..« ... C.M.

advertisement

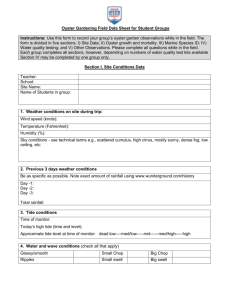

..«... ..... ..", International Council ror the . Exploration of the Sea StatutOl-y Meeting~. C.M. 19931F:27 Mariculture Committee -------------------------------------------~- ~~~--~_._------------------------------------------- Introductions of exotic species associated with Pacific oyster transfers from France to Ireland. D. Minchin, C.B. Duggan, J.M.C. Holmes* & S. Neiland. Fisheries Research Centre, Department of the Marine, Abbotstown, Dublin 15, Ireland. :' * Natural History Division, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, . Dublin 2, Ireland. • SUMMARY Following the implementation of EC Council Directive 91/67/EEC, the free movement of trade in shellfish commenced in January 1993. This Directive permitted transfers of Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas, which previous Irish legislation had controlled. Importations from France took place from January 1993. All importations were certified as being free from Bonamia and Martelia and also free from other species. Sampies from consignments revealed the presence of Mytilicola orientalis, Myicola ostrea, Crepidula fornicata, Ostrea edulis and Mytilus edulis. The biomass of the importations and the frequency of M. orientalis and M. ostrea in these consignments suggest that they may become established in Irish waters and that there was a risk, albeit smalI, of introducing pathogens associated with these species in Irish relaying areas. Oysters sourced from Marennes-Oleron had other exotic species present. INTRODUCTION Until the end of 1992 Ireland had a policy of banning all mollusc importations except under licence. Transfers from inspected sites in Norway, Great Britain and Guernsey have been permitted. This policy rela~es to Ireland being an Island and so in a position to exclude pests as weil as invertebrate and fish diseases. However some introductions are already known as a result of shellfish transfers, such as Crepidula fornicata (Minchin et al., in press - no live populations or specimens of . ..... "-'" ...... -. '_.... -,... .. . . " . - ~"- •• ' • . . . . . . . -8 ' '". ~ ••• ----.. . ... . , this species in Ireland are known to exist sin'ce 1963), Calyptraea chinensis (Minchin et a/., 1987) and shell disease of the oyster Ostrea edulis (Duggan - internal report, 1963). These introductions tagether with outbreak of various oyster dis~ases in Europe led to the strict control of all importations to Ireland, despite wh ich an illegal importation of the oyster Ostrea edulis lead to the establishment of Bonamia ostrea disease in Cork Haroour, Gaiway Bay and possibly in Clew Bay. Once the disease was identified~ restrietions on ttie transfer of oysters thoughout Ireland were imposed, movements being permissable only under Iicence. The disease-free status of Ireland was compromised by Bonamia and shellfish exports from Ireland were impeded. The implementation of the EC Directive on trade in shellfish is Iikely to compromise shellfish cultivation in Ireland furttler with the eventual establishment of non-native flora and fauna which are Iikely to interact with Irish marine communities. Exotic species such as Crassostrea gigas, Ruditapes semidecussataj Haliotus discus hannai, Ha/iotus tubercu/ata, had all been successfully introduced into Ireland using the ICES Code of Practice so that the introduction of pests, parasites and diseases were avoided. In all cases introductions were made through quarantine. The most recent introduction of the Japanese scallop, Patinopecten yessoensis (in 1990) was under tighter controls as the ICES Code of Practice had been updated. Future intended introductions of exotic commercial species will continue to be subject to the tull protocol~o! the currerit iCES Code of Practice. METHODS Oysters imported trom France were selected either trom oyster bags removed trom different parts ot the consignment during unloadingi or as sampies received trom growers or from trestles on the shore. Oysters wereweighed and measured and the trequency of associated species . tound in the gut (Mytilico/a orienta/is Mori, 1935 identitied using Ho & Kim, 1992), or attached to the gills or within the shell cavity (Myico/a ostreae Hoshima & Sugiura, 1953 identified using Ho & Kim 1991) cr on the shell surtace (Crepidu/a fornicata (L.) and Ostrea edu/is L.). Other associated organisms