels and other larger mammals were recorded on each site on a smoked aluminum plate baited with tuna pet food (Barrett 1983, Raphael and Barrett 1981, Raphael et al. 1986, Taylor and Raphael 1988). Based on results of a pilot study (Raphael and Barrett 1981), observers monitored each station for 8 days in August or September in 1981-1983, sampling 20 stations in each of the three early stages and 81,168, and 157 stations in the sawtimber, mature, and old-growth stages, respectively. The proportion of stations in each seral stage on which a species occurred was as an index of that species' abundance. Livetrap Grids To better estimate abundance of small mammals that were liable to escape from pitfalls, we established 27 livetrap grids (3 in each of the three earliest stages and 5,7, and 6 in the three later stages), each of which usually consisted of 100 25-cm Sherman livetraps arranged in a 10 x 10 grid with 20-m spacing. Other grid sizes or shapes were used when the plot configuration would not contain the standard grid. Traps were checked each day for 5 days (based on pilot studies, Raphael and Barrett 1981) during July in 1981 (late stages only), 1982, and 1983 (all stages). Results for each species were expressed as mean number of captures per 100 trapnights. Surface Search To better sample certain amphibian species, we conducted time- and area-constrained searches (Bury and Raphael 1983, Raphael 1984) on a subset of sites in 1981 (late stages), 1982, and 1983 (all stages). A twoperson team searched under all movable objects and within logs on three randomly located 0.04-ha circular subplots (fall 1981,1982)or within a 1-ha area for 4 working hours (spring 1983). We conducted 20 surveys in each of the three early stages and 29, 39, and 48 surveys in the three late stages. Opportunistic Observations Observers recorded the presence of vertebrates or identifiable vertebrate sign incidental to the above procedures. We tallied observations to calculate frequency of occurrence of rarer species within each stage. Forest Area Trends Estimates of historical, current, and future acreage in each seral stage were taken from Raphael et al. (in press). For these analyses, I combined similar pairs of seral stages into three generalized stages representing brush/sapling, pole/sawtimber, and mature timber. I then computed relative abundance of each vertebrate species in these three stages using a weighted average (weights based on sampling effort)of estimates from each of the two stages forming the pair. Population estimates for historical, present, and future time periods were computed using the formula: where Pit was the relative population size of the ith vertebrate species at time t, Dij was the relative abundance of the ith vertebrate in the jth seral stage, and A, was the total area of each of the three seral stages at time t. canopy volume, basal area, litter depth, and density of Douglas-fir stems >9O cm d.b.h. Downed wood mass differed among stages, but the greatest volume occurred in the youngest stands, probably in the form of logging slash, and the lowest volume occurred in pole and sawtimber stages. Early-sera1 stands were higher in elevation than older stands, probably because of the logistics of timber harvest in the area (most clearcuts were located along ridgetops). Stands in the two earliest seral stages, also because of logging, were smaller in area than stands in the four older stages. RESULTS Vegetation Structure Comparisons of vegetation structure among the seral stages (table 1) showed that older stands had greater Vertebrate Abundance and Diversity Among all plots and years of study, we recorded 9,928 captures of all species during 898,431 trapnights from pitfalls and drift fences; 1,636 captures of amphibians during surface searches; 3,066 small mammal captures during 35,070 trapnights from livetrap grids; and 510 detections of larger mammals from track stations. Relative abundances of 55 species, based on the most appropriate sampling method for each species, are summarized in table 2. Values are comparable across stages but not among taxa if different sampling methods were used. Amphibians were much more abundant in forested than in clearcut stands, whereas reptiles were more abundant in clearcuts. None of the amphibians and reptiles [except rarer species such as northwestern salamander (see appendix for scientific names of vertebrates)] was absent from any stage. Mammals exhibited a greater variety of responses to seral stage. Some (e.g., Douglas' squirrel, western redbacked vole) increased in abundance from earliest to latest seral stages; others (e.g., deer mouse) decreased along this gradient. A number of species (eg., Allen's chipmunk, duskyfooted woodrat, pinyon mouse, California vole) were most abundant both in