Moving Districts Forward: Examining Differences in Teachers’ Beliefs about... Paul Fitts, M.S.Ed., & Robert J. Dixon, Ph.D., NCSP

advertisement

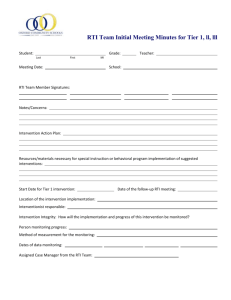

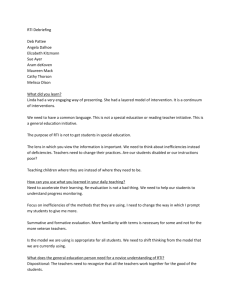

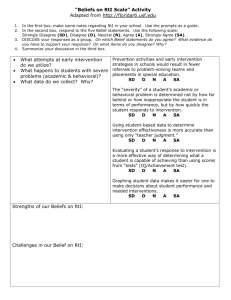

Moving Districts Forward: Examining Differences in Teachers’ Beliefs about Behavior Paul Fitts, M.S.Ed., & Robert J. Dixon, Ph.D., NCSP University of Wisconsin-La Crosse Abstract Method As schools move forward to implement Response to Intervention (RtI), some districts are focusing on academics while others are focusing on behavioral concerns. System change is a complex process that begins with teachers’ beliefs and practices. This study will examine the impact of perceived RtI supports in a school with teacher experience to determine differences in classroom beliefs about behavior management practices. Implications to educators and school psychologists impacting system change will be discussed. Instrumentation: • Teachers completed the Beliefs about Behavior-II survey designed to reflect current behavior management beliefs (Wright & Cook, 2010). • Teachers were also administered the REACh survey designed to identify perceived level of RtI practices present in their school. • Questions were posed to identify teachers conceptions of what RtI practices are, the next logical step in RtI implementation, and the areas of behavioral management in which training would benefit them. Data Analyses: • A median split was completed to determine if teachers’ behavioral beliefs (BAB II) vary depending on the level of RtI practices they perceive to be present in their school of practice (REACh). • The independent variable is perceived level of RtI present and the dependent variable is beliefs about behavior. Introduction Background: • No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, 2002) and the 2004 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) have established the expectations for change (Glover & DiPerna, 2007). • Many districts are making steps towards or have implemented a Response to Intervention (RtI) system in reaction to the new educational climate. • Most models of RtI include an academic component and a behavioral component; the later is the focus of this study. • Implementation of an RtI system is a complicated process due to the fact that no two schools are equal in every way and all rely on a complicated social system of teachers with different strengths and weaknesses implementing the change (Cutis, Castillo, & Cohen, 2010). • For this reason, it is critical for school psychologists and administrators who seek system change to understand educator’s perceptions of existing RtI practices within their school and their beliefs about behavior management that may or may not coincide with the RtI conceptualization of behavior management. Study purpose: • This study seeks to determine the differences in behavior management beliefs based on a teacher’s perceptions of the current RtI practices present in a school. • This study will make an addition to the literature on system change by identifying teachers beliefs on RtI and behavioral management practices which may or may not be consistent with RtI implementation. • It will compare statistical methods for attaining a staffs beliefs. • With the knowledge of teachers’ beliefs about behavioral management and RtI practices, administrators and school psychologists can work towards informed system change. Results • The reliability of each measure this study used as well as the mean score and standard deviation can be found in Table 1. • As a result of the median split, scores of 35 and up are teachers who had a strong belief that RtI was implemented in their school (RtI Strong). • Scores of 34 and below are considered to be teachers who do not see their schools practices as consistent with RtI (RtI Weak). See Figure 2 for a comparison of RtI Strong versus RtI Weak on beliefs about behavior. • The relationship noted between the BAB-II and REACh surveys yielded an non-significant correlation of r(30) = -.23, p = .11 Figure 1. Teacher Population Unspecified 14% High School (HS) 23% Standard Deviation 7.83 7.07 Figure 2. Effects of RtI Strong Versus RtI Weak on Beliefs About Behavior 96 Method Participants: • The current study used 30 teachers from 1 school district. The teachers practice at the Elementary school, the Middle School, the High school, and 4 were unspecified. See Figure 1 for the proportion of respondents from each school. • Out of a total population size of 116 teachers, 30 responded. The resulting response rate was 26% Mean 95.41 34.12 Beliefs 95 About 94 Behavior 93 92 91 90 RtI Strong Item Frequency Instructional Practices 16 Pre-referral problem solving 14 Associated Practices (e.g., PBIS, CPI) 8 Structural/Day Modifications 6 Assessment Practices 5 Table 3. Staff Training Suggestions For RtI Implementation Item Frequency RtI has been implemented Entire Staff Involvement Best Practices Training Intervention training Behavioral Instruction Additional Staff and professional development funding Assessment Practices Other (schedule modifications, unsure) Item Table 1. Measure Statistics Reliability .72 .89 Table 2. Current School Practices Consistent With RtI 14 12 9 6 5 5 4 3 Table 4. Training on Behavioral Management Practices Elementary School (ES) 40% Middle School (MS) 23% Measure Beliefs About Behavior II REACh Survey Qualitative Questions Four questions were developed to gain further insights into teachers beliefs on RtI and behavioral management practices, three will be analyzed. 