were also removed. Sampies were obtained trom different regions within the country to wh ich consignments were known to have been dispatched. Dinoflagellate cysts were found in sediment within the valves of dead oysters associated with oysters transterred in January 1993 and are discussed elsewhere (O'Mahony, 1993). These had been kept in a cold room for same weeks prior to examination . . ..' ." .. .,' , ", RESULTS The first known importation was to Cariingfora on 23 January 1993, of half grown oysters from the Marennes-Oleron region in Freince. Their conaition was very poor, they heia translucent flesh, a very reduced digestive gland and many were gapirig and had long narrow shells. Subsequent consignments were of marginally better quality. All sampies demonstrated varying frequencies of associated exotics (Table 1). The regions where oyster reiayings have taken place are shown in Figure 1. Up to 10M. orientalis were found in the gut of an oyster. When present in m.imbors these produced a pea-size swelling of the rectum and the female copepods were easily seen through the Iining of the gut. , Specimeris were orange/pink in coloratiori. Infestation frequencies varied greatly between sampies. Those iriüoduced to Carlingforrl in January had an irifestation of 7.3% which haa reduced to 2.3% in March in a sampie of the same importation; the decline in the frequency corresponded with .an increase in oyster mortality over this period. Egg strings were found in ',samples taken in January and March. This species was found within :, Pacific oysters from wild settlements in t~e Oleron arid Archachon 'regions but also from nursery-raised spat, with adult female copepods and attached e9g strings being found in oysters fram ca 1g. Myicola ostreae was found either adhering to the gills, free on tlle gills or within the manile cavity. Where they wore found on tlle cream coloured gills, they were often associated with a small light oval patch; witl, up to tllree being taken from a single oyster. Two Crepidula fornicata were found attached to the shells of oysters o,riginating from Marennes-Oleron. These were both males of 6 arid 8mm shell length. The surface of many of the imported oysters haa an attached serpulid Pomatoceros sp. (Polychaeta). Sediment fram within oysters contained specimens of Tenibella lapidaria (Polychaeta), both previously unreported from Irish weiters. Marine aigae associated with oyster imjJortations were not examiried. DISCUSSION Exotic species are known to spread by ~he movement of shelifish, in particular with transfers involving oysters: Expansion of the movements of oysters following the EC Council Directive 91/67/EEC which concerns the trade in living aquaculture proaucts, ~i11 merin that there will most certainly be an expansion of the ranges of vai"ious species of flora and fauna associated with the shellfish transfers. The ICES Code of Practice for the Introduction and Transfers of species considors the transfer, not _ . ' . . . ,,,! .. only of the organism under transfer, but also of associated species. As the introductions of many shellfish species to coritinental Europe took place at a time when the ICES Code of Practice had not been fully formed, a number of species that fall into the category of pest or fouling species became established including M. orientalis and Hydroides elegans in France (His et al., 1978). Many species survived the transfer from the Pacific to Fra~ce which would have taken same days, so they are likely to survive the shorter transfer from France to Ireland. The presence of Ostrea edulis and Mytilus edulis in. consignments is of cancern. Although not quantified musseis, M. edulis, have appeared in all consignments of half-grown oysters. 80th O. edulis and M. edulis are known vectors of Martelia refringens (Tige & Raboun, 1976; Camps et al., 1975). In the case of the protozoan Bonamia ostreae the flat oyster, ..9. edulis, is a vector. Pathogens have been identified in Japanese Pacific i oysters, from whence the French introductions came. These include a :,haplosporidian (Friedman, 1991) and a herpes-Iike virus in Pacific oyster .' larvae reared in French oyster hatcheries (Nicholas et 81., 1992). There is cancern that these may spread to oyster culture areas. This rccent information questions tf:1e use of even hatchery-reared Pacific oysters being suitable for transfer for cultivation within uriinfected