Cincinnati Enquirer, OH 12-27-07 Scientific skeptics have a right to be heard

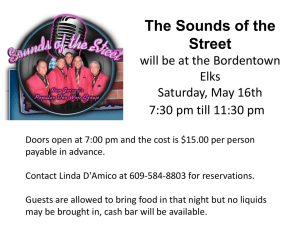

advertisement

Cincinnati Enquirer, OH 12-27-07 Scientific skeptics have a right to be heard BY CLYDE E. STAUFFER In the 16th century a large, powerful institution saw itself as threatened by heretics - people who didn't agree with all its dogmas - so it began to identify and punish those dissidents. Five hundred years later a similar effort is under way. In the 16th century it was the Roman Catholic church; today it is Big Science. The only real difference is that today heretics are simply deprived of their livelihood; burning at the stake is no longer in vogue. Exhibit One in this contention is found on Page A2 of the Dec. 14 Enquirer: "Global-warning skeptic says he's being vilified." This is from an economist, but scientists who express similar doubts about the fashionable view (global warming is due to generation of CO2 by humans) are similarly marginalized. Exhibit Two is the denial of tenure to Guillermo Gonzalez by the astronomy department of Iowa State University, despite a stellar record of scientific publications. His crime? He co-authored a book ("The Privileged Planet") that suggested that the unusually benign (for life) situation of the Earth might have been due to an intelligent designer. As a doctoral student I was taught that good science sought reliable facts about the world around us, and hypotheses followed wherever those facts lead. Sadly, that no longer seems to be the case. Instead, selected facts have led to politicized conclusions, and countervailing facts are no longer tolerated. This is not good science. The 16th century Inquisitors had, as part of their agenda, the salvation of the heretic's soul; the preservation of institutional power was a useful side result. Today's inquisitors no longer have even that touch of humanity; the preservation of their power as the ultimate arbiters of "truth" is their only goal. To end this Inquisition, scientists dedicated to good science must defend the right of skeptics to be heard. Clyde E. Stauffer of Finneytown earned a Ph.D. in biochemistry at the University of Minnesota, has done research at Procter & Gamble, and has been involved in more applied science for the last 30 years.