late shrub-sapling and mature or old-growth stands. Mean numbers of mammal and reptile species recorded per stand differed among seral stages, but mean numbers of amphibian species did not differ significantly (fig. 1). Among mammals, mean numbers of species were greatest in mature and old-growth stages. In contrast, mean numbers of rep tile species were greatest in the two earliest stages. Long-TermTrends Estimates of land area in each seral stage through time (table 3) indicate more area is occupied by early seral stages currently than during historic or future times. Mature and oldgrowth stages currently occupy about half of historic acreage, and these stages will probably occupy only about 30% of current acreage under the most likely harvest patterns of the future (table 3). The implications of these changing distributions of seral stages for amphibians, reptiles, and mammals are summarized in figure 2. Nearly equal numbers of species are likely to have increased or decreased by more than 25% relative to historic abundance at present and in the future. Three of the five reptile species are presently more abundant than in historic times and all five species will likely be more abundant in the future. Amphibians showed an opposite pattern. Four of the eight species are presently less abundant and five of the eight may be less abundant in the future. Among the 20 mammal species, seven are presently less abundant than in historic times whereas five are more abundant. Eight species will probably be less abundant in the future and six more abundant. DISCUSSION Abundance in Seral Stages Results suggest late brush/sapling and mature/old-growth seral stages provided more productive wildlife habitat than early brush/sapling, pole, and sawtimber stages. Among amphibians, only ensatinas were captured frequently in pole sites. Clouded salamanders were generally under bark or inside downed logs and persisted in clearcut stands as long as adequate numbers of logs were retained, especially in late sites (Raphael 1987, Welsh, this volume). Lizards were more abundant in earlier seral stages than in pole and mature stages. Among snakes, only sharp-tailed snakes were observed on early sites; other species occurred on later sites. However, sampling was not sufficient for definitive conclusions. With the exception of the deer mouse, small mammals were more abundant on late bmsh/sapling sites. Dusky-footed woodrats were of special interest in this regard as we observed many woodrat nests built among the stems of tanoak and Pacific madrone in late brush/sapling sites. The combination of abundant mast, good nesting substrate, and protection from predation (spotted owls rarely forage in old, brushdominated clearcuts) provided by the dense, brushy cover were probably the reasons that woodrats and other small mammals were more numerous in late clearcut sites (Raphael 1987). Tree squirrels were most abundant in mature forest sites and ground squirrels were more abundant in early clearcut sites. Chipmunks were the only squirrel that reached peak abundance in early sera1 sites. Their abundance was correlated with the cover of tanoak in the understory (Raphael 1987). Management actions, such as herbicide treatments, that shorten or delete the late brush/sapling stage are probably detrimental to chipmunks, woodrats, and certain other rodents. Several carnivorous mammals were abundant in the late brush/sapling stage. Greater prey density in late compared to early and pole sites may explain this higher frequency of carnivores although more data will be necessary to confirm this observation. Of the 55 species observed, 20 were strongly associated with either older (9 species) or younger (11 species) stands (table 4). Three salamanders and six mammals were associated with older stands. One toad, one frog, five lizards, and four mammals were associated with younger stands. Five species associated with old-growth were also abundant in late (brushy) clearcut stages (table 2). These species peak in abundance in old stands and late clearcuts, with low abundance in intermediate age classes. L I 1 1 I I 4 5 1 SEW STAGE n n -3 -2s D a so n >n CHANCl N MMwuf ( X ) Figure 1 .-Mean numbers of amphibian, reptile, and mammal species observed in serel stages of Douglas-firforest, northwestern California, 1981-1 983. Sera1 stages (and numbers of stands sampled) are: 1 - early brush/sapling (n = 10); 2 late brushlsapling (n = 10); 3 - pole (n = 10); 4 sawtimber (n = 27); 5 mature (n = 56); 6 old-growth (n = 53). Vertical lines indicate 9Sohconfidence intervals. - - - - Figure 2.