T UTOR

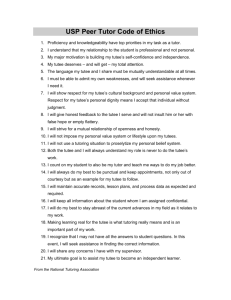

advertisement