Interspecifi c and Intraspecifi c Picea engelmannii and its Congeneric Cohorts:

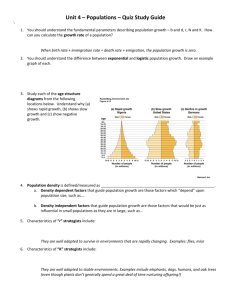

advertisement