areas. M. orientalis was not known in Irish waters until prior to the transfer of Pacific oysters from France in 1993. This parasite is known to cause damage to the lining of the gut of the oys~er C. gigas, the mucosa being destroyed with penetration into the underJying connective tissue (Sparks, 1962), but Bernard (1969) was not able to show histological damage in his study. Grizel (1985) refers to its ab!J~ty to cause a reduction in condition index, and in severe cases to cause mortality. His et al. (1978), record mortalities of up to 50% in oyster growing areas in France. Chew et al., (1965) noted that infested oysters in the north-east Pacific were not as weil conditioned and Odlaug (1946) recorded that infested oysters lost condition more rapidly following spawning. DeslousPaoli (1981) in his study concludes that the size of the hast is important, having found M. orientalis in six-month-old Pacific oysters. He claims that in cases where three female specimens appear in a hast there is a significant decrease of rates of carbohYdr~te and glycogen production, presumably infestations greater than this'~liave ",.greater demands on the hast. One method of control proposed by Grizel is the complete prevention of transfer (Grizel, 1985). More recently, recognising that Mytilicola intestinalis can cause problems for musseis, he rind others (Blateau et al., 1992) have examined treatments to eliminate infestation levels using dichlorvos. .,..~ , e· .. ". ". '. ... '~ .. ', The cr"itical numbers of M. orientalis required to establish a population may depEmd on the local conditions to which the animals have been introduced. Enclosed inlets with poor to moderate tidal flushing are probably more likeiy to dEwelop.local populations. It is considered that Carlingford Lough may be suitable for expansion of this parasitic copepod which is known to infest oysters and musseis and trochid snaiis. Almost 50 tonnes of oysters with a 3-1 2 % infestation rate have already been relayed in Cadingford. Transfers of nursery-reared spat, are also capable of holding ovigerous female copepods. Eggs of these copepods may develop within smaller oysters once swallowed. It may be necessary to consider filtered supplies of seawater in order to avoid infestation of oysters in hatcheries. Ovigerous females were present in January and Fehruary; indicnting that in France reproduction may take plnce nll year. in Bi-itish Cohjmbia Bernard (1969) showed that reproduction takes place from June to late August and t~nt the main population of the copepod was confined to Ladysmith Harbour where the .original introductions of Pncific oysters took place. He reports that the larval stages of this species are short nnd ttley do not travel far, and lnterestingly states that •oysters rind musseis raised above the substrate are not infested. This last ~ statement wouid not appear to be borne out in the French experience 'because imported half-grown oysters had previously been cultivatcid on trestles. The related species Mytilicola intestinalis Steuer is known in Irish waters only from Galway Bay and the coastline of Co Cork (Crowley, 1972), but not from Carlingford Lough (Crowley, 1972) where niusseis were again examined in 1993 together with clams and oysters~ Korringa (1951) recorded it in Dutch waters as tlaving an adverse effect causing mortality in some cases. Theisen (1987) noted that it has a marked effect on concÜtion in the mussei, Mytilus edulis L., but although Davey (1989) found some slight reductions of musseI growth in his studies in. Cornwall, England, he conciudedthat M. edulis had no harmful impact on musseIs and that the species had features in common with a commensal. Introductions of Paciflc oysters wittl M. orientalis must have consequences for other marine populations. Ttle species is known to . occur in val-ious oysters, musseis, clams ~md trochid and cither snails and to-date there have boen no quantified studies of its effect on the'se species. It is known to have taken up new molluscan hosts in British Columbia (Bernard, 1969). Myicola ostreae is a poecilostome copepod previously known from C.gigas in Japan and Korea, and more recently in France following the . 