Contextualized Teaching & Learning: A Faculty Primer

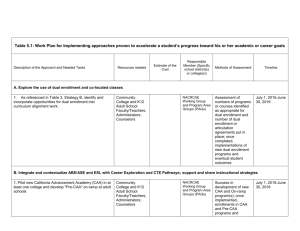

advertisement