Human Behavior and Recreation Habitats: Conceptual ...

advertisement

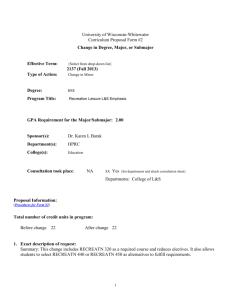

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Human Behavior and Recreation Habitats: Conceptual Issues 1 2 Donald R. Field, Martha E. Lee, and Kristen Martinson Abstract.--Individual recreation behavior and recreation experiences are more often than not determined by three sets of factors: the social group within which an individual participates, including the mix of social groups occupying a specific recreation place; the biological or physical characteristics of that place; and the management prescriptions applied there. Few studies have examined recreation behavior in the context of these three sets of factors. The present paper provides a conceptual framework to do so. The focus is upon human behavior and recreation habitats. Human ecological principles, along with concepts used to classify recreation "habitats" according to the recreation opportunities they provide, form the conceptual framework for the presentation. INTRODUCTION Human behavior in recreation areas is largely a representation of culture, human experiences, the social group associated with the present recreation event, and conditions under which the current recreation event takes place. For some the above statement may strike a cultural deterninistic cord. While not intended, the statement is made to reinforce the position that each of us has cultural baggage which frames our view of the world and guides the experiences (recreation and non-recreation) that we have. When a recreation group arrives at a recreation site, this cultural baggage will assist in the human adaptation to the facilities present, (management prescriptions) and the biological, physical, and social environments. The purpose of the present paper is to describe a conceptual framework which acknowledges the interplay of human culture, social groups, and natural resource systems in defining human behavior at a recreation site. This framework is based upon human ecology and incorporates a recreation planning and management perspective called the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS). The conceptual framework emphasizes the creation of leisure settings from the blending of human behavior (culture and social organization) with recreation places, the management system described by the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS). The benefits of our approach yield both a more holistic understanding of people, the dimensions of human behavior in recreation environments, and an understanding of management options for monitoring a recreation system, measuring human response to management actions, and resolving social conflicts and human impacts on the environment. This framework is guiding our research on recreation behavior associated with the riparian zone. Our research is beinR conducted at the Whiskeytown Unit of the Whisketytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area. 1 Paper presented at the First North American Riparian Conference (Tucson, Arizona, April 16-18, 1985). 2 The paper is part of a human resource inventory project at the Whiskeytown Unit of the Whiskeytown, Shasta, Trinity N.R.A. Funds for the project provided by the Science Division, Western Region, National Park Service, through a Cooperative Agreement (Subagreement No. 5) to Oregon State University, College of Forestry. DEFINING A CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 3 Donald R. Field is Senior Scientist, National Park Service, Coop. Park Studies Unit and Professor, College of Forestry; Marty Lee is Research Associate, Dept. of Resource Recreation Management and NPS Coop. Park Studies Unit; and Kristen Martinson is Research Assistant, NPS Coop. Park Studies Unit, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 227 Human ecology shares its development with plant and animal ecology, geography, sociology, anthropology, and demography. Each discipline has helped to refine the definition and relationship of people to their environment incorporated within the human ecological paradigm. Human ecology will not be defined here. There are excellent state- ments about human ecology such as Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure (Hawley 1950), Social Morphology and Human Ecology, (Schnore 1958), and Land Use in~ral Boston, (Firey 1947). The history Of human ecology as a field of study is well described in Urban Patterns: Studies in Human Ecology (Theodorson 1982). Recent work such as The Ecological Transition (Bennett 1976) and o;e-rshoot (Catton 1982) reaffirm the basic tenants of the theory and relationship of people, human behavior and natural resources. recreation place into a social environment. Here language and equipment together provide guidance to one's ability to enter and become part of the social world. Family reunions in Olympic National Park's Klaloch campground each year likewise reflect the conversion of a