SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD ESTIMATORS FOR DISCRETELY OBSERVED JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

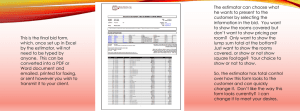

advertisement

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD ESTIMATORS FOR

DISCRETELY OBSERVED JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

By Kay Giesecke and Gustavo Schwenkler∗

Stanford University and Boston University

This paper develops an unbiased Monte Carlo approximation to

the transition density of a jump-diffusion process with state-dependent

drift, volatility, jump intensity, and jump magnitude. The approximation is used to construct a likelihood estimator of the parameters

of a jump-diffusion observed at fixed time intervals that need not be

short. The estimator is asymptotically unbiased for any sample size.

It has the same large-sample asymptotic properties as the true but

uncomputable likelihood estimator. Numerical results illustrate its

advantages.

1. Introduction. Continuous-time jump-diffusion processes are widely

used in a range of disciplines. This paper addresses the parameter inference

problem for a jump-diffusion observed at fixed time intervals that need not

be short. We develop an unbiased Monte Carlo approximation to the transition density of the process, and use it to construct likelihood estimators

of the parameters specifying the dynamics of the process. The results include asymptotic unbiasedness, consistency, and asymptotic normality as

the sample period grows. Our approach is motivated by (i) the fact that it

offers asymptotically unbiased and efficient estimation at any observation

frequency, and (ii) its computational advantages in calculating and maximizing the likelihood.

More specifically, we consider a one-dimensional jump-diffusion process

∗

Schwenkler is corresponding author. Schwenkler acknowledges support from a Mayfield

Fellowship and a Lieberman Fellowship. We are grateful to Rama Cont, Darrell Duffie,

Peter Glynn, Emmanuel Gobet, Marcel Rindisbacher, Olivier Scaillet, and the participants at the Bachelier World Congress, the BU Conference on Credit and Systemic Risk,

the Conference on Computing in Economics and Finance, the European Meeting of the

Econometric Society, the INFORMS Annual Meeting, the SIAM Financial Mathematics

and Engineering Conference, and seminars at Boston University, Carnegie Mellon University, the Federal Reserve Board, the University of California at Berkeley, and the Worcester

Polytechnic Institute for useful comments. We are also grateful to Francois Guay for excellent research assistance. An implementation in R of the methods developed in this paper

can be downloaded at http://people.bu.edu/gas.

Keywords and phrases: Density estimator, Parameter estimator, Maximum likelihood,

Exact simulation, Unbiased estimation, Jump-diffusions

1

2

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

whose drift, volatility, jump intensity, and jump magnitude are allowed to be

arbitrary parametric functions of the state. We develop unbiased simulation

estimators of the transition density of the process and its partial derivatives. Our approach can be extended to time-inhomogenous jump-diffusions

and certain multi-dimensional jump-diffusions. Volatility and measure transformation arguments are first used to represent the transition density as

a mixture of weighted Gaussian distributions, generalizing the results of

Dacunha-Castelle and Florens-Zmirou (1986) and Rogers (1985) for diffusions. A weight takes the form of a conditional probability that a certain

doubly-stochastic Poisson process has no jumps in a given interval. We develop an unbiased Monte Carlo approximation of that probability using an

exact sampling method, building on the schemes proposed by Beskos and

Roberts (2005), Chen and Huang (2013) and Giesecke and Smelov (2013)

for sampling the solutions of stochastic differential equations. The resulting

transition density estimator is unbiased and almost surely non-negative for

any argument of the density.1 Its accuracy depends only on the number of

Monte Carlo replications used, making it appropriate for any time interval.

Moreover, the estimator can be evaluated at any value of the parameter

and arguments of the density function without re-simulation. This property

generates computational efficiency for the simulated likelihood problem. It

reduces the maximization of the simulated likelihood to a deterministic problem that can be solved using standard methods.

