48 of 61 DOCUMENTS Copyright (c) 1994 Southern California Law Review

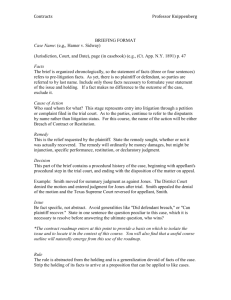

advertisement