recreation place into a social environment where social meanings of family togetherness reinforce the commitment of multiple generations of the same family to each other. The sociql environment is a family gathering, the campground a backdrop for the actjvities occurring. Campsites and rules are modified by family members to ensure that a social environment for the family is secured. Nonfamily entering this camping loop soon learn there are other more accommodating campsites down the road. Lee~s (1972) description of an ethnic group's definition of a park and subsequent visit hinges on the ability of these people to create a social environment consistent with their values and definition of resources within the park they are visiting. Recent work by Edgerton (1979) illustrates how some biological/physical environments such as beaches can simultaneously accommodate drug dealing and use, courtship, family activities and picnics, nude bathing, and games of sport. Visitors include blacks, hispanics, whites, gay families, single parent families, two-parent families, teenagers, retired adults, and representatives of the baby boom generation. Social environments for each are established usually without interference from another social environment. For our purpose the key to the ecological perspective is as follows: a. The framework acknowledges humankind as part of the natural world. b. The interconnectedness of behavior and environment is depicted by the human ecosystem. c. All human interrelationships are social with culture and biotic components inseparable in analysis. d. Social and ecological change is acknowledged as having ramifications for all components of the system. e. The unit of analysis is community structure/social structure. The application of the human ecology theory to recreation behavior has been made (Machlis et a1. 1981), but further elaboration is appropriate. Human ecology stresses the interplay of homo sapiens and natural resource systems. The environmental basis for social organization is a central issue for human ecologists and is especially important for those of us studying recreation behavior in parks and forests. In every recreation situation both managment and the visitor are in their own way molding or creating a social environment. Sometimes these social environments are similar, in other cases not. Ecological descriptions of social environments have led to the description of the contrived community (Suttles 1982), the defended neighborhood (Suttles 1972), and the rural neighborhood (Kolb 1959). A similar perspective is employed here to describe leisure settings. Leisure settings are the social environments creat-ed by people as they apply their particular brand of leisure lifestyle to a recreation place; as they transport or superimpose their culture upon a recreation place; or as they create a particular leisure or recreation experience within a recreation place (Cheek, Field and Burdge 1976). Nevertheless, social environments are created by people in the manner in which they adapt to the biophysical environment and the social meanings shared within those environments. No matter how temporary, a social order and social organization is established by people which governs the pehavior of the people present. Firey (1945) suggests culture and cultural display are key factors in the creation of these social'environments. Cultural display such as the language used by occupants, the manner of dress, the technology (i.e., beer bottles and ice cooler, backpacking or other camping gear, climbing equipment), art forms and music, to name but a few cultural objects, are all present in recreation environments. Cultural objects and symbolic values attached to places help define appropriate behavior and the kind of people who are welcome. While not the central thrust of the article, DeVall's (1973) description of mountain climbers in a Yosemite campground, for example, is representative of the conversion of a Recreation places are those "habitats"-waterhsheds, bays, shorelines, picnic areas, campgrounds, parking lots, roadside pullouts, restaurants, subalpine meadow campsites, lake campsites, etc., created in part by a land management agency, accommodating human use. These places may have intended recreational value given by management, but until people occupy and adapt to the space provided, social environments or leisure settings do not occur. There can be numerous recreation places within designated recreation areas such as national parks and forests, just as there can be numerous leisure settings established within and among recreation places. The recreation place people choose to visit can influence and somewhat define the activities they choose as well as the behavior and subsequent experiences that may occur there. The recreation place and its potential influence on recreation experiences is the focus of the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS). ROS is a framework 228 recreationists