1970's direct oyster transfers. The family, Myicolidae are mainly found on the gilis of marine bivalve molluscs. This species is also known to occur within Ostrea edulis in the Baissin d' Arcachon (His, 1977). ·. Thore is sufficient evidence to suggest that the introduction cif Crepidula fornicata can result in serious modification of trophic relationships within muddy estuaries and bays, areas where oysters and musseis are often cultivated. Successive introductions of Gonsignments containing small and relatively incorispicuous individuals, .as found in this study, could lead to the establishment of breeding populations. Since the 1920's (Spicer,1923) Ireland has been weil aware of the possibility of the introduction of C. fornicata and measures to prevent its importation were a feature of the licensing system controlling all oyster impo'rtations at that time. It does appear that, despite screening, some small populations were transferred to Clevil and Kenmare Bays following , separate and unsustained importations of oysters (0. edulis) for laying, but fortunately these did not survive. Should populations of C. fornicata become established there may be significarit changes in: (a) trophic competition, (b) changes in the texture of the sea bed, and " (c) modification of the benthos. ;In France the abundance of this species in certain bays is such that ! dredging of the sea-bed for their removal is sometimes necessary to enable management of growth of oysters vilithin the same bay (Anon, 1985). In the Grariville area of Normandy the population has increased from 150,000t in 1985 to 750,000t in 1992 (Anon,.1993). Sargassum muticum is widely distributed within oyster growing areas in France. Transfers of germlings of this phaeophyte on oysters are a poteritial risk with oyster importations. S. muticum exterided its range to the North-east Pacific at the same time aOs oyster importations and it is Iikely that they were transferred with oysters. More recently Critchley & Dijkema (1984) demonstrated a transfer of S. muticum on native oysters Ostrea edulis from The Solent in England to Yeseke, The Netherlands. This plant can be easily transferred from a small size as has been determined in experiments by Yamauchi (1984). Being a monoecious species a single plant can result in the development of a population, and can become mature within a year. Introductions of this species to Ireland are not only possible but probable with sustained transfers of oysters. According to Scagel (1956) Canadian oyster fishermen have difficulty in observing their stock beneath the extensive stands of S. muticum. 'The plants are buoyant and when attached to oysters can cause them to be transferred elsewhere. Critchley & Dijkema (1984) make an appeal at the end of their paper ..... A call is made for the rigid application of existing quarantine procedures regarding the movement of shellfish and the establishment of an international body (perhaps as part of the European Economic Community) to both administer and enforce these regulations" ... The transfers of shellfish species in the course of trade result in the transfer and establishment of exotic species. The movements of .. organisms between different biological prayinces can result in unexpected consequences • Examples of this include: the zebra mussei Dreissena polymorpha from the Black Sea to The Great Lakes (Snyder, 1992); the invasion of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi fram the eastern coast of North America to the Black Sea resulting in modifications of the plankton and elimination of some otherwise profitable fisheries (Harbison, 1993). Movements over small distances can also result in serious consequences as in the case of Gyrodactylus transferred from the Baltic Sea to Norway with salmon, Salmo salar. • Where little consideration is given to ecological consequences, in the" movement of exotic species associated with shellfish movements, serious biological consequences may be expected. The movement of half-grown Pacific oysters from France to Ireland has presently been suspended pending further discussion . ., , ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Prof. Inger Wallentinus. Drs Eric Edwards and Peter Dare for information readily provided. . REFERENCES Bernard, F.R., 1969. The parasitic copepod Mytilicola orientalis in British Columbia Bivalves. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada 26: 190-191. Blateau, D., Le Coguic, V., Mialhe, E. & Grizel, H., 1992. Mussei (Mytilus edulis) treatment against the red copepod . Mytilicola intestinalis. Aquaculture, 107: 165-169. Comps, M. Grizel, H., Tige, G., & Duthoit, J-L., 1975. Pathologie des invertebres.