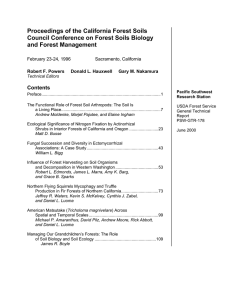

INFLUENCE OF FIRE ON FACTORS THAT AFFECT SITE PRODUCTIVITY Roger D. Hungerford

advertisement