Comment on ‘‘The Illusion of Invariant Quantities in Life Histories’’

advertisement

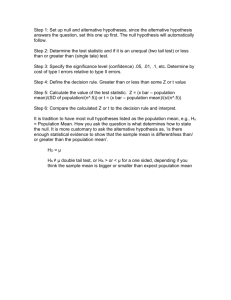

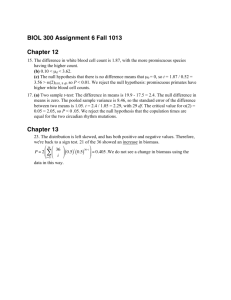

TECHNICAL COMMENT Comment on ‘‘The Illusion of Invariant Quantities in Life Histories’’ Van M. Savage,1* Ethan P. White,2,4 Melanie E. Moses,3 S. K. Morgan Ernest,2 Brian J. Enquist,4 Eric L. Charnov3 Nee et al. (Reports, 19 August 2005, p. 1236) used a null model to argue that life history invariants are illusions. We show that their results are largely inconsequential for life history theory because the authors confound two definitions of invariance, and rigorous analysis of their null model demonstrates that it does not match observed data. ecades of research on life history invariants have identified deep symmetries in evolutionary biology that reveal fundamental and pervasive constraints upon diverse organisms (1, 2). Nee et al. (3) constructed null models to argue that slopes and R2 from log-log plots cannot reliably identify invariants. This analysis has led others to conclude that life history invariants may not exist (4, 5). These conclusions are erroneous because they are based on a misrepresentation of life history invariants and on a failure to recognize that properties of these null models differ significantly from empirical data. Here, we show that Nee et al._s results are largely inconsequential for life history and allometric theories. Within life history theory, the term invariance is used in two ways. In type A invariance, a biological characteristic does not vary systematically with another characteristic, such as body size (6); in type B invariance, a biological characteristic exhibits a unimodal central tendency and varies over a limited range (7, 8). For example, the ratio of weaning mass to adult mass in mammals is a type A invariant because its value shows no trend with body size. In addition, this ratio is a type B invariant because weaning mass is typically close to 30% of adult mass. In his original work, Charnov (2) examines both types of invariants; however, he clearly emphasizes type A as the more important. He begins his book by stating that BSomething will be called invariant (or an invariant) if it does not change under the specified transformation[ and Bthe underlying transformation is adult body size between species.[ The null models of Nee et al., although presented and interpreted as posing problems for all life history invariants, are only relevant for de- D 1 Bauer Center for Genomics Research, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA. 2Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322, USA. 3Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA. 4Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA. *To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: vsavage@cgr.harvard.edu tecting type B invariance, as we now explain. If (i) the ratio of life history characteristics, c 0 y/x, is randomly distributed and (ii) VarEln(x)^ d VarEln(c)^, then it is straightforward to show analytically that the slope and R2 of ln( y) versus ln(x) are near 1. Nee et al._s null models satisfy these assumptions (3). By assuming condition (i), that y/x does not vary systematically with another variable, the simulated data of Nee et al. are type A invariants, by definition. Thus, they do not provide an alternative null model to this type of invariance. Indeed, the Nee et al. results demonstrate that slopes and R2 near 1 from log-log plots are valid for identifying type A invariance. Moreover, when c is drawn from a uniform random distribution with any reasonable choice of bounds (9), condition (ii) is satisfied, and therefore R2 , 1. Thus, Nee et al._s choice of the uniform random distribution, but not the specific bounds, is crucial for obtaining their results and, as such, the critical comparison to determine whether the observed data are described by this null is to compare the distribution of invariants to a uniform random distribution (10). When the null results of Nee et al. are rigorously compared with existing empirical data, Fig. 1. Plot of age at sexual maturity versus average adult life span for several taxa (13). The slope is the value of the life history ratio, and in all cases except the reptiles, the values differ significantly from those predicted by Nee et al.’s null (P G 0.01 in all cases; based on 10,000 draws of a mean value from the appropriate sample size). www.sciencemag.org SCIENCE VOL 312 it becomes obvious that the null fails to predict important biological properties of life history invariants and thus fails to describe type B invariance as well. First, the intercept from a regression on their null predicts a life history ratio, given by the distribution mean, that is independent of taxa. Therefore, Nee et al. cannot account for the observation that different clades or taxa are described by different values of c, representing important evolutionary differences between taxonomic groups (Fig. 1) (2). Second, many observed distributions of life history invariants are unimodal with a constrained range and thus significantly differ from Nee et al._s null model (Fig. 2). Third, their null model predicts R2 values that are in fact lower than those for real data (Fig. 2) (11, 12). Fourth, Nee et al._s testing of Fig. 2. Plots of observed data (in this case weaning mass/adult mass) and of Nee et al.’s null model based on the observed adult mass distribution. The observed data exhibit both types of invariants. Both real [77 values for mammals (13)] and simulated values of w/m are invariant with respect to size (P 9 0.1; lines are means), demonstrating that Nee et al.’s null assumes type A invariance. In addition to showing no trend with mass, histograms of invariants frequently differ significantly from Nee et al.’s uniform random distribution. For example, the distribution of w/m has a clear mode, contrary to the predictions of Nee et al.’s model (K-S test for deviation from uniform: P G 10j3). Evidence for this type of deviation is present in the literature in the form of plots of the distributions of invariants and linear plots of the relevant variables (2). In addition, their null predicts R2 values that, while high, are often significantly lower than those for real data (for this example, P G 10–5; based on 100,000 randomizations combining the observed adult mass distribution with 77 draws from a uniform distribution). 