can pursue a variety of activities (social and physical), recreation managers can provide for the widest possible achievement of desired experiences. for understanding the relationship between recreation experiences and the environment. ROS defines a range or spectrum of recreation opportunities ranging from primitive to urban that land managers can provide to meet a diversity of visitor preferences (Buist and Hoots 1982). This concept is based on the assumption that quality in outdoor recreation is best assured by providing a diversity of recreation opportunities (Clark and Stankey 1979), an idea suggested in early research on recreation users (e.g., Shafer 1969; Wagar 1966; King 1966). Operationalized, ROS is a system which enables public or private recreation managers to inventory and classify land and water areas according to their capability to provide recreation "potential" as defined within the agency guidelines. Both the USDA Forest Service and USDI Bureau of Land Management have adopted a planning system (Recreation Opportunity Planning) which uses the ROS to inventory and manage their recreation resources (Buist and Hoots 1982). Though ROS can be used by land managers to describe what a particular recreation place is like and what visitors might expect to find there, it cannot describe or predict an individual or group's choices, behavior, or subsequent experiences that will occur at a particular recreation place (Clark 1982). Figure 1 describes the relationship between people, culture and human behavior and the bio/ physical environment. In addition, it i llustrates that recreation places are provided by management and that leisure settings result from the joint interaction of people, culture and those recreation places. REVIEW OF LITERATURE The literature on water-based recreation which addresses the interaction of human behavior and bio/physical environment is limited. Social science research on waterbased recreation has, however, generated several key findings which support the conceptual framework we have outlined. The focus in ROS is on the recreation place. The variety in types of recreation places an area provides represents the choices people have when considering outdoor recreation opportunities. ROS recognizes that the experiences derived from recreation are related to the places or locales in which they occur but are not determined by them (Clark and Stankey 1979). Recreation opportunity places, as described by ROS, are composed of three primary elements: the physical attributes--natural features such as vegetation, bodies of water, and topography; the social environment--the numbers and types of people and activities present; and the management prescription--the level and types of development, rules, and regulations provided by managers (Clark and Stankey 1979; Stankey and Brown 1981). These elements, existing in various combinations, can be used by managers to provide diversity in recreation opportunities. It is these elements over which they have most control. By offering a variety of "combinations" of such elements where Leisure activities oriented around water resources make up a considerable portion of all recreation participation. "Water is probably the greatest of all outdoor recreational attractions" (Lime 1975). People seek out water resources not only for direct recreational use such as swimming or boating but also as an aesthetic background for non-water oriented activities. A study of water-based recreation by residents in western Washington, western Oregon, and northern California identified that activities of observing nature, visiting the beach, and beachcombing comprised a large percent of all wateroriented recreation (Field and Cheek 1974). Recreation Places Recreating Individuals and Groups ---.,. The unique qualities of people, their culture and recreation techno 1ogy influence the manner in which individuals and groups adapt to a recreation setting. Figure 1. - The types of recreation places found within a designated recreation area comprise the range of recreation opportunities represented within the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS). The relationship of people and recreation places for creating leisure settings. 229 In general, because of the secluded nature of river ways, many users prefer and expect few encounters with other groups while traveling on the river, particularly in wilderness areas (Schreyer et a1. 