- Parasites nouveaux de la glande digestive des Mollusques mainis, Mytilus edulis L. et Cardium edule, L. C.R. Acad. Sc. Paris 281: 179-181. Critchley, 'Ä.T; & Dijkema, R., 1984. On the presence of the introduced brown alga Sargassum muticum attached to commercially imported Ostrea edulis in the S.W. Netherlands. Botanica Manna 27: 211-216.. Crowley, M., 1972. The parasitology of Irish musseis. Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Fishery Leaflet No. 35., 12pp. .. Korean J. ZooI., 35: 240-255. Katkansy, S.C., Sparks, A.K. & Chew, K.K., 1967. Distribution and effects of the endoparasitic copepod Mytilicola orientalis on the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Proc. Nat. Shellfish. Assoc., 57: 50-58. Ollaug, T.O., 1946. The effect of the copepod, Mytilicola orientalis upon the Olympian oyster, Ostrea lurida. Trans. Am. Microscop., 65: 311-317. O'Mahony, J.H.T. (1993) Phytolankton Species Associated with Imports of the Pacific Oyster, from France to Ireland. ICES C.M. K. Quiniou, F. & Blanchard, M. 1987. Etat de la proliferation de la crepidule (Crepidula fornicata L.) dans le secteur de Granville (Golfe Normano-Breton)-.1985. Haliotus 16: 513-526. ~Minchin, , D.; Duggan, C.B. & McGrath, D., 1987. Calyptraea chinensis (Mollusca: Gastropoda) on the west coast of Ireland: a case of accidental introduction? J. Conch., 32(5): 297-302 Nicolas, J.L., Comps, M. & Cochennec, N. 1992. Herpes -like virus infecting Pacific-oyster larvae, Crassostrea gigas. Sull. Eur. Ass. Fish Pathol., 12(1): 11. Piquion, J.-C., 1985. Lutte contre les competiteurs. Equinox, No. 3 : 27-31. Snyder, F.L., Garton, D.W. & Brainard, M. 1992. Zebra musseIs in the Great Lakes: The invasion and its implications. The . Ohio State University. 4pp Scagel, R.F., 1956. Introduction of a Japanese alga, Sargassum muticum into the north-east Pacific. Fisheries Research papers, Washington Department of Fisheries 1: 49-59. Sparks, A.K., 1962. Metaplasia of the gut of the oyster Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg) caused by infection with the copepod Mytilicola orientalis Mori. J. Insect Pathol., 4(4): 57-62. Theisen, B.F., 1987. Mytilicola intestinalis Steuer and the condition of its host Mytilus edulis L. Ophelia 27(2): 77-86. Tige, G., & Rabouin, M.A~, 1976. Etude d'un lot de moules transferees dans un centre touche par I'epizootie affectuant I'hiutre plate.I.C.E.S. C.M. 1976/K:21 Shellfish Committee. Yamauchi, K., 1984. The formation of Sargassum beds on artificial substrata by transplanting seedlings of S. horneri (Turner) c. Agardh and S. muticum (Yendo) Fensholt. Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries 50 (7): 1115-1123. ,, , Table 1. Importations of Pacific oyster, C. gigas, from France to Ireland during 1993 with associated organisms. * indicates oysters from a nursery system. + removed from the sea soon after introduction.' Oysters from the f first introduction to Carlingford had 2.7% to 5.3% infestation of M. orientalis on 10 March 1993, local ,'/, 't.: .~'.~. f ',I" :"~', ./ I' populations had none. ,.~ I, ,,,,: ,', ') ',1 1· \. \' Import date Area Relaycd Source 23-1-93 4-2-93 5-2-93 19-2-93 25·2·93 25-2-93 26-2-93 4-3-93 5-3-93 6-3-93 19-3-93 23-3-93 25-3-93 4-93 4-93 3/4-93 22-4-93 Carlingford Carlingford Dungarvan Dungarvan Dungarvan Cork Harb.+ Carlingford Dungarvan SampIe Dungarvan Carlingford Sampie * Dungarvan Sampie Oysterhaven Dunmanus Dungarvan Marennes Marennes Normandy Normandy Marennes Marennes Marennes Normandy Arcachon Normandy Marennes Normandy lrishIBritish Normandy Arcachon not knowll Normandy Quantity importcd Examincd 1717kg 4000kg 3300kg 3300kg 5340kg 770kg 9970kg 3300kg 4kg 3300kg 15000kg 2kg 2kg 2kg yes no no no yes yes ycs no yes no yes yes yes yes yes Number withM. ostrea present SampIe sizc Ostrea edulis Crepidula fornicata SampIe size %withM orientalist 113 0 1 86 7.3 308 5 1 0 67 23 82 14.9 4.3 9.7 ? 1721 0 0 80 3.7 3 138 46 68 230 60 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 30 46 68 60 40 0 30.3 0 0 0 0 0 0 6.6 5 I. , "\ >.; .. 1·I'i" 5 0 80 0 . :.,! 2 1 " J HO 3,000,000 " spat (0.5kg) ycs present ~i:j, ;' . I' . ~ . . , , .. IRELAND Y . Areas in which C. gigas fram France were reJaid. My ti licola 0 r i en ta lis . found in C.gigas fram Arcachan.Marenne/Oleronn , and St. Vaast Ja Hougue (Narmandy):