We analyze the asymptotic behavior of the estimator maximizing the simulated likelihood for a fixed observation frequency.2 The estimator converges

almost surely to the true likelihood estimator as the number of Monte Carlo

replications grows, for a fixed sample period (an asymptotic unbiasedness

property). This ensures that the estimator inherits the consistency, asymptotic normality, and asymptotic efficiency of the true likelihood estimator if

the number of Monte Carlo replications grows at least as fast as the sample period. Our estimator does not suffer from the second-order bias generated by a conventional Monte Carlo approximation of the transition density,

which relies on a time-discretization of the process and non-parametric kernel estimation.3 Our exact Monte Carlo approach eliminates the need to

discretize the process and perform kernel estimation. It facilitates asymp1

Given that we do not require any debiasing technique, our non-negativity result does

not contradict the finding of Jacob and Thiery (2015).

2

Bibby and Sørensen (1995), Florens-Zmirou (1989), and Gobet, Hoffmann and Reiß

(2004) consider various diffusion estimators in a similar asymptotic regime.

3

Detemple, Garcia and Rindisbacher (2006) analyze this bias in the diffusion case and

propose a bias-corrected discretization scheme. For jump-diffusions with state-independent

coefficients, Kristensen and Shin (2012) provide conditions under which the bias is zero.

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

3

totically unbiased and efficient likelihood estimation.

Numerical results illustrate the accuracy and computational efficiency of

the density approximation as well as the performance of the simulated likelihood estimator. Our density estimator is found to outperform alternative

estimators of the transition density, both in terms of accuracy and computational efficiency. The error of our density estimator converges at the fastest

rate. Moreover, our density estimator entails the smallest computational cost

per observation when calculating the likelihood. The cost decreases as more

observations become available. Performing maximum likelihood estimation

for simulated monthly and quarterly data, we confirm that our simulated

likelihood estimator behaves indeed as the true maximum likelihood estimator, as predicted by our theoretical results. Our numerical results indicate

that the distribution of our simulated likelihood estimator for finite data

samples and a finite number of Monte Carlo replications is similar to that

of the true likelihood estimator. They also indicate that our estimator compares favorably to alternative simulation-based likelihood estimators when

a fixed computational budget is given.

Our results have several important applications. Andrieu, Doucet and

Holenstein (2010) show that an unbiased density estimator can be combined with a Markov Chain Monte Carlo method to perform exact Bayesian

estimation. Thus, our density estimator enables exact Bayesian estimation

of jump-diffusion models with general coefficients. Focusing on pure diffusion models, Semaidis et al. (2013) take a step in this direction. Based on

the results of these authors, we conjecture that the beneficial properties of

our estimators carry over to the Bayesian case.

The transition density estimator can also be used to perform efficient

generalized method of moments (GMM) estimation of jump-diffusions. It

is well-known that the optimal instrument that yields maximum likelihood

efficiency for GMM estimators is a function of the underlying transition

density (see Feuerverger and McDunnough (1981) and Singleton (2001)).

Our unbiased density estimator can be used instead of the unknown true

density. This enables efficient GMM estimation for many jump-diffusions

that were previously intractable.4

Finally, the transition density approximation generates an unbiased estimator of an expectation of a given function of a jump-diffusion evaluated

at a fixed horizon. In financial applications, for example, the expectation

might represent the value of a derivative security. Prices at different model

parameter values can be computed without having to re-simulate the tran4

Approximate GMM estimators that achieve efficiency have recently been proposed by

Carrasco et al. (2007), Chen, Peng and Yu (2013), and Jiang and Knight (2010).

4

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

sition density, generating computational efficiency in econometric applications. Traditional discretization-based approaches to estimating the transition density (see, e.g., Platen and Bruti-Liberati (2010)) generate biased

estimators of security prices. Exact sampling approaches to estimating the

density (e.g., Giesecke and Smelov (2013)) generate unbiased estimators of

prices but might be computationally burdensome.

We have implemented the transition density approximation and the likelihood estimator in R. The code can be downloaded at http://people.bu.

edu/gas. It can be easily customized to treat a given jump-diffusion.

1.1. Related literature. Prior research on the parametric inference problem for discretely-observed stochastic processes has focused mostly on diffusions. Of particular relevance to our work is the Monte Carlo likelihood

estimator for diffusions proposed by Beskos, Papaspiliopoulos and Roberts

(2009). They use the exact sampling method of Beskos, Papaspiliopoulos

and Roberts (2006) to approximate the likelihood for a discretely-observed

diffusion. In the absence of jumps, our estimator reduces to their estimator.