-Percent change in population size of amphibian, reptile, and mammal species at present and in the future relative to estimated historical populations. Histograms represent the numbers of species increasing or decreasing by specified percentages. I examined habitat associations among each of the above 9 species by computing correlations of their abundance with specific habitat components (table 5). Density of large trees and hardwood volume were correlated with the abundance of most species. Moisture, as measured by the presence of surface water, moisture-loving tree species, or north-facing slopes, was important for most mammals and one salamander species. Four mammal species were signi ficantl y more abundant on higher elevation stands. Downed wood volume also was significantly and positively correlated with abundance of four amphibian and mammal species. The abundance of hardwoods in the understory was important for many species in each group. In contrast, snag density was not positively correlated with the abundance of any species. Long-Term Trends The list of sensitive species (table 4) is tentative pending results of addi- tional surveys and more intensive, species-specific research. The projections, although based on an intensive sampling effort, are highly speculative. Three assumptions must be recognized to interpret these results. First, I assumed that greater relative abundance in a seral stage indicates a species' preference for that stage and that preferences remain constant with shifting distri5ution of acreage in each stage. Some species have (or could) adapt to new stages over time. Second, I assumed total acreage of each seral stage can be used to estimate responses of vertebrates without regard to size and juxtaposition of stands comprising each stage. However, continued fragmentation of forest habitats may result in disjunct patches so small they cannot support a species that would otherwise find the habitat suitable. Rosenberg and Raphael (1986)found that at least eight species of amphibians (2), reptiles (21, and mammals (4) were significantly less abundant in stands el0 ha in size than in larger stands. Some of these (e.g., western gray squirrel) were not listed in this study among the sensitive species (table 41, but the effects of habitat fragmentation may nonetheless be cause for concern. A third assumption is that young forested stands (pole, sawtimber) in this study represent young stands of the future. Naturally occurring pole and sawtimber stands contain some large Douglas-fir stems and a substantial amount of standing and downed wood (table 1).If future management activities result in fewer large live trees, snags, and downed logs, the abundance of vertebrates associated with these habitat components may also decline. In this case, responses of vertebrates to forest management may be more extreme than those projected. The overall trend is for increased abundance among species of southern affinity that are associated with open, drier habitats in other parts of their ranges, and decreased abundance among species of boreal affinity that are primarily associated with moist coniferous forest throughout their ranges. Furthermore, most of the increasers are widespread species with large distributions that include many nonthreatened habitats. In contrast, the decreasers are almost all species with rather restricted total ranges, most of which are in threatened habitats. Therefore, even though total numbers of increasers and decreasers are nearly equal, the effects of old-growth reduction should not be viewed as neutral. Bccause many of the decreasers are affected by soil moisture and other microclimatic conditions, management to protect stream edges, moist ravines, and other moist sites may provide refuges for species that can later recolonize maturing stands. Management efforts to retain (or recreate) natural components of regenerating stands, such as hardwood understory, snags, and logs, may help mitigate against wildlife losses in future forests. It is not stand age, per se, but the structural characteristics of forests sf various ages that are important to survival of most species. Finally, results of this study address another important forest management issue in the northwest; What should managers use as a baseline for evaluation of impacts: historic or present conditions? It is apparent that many species are presently much less abundant compared with historic numbers (fig. 2). Additional reductions because of continued timber harvest will cause further declines in some species but most major declines have already occurred. Therefore, I believe that estimates of historic populations should be used as baselines for monitoring biological diversity, rather than present populations. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Field studies were funded by the Pacific Southwest Region and the Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station of the USDA Forest Service and by the University of California, Agricultural Experiment Station 3501 MS. I especially thank my field assistants (Paul Barrett, John Brack, Cathy Brown, Christopher Canaday, Lawrence Jones, Ronald Lavalley, Kenneth Rosenberg, and Cathy Taylor) for their dedication and blisters; R. H. Barrett, C. J. Ralph, and J. Verner for their support; Bruce G. Marcot for freely sharing information from his studies and for valuable discussions; and Kenneth V. Rosenberg, Fred B. Samson, and Hobart M. Smith for their commen ts on an earlier draft of this manuscript. LITERATURE CITED Barrett, Reginald H. 1983. Smoked aluminum track plots for determining furbearer distribution and abundance. California Fish and Game 69:188-190. Burgess, Robert L., and David M. Sharpe. 1981. Forest island dynamics in man-dominated landscpates. Springer-Verlag, New York. 310 p. Brown, James K. 1974. Handbook for inventorying downed woody material. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report INT-16.24 p. Bury, R. Bruce, and Martin G. Raphael. 1983. Inventory methods for amphibians and reptiles. p. 426-419. In J. F. Bell and T. Atterbury (eds.). Renewable Resource Inventories for Monitoring Changes and Trends. College of Forestry, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. Campbell, H. W., and S. P. Christman. 1982. Field techniques for herptofaunal community analysis. p. 193-200. In N. J. Scott (ed.). Herpetological Communities. USDI Fish and Wildlife Service Wildlife Research Paper 13.239 p. Frank Ernest C., and Richard Lee. 1966. Potential solar beam irradiation on slopes. USDA Forest Service Research Paper RM-18. Harris, Larry D., Chris Maser, and Arthur McKee. 1982. Patterns of old growth harvest and implications for Cascades wildlife. Transactions of North American Wildlife and Natural Resource Conference 47:374-392. Laudenslayer, William F., Jr., and William E. Grenfell, Jr. 1983. A list of amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals of California. Outdoor California 44:5-14. Marcot, Bruce G. 1984. Habitat relationships of birds and younggrowth Douglas-fir in northwestern California. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University; 282 p. Ph.D. dissertation. Meslow, E. Charles, Chris Maser, and Jared Verner. 1981. Oldgrowth forests as wildlife habitat. Transactions of North American Wildlife and Natural Resource Conference 46:329-344. Raphael, Martin G. 1984. Wildlife diversity and abundance in relation to stand age and area in Douglasfir forests of northwestern California. p. 259-274. In Meehan, W. R., T. T. Merrell, Jr., and T. A. Hanley (tech. eds.). Fish and Wildlife Relationships in Old-growth Forests: proceedings of a symposium (Juneau, Alaska, 12-17 April 1982). Bookmasters, Ashland, Ohio. Raphael, Martin G. 1987. Wildlife tanoak associations in Douglas-fir forests of northwestern California. p. 183-189. In Plumb, T. R., N. H. Pillsbury, (tech. coord.). Proceedings of the Symposium on Multiple-Use Management in California's Hardwood Resources; November 12-14,1986, San Luis Obispo, CA. General Technical Report PSW-100. Berkeley, CA: Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, 462 p. Raphael, Martin G., and Reginald H. Barrett. 1981. Methodologies for a comprehensive wildlife survey and habitat analysis in old-growth Douglas-fir forests. Cal-Neva Wildlife 1981:106-121. Raphael, Martin G., and Reginald H. Barrett. 1984. Diversity and abundance of wildlife in late successional Douglas-fir forests. p. 352360. In New Forests for a Changing World. Proceedings 1983 Convention of the Society of American Foresters. 650 p. Raphael, Martin G., and Kenneth V. Rosenberg. 1983. An integrated approach to inventories of wildlife in forested habitats. p. 219-222. In J. F. Bell and T. Atterbury (eds.). Proceedings, conference on renewable resource inventories for monitoring changes in trends. Corvallis, Oregon, 1983. Raphael, Martin G., Kenneth V. Rosenberg, and Bruce G. Marcot. In press. Large-scale changes in bird populations of Douglas-fir forests, northwestern California. Bird Conservation 3. Raphael, Martin G., Cathy A. Taylor, and Reginald H. Barrett. 1986. Sooted aluminum track stations record flying squirrel occurrence. Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station Research Note PSW-384. Rosenberg, Kenneth V., and Martin G. Raphael. 1986. Effects of forest fragmentation on wildlife communities of Douglas-fir. p. 263-272. In Verner, J., M. L. Morrison, and C. J. Ralph (eds.). Modeling habitat relationships of terrestrial vertebrates. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI. Scott, J. Michael, Blair Csu ti, James D. Jacobi, and John E. Estes. 1987. Species richness-a geographic approach to protecting future biological diversity. BioScience 37:782-788. Taylor, Cathy A., and Martin G. Raphael. 