1976, Shelby and Nielsen 1975, Heberlein and Vaske 1977, Tarbet et al. 1977). Most river systems provide considerable screening from other river users due to winding channels, thick bank vegetation, and often steep, narrow corridors. There may be several groups floating a particular waterway who would not see each other all day if they were traveling at the same speed and sufficiently separated for the particular setting. However, for a visitor who is stationary, such as a fisherman on the bank, contacts with floaters could be numerous because the river would continually bring groups into and out of view (Heberlein and Vaske 1977). Location of Use Water-based recreation occurs in a variety of different places and includes a wide range of activities. Water resource areas may differ considerably in setting attributes but they all have the common characteristic of water. Consequently, an activity such as swimming can be common among the most diverse resource settings and it is erroneous to assume that such activities are area-specific (i.e., kayaking only on rivers or swimming only at the beach) (Field and Cheek 1974). It is interesting, however, to note some general trends. McDonough and Field (1979) identified the distribution of outings among water resources in a survey of Washington residents. Lakes received considerably more use than any other water resource type. Reservoirs, followed by rivers, were the next most often used areas. A small percent of outings occurred at the ocean. The most common activities occurring at each of these areas were also identified. Swimming, powerboating, sailing, canoeing, and fishing all occurred primarily at lakes, followed by reservoirs in considerably smaller percentages. Beachcombing also took place most often at lakes, followed closely by the ocean. Lakes and reservoirs do not provide as much screening from other users as do river ways. Thick vegetation may provide seclusion from other groups around the shoreline but the nature and shape of lakes provide prime exposure of most users on the water and on opposite shores. Lakes and reservoirs can often provide opportunities for a wider variety of activities than rivers or ocean beaches. Common activities include swimming, fishing, waterskiing, powerboating, sailing and canoeing. McDonough (1980) found that primary reasons for visitors choosing to recreate at a lake resource were presence of friends, proximity, solitude, and water quality-pursuit of specific activities being less important. Recreation Places and Water Resources There are essentially three types of water resources based on their characteristics: rivers and streams (running water), lakes and reservoirs (standing fresh water), and beaches adjacent to oceans or large lakes. Differences in resource attributes, such as screening from other users due to topography or vegetation, give rise to differences in social norms dictating appropriate types and amounts of use. A variety of activities take place at all water environments though some are unique to a particular setting (e.g., surfing at the ocean) and obviously some water resources are more conducive to particular activities than others. McDonough (1980) points out in her study of lake users that though activity is a primary reason for choosing a specific place to recreate, there are many other influencing factors. Differences and similarities in activities are examined for each of the three water resource types. Beaches are water oriented recreation places, often with irregular shorelines and open spaces that accommodate a wide variety of use. Beaches are popular environments for both water and nonwater recreation activities, with many users spending the majority of their visit out of the water. Common recreation activities include surfing, sail boarding, swimming, boating, sunbathing, team sports (e.g., volleyball or football), kite flying, and beach combing. Visible evidence of management activities (e.g., lifeguards or food concessions) are often more acceptable at beaches than at other water settings. People visiting beaches often expect to encounter others, and in fact, some social groups depend on density of use to secure privacy, while others seek the outside contacts that beaches may provide (Hecock 1970). A wide variety of social groups visit beach areas, and of the three water settings, beaches are where one would most likely find individuals recreating alone. Common activities on rivers and streams include fishing, tubing, river running, and swimming. T,he definition of any one of these activities, as with most recreation activities, may vary considerably depending on the degree of individual involvement. A single activity such as fishing can actually consist of a continuum of involvement levels ranging from generalized participation to specialized style (Bryan 1977). Fly fishing for trout in a high mountain stream and bait fishing for salmon in a coastal river are very different activities. This variation within any one activity must be kept in mind when generalizing about river or any water resource use. SUMMARY Understanding the relationships between behavior, culture, leisure lifestyle and recreation places is an important step in recreation research. There has been considerable research done on specific aspects of recreation behavior, but little which attempts to understand the joint interaction of behavior and habitat. Indeed, the 230 social organization of leisure behavior in parkP and forests is as complex and sophisticated as the social organization of an urban neighborhood. King, D. A. 1966. Activity patterns of campers. USDA For. Ser. Res. Note NC-18. Kolb, J. 1959. Emerging Rural Communities: Group Relations in Rural Society. Univ. of Wisconsin Press, Madison. Lee, R. 1972. The social definition of outdoor recreation places. Pp. 68-84 in Social BP.havior, Natural Resources and the Environment. Edited by William Burch, JR., Neil H. Cheek, Jr. and Lee Taylor. Harpers Row, New York, New York. Lime, D. 1975. Backcountry river recreation: Problems and research opportunities. Naturalist 26(1):2-5. Machlis, G. E., D. R. Field, and F. L. Campbell. 