However, our approach requires weaker assumptions, so our estimator has a

broader scope even in the diffusion case. Moreover, our approach allows us

to optimize the computational efficiency of estimation.

Lo (1988) treats a jump-diffusion with state-independent Poisson jumps

by numerically solving the partial integro differential equation governing

the transition density. Kristensen and Shin (2012) analyze a nonparametric

kernel estimator of the transition density of a jump-diffusion with stateindependent coefficients.5 Aı̈t-Sahalia and Yu (2006) develop saddlepoint

expansions of the transition densities of Markov processes, focusing on jumpdiffusions with state-independent Poisson jumps and Lévy processes. Filipović, Mayerhofer and Schneider (2013) analyze polynomial expansions of

the transition density of an affine jump-diffusion. Li (2013) studies a power

series expansion of the transition density of a jump-diffusion with stateindependent Poisson jumps. Yu (2007) provides a small-time expansion of

the transition density of a jump-diffusion in a high-frequency observation

regime, assuming a state-independent jump size. The associated estimator inherits the asymptotic efficiency of the theoretical likelihood estimator as the observation frequency grows large; see Chang and Chen (2011)

for the diffusion case. Jiang and Knight (2002), Chacko and Viceira (2003),

Duffie and Glynn (2004), and Duffie and Singleton (1993) develop gener5

The assumption that the distribution of t is independent of t and θ in equation

(1) of Kristensen and Shin (2012) effectively restricts their model to state-independent

jump-diffusions.

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

5

alized method of moments estimators for jump-diffusions and other timehomogenous Markov processes. If an infinite number of moments is used,

then these estimators inherit the asymptotic properties of the theoretical

likelihood estimator. This, however, is infeasible in practice.

Unlike the transition density approximations developed in the aforementioned papers, our unbiased Monte Carlo approximation of the transition

density applies to jump-diffusions with general state-dependent drift, diffusion, jump intensity, and jump size. Beyond mild regularity, no structure is

imposed on the coefficient functions. The approximation has a significantly

wider scope than existing estimators, including, in particular, models with

state-dependent jumps and non-affine formulations. The simulated likelihood estimator inherits the asymptotic efficiency of the theoretical likelihood estimator as both the sample period and the number of Monte Carlo

replications grow, for any observation frequency.

1.2. Structure of this paper. Section 2 formulates the inference problem.

Section 3 develops a representation of the transition density of a jumpdiffusion. Section 4 uses this representation to construct an unbiased Monte

Carlo estimator of the density and its partial derivatives. Section 5 discusses the implementation of the estimator. Section 6 analyzes the asymptotic behavior of the estimator maximizing the simulated likelihood. Section

7 presents numerical results. There are two technical appendices, one containing the proofs.

2. Inference problem. Fix a complete probability space (Ω, F, P) and

a right-continuous, complete information filtration (Ft )t≥0 . Let X be a

Markov jump-diffusion process valued in S ⊂ R that is governed by the

stochastic differential equation

(1)

dXt = µ(Xt ; θ)dt + σ(Xt ; θ)dBt + dJt ,

where X0 is a constant, µ : S × Θ → R is the drift function, σ : S ×

Θ →P

R+ is the volatility function, B is a standard Brownian motion, and

t

Jt = N

n=1 Γ(XTn − , Dn ; θ) for a N is a non-explosive counting process with

event stopping times (Tn )n≥1 and intensity λt = Λ(Xt ; θ) for a function Λ :

S × Θ → R+ . The function Γ : S × D × Θ → R governs the jump magnitudes

of X, and (Dn )n≥1 is a sequence of i.i.d. mark variables with probability

density function π on D ⊂ R. The drift, volatility, jump intensity, and jump

size functions are specified by a parameter θ ∈ Θ to be estimated, where the

parameter space Θ is a subset of Euclidean space. More specifically, X is a

Markov process with infinitesimal generator for functions f with bounded

6

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

and continuous first and second derivatives given by

Z

1

0

00

(f (x + Γ(x, u; θ)) − f (x)) π(u)du.