1) What are the current school practices in place that you feel are consistent with RtI practices? See Table 2 for the frequency of responses. 2) Given what you know about Response to Intervention and your school, what would be the next logical step in professional development to move forward with implementation? See Table 3 for the frequency of responses. 3) If you could receive training on one aspect to improve your behavior management practices in the classroom, what would it be? See Table 4 for a listing of the frequency of responses. RtI Weak Frequency PBIS practices Motivation interventions Unsure Tier 3 interventions Use of reinforcements Improved practices (assessment, instructional, PLC’s) Specific interventions (organization, oppositional students) 7 6 6 4 4 3 2 Discussion • There was a qualitative difference in teachers’ opinions within the same district and school for RtI practices that have been implemented. This can be categorized as: 1. Individualistic: Reflecting a teacher’s own classroom implementation of RtI within an area that he/she can control. 2. Systemic: Reflecting a school-wide perspective that spans what is happening across classrooms with the implementation of RtI. • Implication: future studies need to be very explicit for the reference point for teachers to comment on RtI practices in the school. Discussion • There was a general perception among school personnel that RtI is already being implemented. However, additional comments expose a basic confusion amongst the staff in regards to RtI practices in four areas: 1. Interventions focused only on using existing resources; e.g., using Title 1 services for interventions. 2. Problem solving used only to determine interventions or special education eligibility; i.e., no examination of universal curriculum. 3. Assessment practices focused on diagnostic or problem-focused practices; e.g., no universal screening. 4. Practices focused on people not systems of response; e.g., “I think Rosemary is doing a great job at RtI” • Implications: there did not appear to be a common language to describe or understand what is happening in the schools in reference to RtI. This would go beyond the “knowledge of the triangle” and describe practices in the classroom or school that are examples or non-examples of RtI. Knowledge of this confusion could help coaches to target their mentoring of teachers in a sustained effort at systemic change toward a functional knowledge of RtI. • Contrary to hypothesis, there was no significant relationship between teacher beliefs of behavior and school practices consistent with RtI. • Limitations • Sample size was small and spanned multiple academic levels. It may be beneficial to examine a larger sample at one level. • Surveys, while reliable, may need to have additional validity studies to reflect school reforms consistent with RtI and behavior practices. • Future studies may benefit from further investigating the confusion aspect observed in this study. Similar qualitative questions could be compared with observations of the schools model of RtI in practice. Summary, Implications, and Conclusions • System change is complicated by teacher beliefs and actual practices. A school psychologist may help a district move forward by: 1. Training school staff with targeted and specific examples of RtI. 2. Engaging the staff in resource mapping designed to not only identify existing services, but also to identify gaps that need attention. 3. Establishing a coaching or mentoring system with teachers to assist in the sustained implementation of practices consistent with RtI. References Browning-Wright & Cook. (2010). Beliefs about Behavior, 2nd Edition. Sierra Madre, CA: Educational Consulting Services Curtis, Castillo, & Cohen. (2010). Best Practices in System-Level Change. In Thomas & Grimes, Best Practices in School Psychology V (pp. 887-901). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists. Daigan, Ring, Volpansky. (nd). Data-Based Decision Making: A Guide to Performing a Comprehensive Framework Appraisal. Madison, WI: Department of Public Instruction Glover & Di Perna. (2007). Service Delivery for Response to Intervention: Core Components and Directions for Future Research. School Psychology Review, 36, 526-540. Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004. Pub. L. No. 108,446 No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. Pub, L. No, 107-110, 115 Stat. 1425 Wright, J. (2011). Reaching a Positive 'RtI Tipping Point': Tips for Schools." retrieved from interventioncentral.org