1981. The human ecology of parks. Leisure Sciences 4(3):195-212. McDonough, M. H. 1980. The influence of place on recreation behavior: The case of northeast Washington. Ph.D. Dissertation, Univ. of Washington, Seattle. McDonough, M. H. and D. R. Field. 1979. Coulee Dam National Recreation Area: Visitor use patterns and preferences. NPS Univ. of Washington, Seattle. Schnore, L. 1958. Social morphology and human ecology. American Journal of Sociology 63(May):620-24, 629-34. Schreyer, R., J. W. Roggenbuck, S. F. McCool, L. E. Royer and J. Miller. 1976. The Dinosaur National Monument whitewater river recreation study. Institute for the Study of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, Utah State Univ., Logan. Shafer, E. L., Jr. 1969. The average camper who doesn't exist. USDA For. Ser. Res. Pap. NE142. Shelby, B. and J. M~ Nielsen. 1976. Use levels and crowding in the Grand Canyon: River contact study. Final Report Part III. Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona. Stankey, G. H. and P. J. Brown. 1981. A technique for recreation planning and management in tomorrow's forests. Pp. 63-73 in Proceedings XVII IUFRO World Congress, Japan. Suttles, G. D. 1972. The Social Construction of Communities. Univ. of Chicago, Chicago. Suttles, G. D. 1982. The contrived community: 1970-1980. Pp. 224-230 in Urban Patterns: Studies in Human Ecology, George Theordorson. Penn. State. Univ., University Park. Tarbet, D., G. H. Moeller, and K. T. McLoughlin. 1977. Attitudes of Salmon River users toward management of wild and scenic rivers. Pp. 365-371 in Proceedings: River Recreation Management and Research Symposium. USDA For. Ser. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-28. North Central For. Exp. Sta. Minneapolis, MN. Theordorson, G. 1892. Urban Patterns: Studies in Huma Ecology. Penn. State Univ. Press, University Park. Wagar, J. A. 1966. Quality in outdoor . recreation. Trends in Parks and Recreation 3(3):9-12. The conceptual framework presented here is another step in describing this human/biological picture. From here we can begin to examine related resource management issues such as assessing social impact, social conflicts and carrying capacity, and predicting visitor response to management actions. Using this perspective we can better understand the dynamic nature of various recreation places to accommodate a variety of visitors engaging in a wide diversity of activities across time and space. LITERATURE CITED Bennett, J. 1976. The Ecological Transition: Cultural Anthropology and Human Adapation. Pergamon Press, Inc. New York. Bryan, H. 1977. Leisure value systems and recreational specialization: The case of trout fishermen. J. of Leisure Research 9(3):174-187. Buist, L. J. and T. A. Hoots. 1982. Recreation opportunity spectrum approach to resource planning. J. Forestry 80(2):84-86. Catton, W. R., Jr. 1982. Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Ill. Cheek, N.H., D. R. Field, and R. J. Burdge. 1976. Leisure and Recreation Places. Ann Arbor Science, Ann Arbor, MI. Clark, R. N. 1982. Promises and pitfalls of the ROS in resource management. Australian Parks and Rec., May, pp. 9-13. Clark, R. N. and G. H. Stankey. 1979. The recreation opportunity spectrum: A framework for planning, management, and research. USDA For. Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW-98. 32 p. DeVall, W. 1973. Social worlds of leisure. Pp. 131-144 in Leisure and Recreation Places. Edited by N.H. Cheek Jr., D. R. Field, R. J. Burdee. Ann Arbor Press. 1976. Edgerton, R. B. 1979. Alone Together: Social Order on an Urban Beach. Univ. of California Press, Berkeley. Firey, W. 1945. Sentiment and symbolism as ecological variable. Am. Sociological Review 10(April):140-148. Firey, W. 1947. Land Use in Central Boston. Harvard Univ: Press. Cambridge. Field, D. and N. H. Cheek, Jr. 1974. A basis f'or assessing differential participation in water-oriented recreation. Water Resources Bulletin 10(6):1218-1227. Hawley, A. 1950. Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure. The Ronald Press, New York. Hecock, R. D. 1970. Recreation behavior patterns as related to site characteristics of beaches. J. of Leisure Research 2(4):237250. Heberlein, T. A., and J. J. Vaske. 1977. Crowding and conflict on the Bois Brule River. Water Resources Center Tech. Rep. WIS WRC 77-04. Madison, Wise. 0 231