1988. Identification of mammal tracks from sooted track stations in. the Pacific Northwest. California Fish and Game 74:4-11. Vogt, R. C., and R. L. Hine. 1982. Evaluation of techniques for assessment of amphibian and reptile populations in Wisconsin. p. 201217. In N. J. Scott, (ed.). Herpetological Communities. USDI Fish and Wildlife Service Research Report 13,239 p. Appendix Common and scientific names of vertebrates mentioned in text (nomenclature follows baudenslayer and Grenfell (1 983)). Salamanders Northwestern salamander ........................ Ambystoma gracile Pacific giant salamander .......................... Dicamptodon ensatus Olympic salamander .................................. Rhyacotriton olympicus Rough-skinned newt ..................................Taricha granulosa Del Norte salamander ................................Plethodon elongatus h s a tina ........................................................ Ensatina eschscholtzi Black salamander ........................................Aneides flavipunctatus Clouded salamander .................................. Aneides ferreus Frogs and toads Tailed frog .................................................... Ascaphus truei Western toad ................................................ Bufo boreas Pacific treefrog ............................................ Hyla regilla Foothill yellow-legged frog ......................Rana boylei Bullfrog ........................................................ Rana catesbeiana Turtles Western pond turtle .................................. Clemmys marmorata Lizards Western fence lizard .................................. Sceloporus occidentalis Sagebrush lizard ........................................ Sceloporus graciosus Western skink .............................................. Eumeces skiltonianus Southern alligator lizard .......................... Gerrhonotus multicarinatus Northern alligator lizard .......................... Gerrhonotus coeruleus Snakes Rubber boa .................................................. Charim bottae Ringneck snake ............................................ Diadophis pnctatus Sharp-tailed snake ...................................... Phyllorhynchus decurtatus Racer .............................................................. Coluber constrictor Gopher snake .............................................. Pituophis melanoleucus Common kingsnake .................................... Lampropeltis zonata Common gartersnake .................................. Thamnophis sirtalis Western terrestrial gartersnake ................Thamnophis elegans Western rattlesnake .................................... Crotalis viridis Mammals Pacific shrew ......................................... Sorex pacificus Trowbridge's shrew ....................................Sorex trowbridgii Shrew-mole .................................................. Neurotrichus gibbsii Coast mole .................................................... Scapanus orarius Allen's chipmunk ........................................ Tamias senex Western gray squirrel ..................................Sciurus griseus Douglas' squirrel .......................................... Tamiasciurus douglasii Northern flying squirrel ............................ Glaucomys sabrinus Deer mouse ................................................. Peromyscus maniculatus Brush mouse ..................................................Peromyscus boy1ii Pinyon mouse .............................................. Peromyscus truei Dusky-footed woodrat ................................ Neotoma fuscipes Western red-backed vole ............................ Clethrionomys californicus Red tree vole ................................................ Arborimus longicaudus California vole ........................................ Microtus califomicus Creeping vole ................................................Microtus oregoni Western jumping mouse ............................ Z a p s princeps Coyote .......................................................... Canis Iatrans Gray fox ......................................................... Urocyon cineremrgenteus Black bear ......................................................Ursus americanus Ringtail .......................................................... Bassariscus astutus Raccoon ......................................................... Procyon lotor Fisher ............................................................. Martes pennanti Ermine ............................................................ Mustela erminea Western spotted skunk .............................. Spologale gracilis Striped skunk ................................................Mephitis mephitis Bobcat .......................................................... Lynx rubs