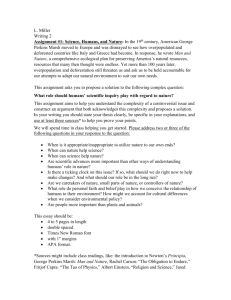

T D A F

advertisement