Sectional Parties, Divided Business Cathie Jo Martin, Boston University

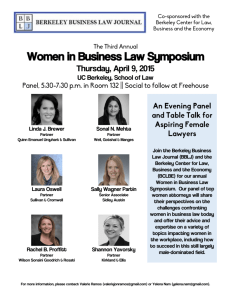

advertisement