14 APRIL 2006 198b TECHNICAL COMMENT the ratio of annual clutch size to annual mortality rate against their null is clearly incorrect. Instead of using their null to calculate an expected R2, they use Ricklefs_ (13) empirical data to calculate the R 2 of the data, which is a statistical fact unrelated to their null model. Nee et al. incorrectly cite this as evidence against life history invariants. Using a uniform random distribution, corresponding to Nee et al._s null model, we find R2 0 0.44, much lower than that of Ricklefs_ empirical data (R2 0 0.84) and thus, evidence against Nee et al._s null. Further, contrary to claims by Nee et al. and others that life history theory implies that invariants show no variation, Charnov Ee.g., pp. 5 and 15 of (2)^ clearly states that a distribution is expected for any life history invariant. Indeed, life history theory endeavors to understand how natural selection sets both the central tendency and the distribution of these ratios (2, 7, 11). Finally, Nee et al._s null model can only produce slopes near 1 and, thus, contrary to concerns raised by de Jong and others (4, 5), cannot explain the ubiquitous quarter-power slopes observed in allometry or, by extension, the life history invariants formed from them (1, 2, 7). Life history invariants are governed by nonrandom processes and form the cornerstone of a general framework that mechanistically links variation in organismal form, function, ecology, and evolution across differing environments Ee.g., (1, 2, 8)^. For more than 40 years, fishery science has used them with great success Ee.g., (14)^. Life history invariants are certainly not illusions. 198b References and Notes 1. W. A. Calder, Size, Function, and Life History (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA, 1984). 2. E. L. Charnov, Life History Invariants: Some Explorations of Symmetry in Evolutionary Ecology (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1993). 3. S. Nee, N. Colgrave, S. A. West, A. Grafen, Science 309, 1236 (2005). 4. G. de Jong, Science 309, 1193 (2005). 5. Faculty of 1000 Biology: Evaluations for Nee S et al. Science 2005 Aug 19 309 (5738):1236-9; www.f1000biology.com/article/16109879/evaluation. 6. The fact that certain quantities are invariant with respect to a given variable or transformation is the traditional definition of invariant in math and statistics and also the one clearly given in regards to life history theory (2). This is because the vast majority of life history parameters depend on body mass [e.g., (1, 2)], so that invariants represent an important and meaningful exception to the rule (2). For example, the number of heartbeats in an organism’s lifetime does not change systematically as a function of body size. 7. This use of invariant (addressed by Nee et al.) is not well defined in the literature. Our reading of it is based on statements such as, ‘‘This [invariant] suggests that there is a fundamental similarity across all animals, from a 2-mm-long crustacean to a 1.5-m-long fish, in the underlying forces that select for sex change’’ [(8); see also (2)]. This implies a unimodal distribution, suggestive of an optimal value. That this value may be optimal is further revealed by examination of the corresponding allometric relationships. For example, primates have slow biomass production rates, which distinguishes them from other mammals when life history characteristics are plotted against mass [figures 1.13 and 6.4 in (2)]. However, primates are similar to other mammals when dimensionless comparisons are made (e.g., yearly clutch size multiplied by age at maturity is invariant [figure 1.3 in (2)] because biomass production rate cancels out in this ratio. 8. D. J. Allsop, S. A. West, Nature 425, 783 (2003). 9. If c is drawn from a uniform random distribution with a lower bound of 0, then Var[ln(c)] 0 1, condition (ii) is satisfied for most data, and R2 , 1, regardless of the upper bound for c. If the upper bound is less than a billion, then 14 APRIL 2006 VOL 312 SCIENCE 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Var[ln(c)] G 100, condition (ii) is satisfied for most data, and R2 , 1, regardless of the lower bound for c. Thus, although Nee et al.’s choice of uniform random distributions is crucial for obtaining their results, the specific choice of bounds (0 e c e1), which they and others emphasize as important (4, 5), is essentially irrelevant. This is crucial because otherwise their Eq. 4 would be invalid as E is clearly not bounded between 0 and 1. Contrary to Nee et al.’s suggestion that distributions other than the uniform random could be used for generating values for c, it is clear that the uniform random (constrained by logical bounds) is the only distribution justified as a true null based on the bounding of the data (12). Any other distribution would have the potential to smuggle biology into the null model. A. Gardner, D. J. Allsop, E. L. Charnov, S. A. West, Am. Nat. 165, 551 (2005). R. Cipriani, R. Collin, J. Evol. Biol. 18, 1613 (2005). Methods are available as supporting material on Science Online. R. J. H. Beverton, S. J. Holt, in Ciba Foundation Colloquia in Ageing. V. The Lifespan of Animals, G. E. W. Wolstenholme, M. O’Connor, Eds. (Churchill, London, 1959), pp. 142–177. We thank A. Allen, J. Brown, J. Gillooly, and G. West for helpful discussions during the development of this comment. V.M.S. acknowledges support from NIH through the Bauer Center for Genomics Research, E.P.W. acknowledges an NSF postdoctoral fellowship in Biological Informatics, and B.J.E. was supported by an NSF Faculty Early Career Development Program award and a Department of Energy Los Alamos National Laboratory grant. M.E.M. acknowledges support from the Department of Energy through a Los Alamos National Laboratory– University of New Mexico Collaborative Research grant. Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/312/5771/198b/DC1 Methods References 9 December 2005; accepted 15 March 2006 10.1126/science.1123679 www.sciencemag.org