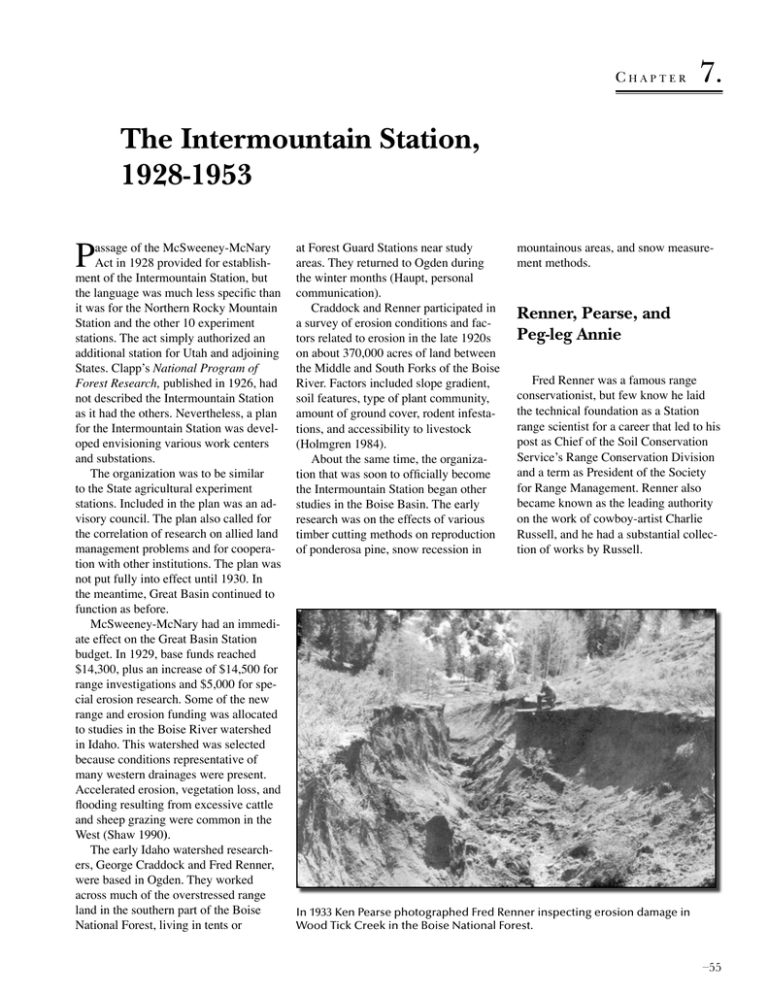

P 7. The Intermountain Station, C

advertisement