µ(x; θ)f (x) + σ(x; θ)f (x) + Λ(x; θ)

2

D

We impose the following assumptions. First, the boundary of S is unattainable. Second, the parameter space Θ is a compact subset of Rr with nonempty interior for r ∈ N. Third, the SDE (1) admits a unique strong solution.

Sufficient conditions are given in (Protter, 2004, Theorem V.3.7). Finally,

X admits a transition density. Cass (2009) provides sufficient conditions.

Our goal is to estimate the parameter θ specifying the dynamics of X

given a sequence of values X = {Xt0 , . . . , Xtm } of X observed at fixed times

0 = t0 < · · · < tm < ∞. For ease of exposition, we assume that ti −

ti−1 = ∆ for all i and some fixed ∆ > 0. The data X is a random variable

valued in S m and measurable with respect to B m , where B is the Borel

σ-algebra on S. The likelihood of the data is the Radon-Nikodym density

of the law of X with respect to the Lebesgue measure on (S m , B m ). Let

pt (x, ·; θ) be the Radon-Nikodym density of the law of Xt given X0 = x

with respect to the Lebesgue measure on (S, B), i.e., the transition density

of X. Given the Q

Markov property of X, the likelihood function L(θ) takes

the form L(θ) = m

i=1 p∆ (X(i−1)∆ , Xi∆ ; θ). A maximum likelihood estimator

(MLE) θ̂m satisfies θ̂m ∈ arg maxθ∈Θ L(θ) almost surely. We only consider

interior MLEs for which ∇L(θ)|θ=θ̂m = 0 Throughout, let ∇ and ∇2 denote

the gradient and the Hessian matrix operators, respectively. Also, assume

that θ = (θ1 , . . . , θr ). For any 1 ≤ i1 , . . . , in ≤ r, write ∂in1 ,...,in for the n-th

partial derivative with respect to θi1 , . . . , θin .

Suppose the true data-generating parameter θ∗ ∈ int Θ. Appendix A provides sufficient conditions for consistency and asymptotic normality of a

MLE θ̂m as m → ∞. Unlike the well-known standard hypotheses (see, e.g.,

(Singleton, 2006, Chapter 3)), our conditions do not require knowledge of the

true data-generating parameter. Our conditions can be verified in practice

using an unbiased Monte Carlo approximation to p∆ developed in Section

3. On the other hand, they are somewhat stronger than the standard hypotheses because they need to hold globally in the parameter space.

Some assumptions were made for clarity in the exposition and can be

relaxed. We can extend to time-inhomogenous Markov jump-diffusions, for

which the coefficient functions may depend on state and time. It is straightforward to treat the case of observation interval lengths ti − ti−1 that vary

across i, the case of a random initial value X0 , and the case of mark variables with parameter dependent density function π = π(·; θ). The analysis

can be extended to certain multi-dimensional jump-diffusions, namely those

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

7

that are reducible in the sense of Definition 1 in Aı̈t-Sahalia (2008). Finally,

we can also extend to settings in which the boundary ∂S is attainable. The

results presented below hold until the first hitting time of ∂S.

3. Transition density. Using volatility and measure transformation

arguments, this section develops a weighted Gaussian mixture representation

of the transition density p∆ of X.

3.1. Change of variables. We begin by applying a change of variables to

transform X

R winto1 a unit-volatility process. Define the Lamperti transform

F (w; θ) = X0 σ(u;θ) du for w ∈ S and θ ∈ Θ. For every θ ∈ Θ, the mapping w 7→ F (w; θ) is well-defined given that σ(u; θ) > 0 for all u ∈ S. Set

Yt = F (Xt ; θ) on the state space SY = F (S; θ). If σ(x; θ) is continuously

differentiable in x, then Itô’s formula implies that Y solves the SDE

dYt = µY (Yt ; θ)dt + dBt + dJtY ,

Y0 = F (X0 ; θ) = 0,

up to the exit time of SY . Since 0 < σ(u; θ) < ∞ for all u ∈ S, θ ∈ Θ, it

follows that F is invertible with respect to w ∈ S. Let F −1 (y; θ) denote the

inverse of F , such that F (F −1 (y; θ); θ) = y. The drift function of Y satisfies

µY (y; θ) =

µ(F −1 (y; θ); θ) 1 0 −1

− σ (F (y; θ); θ)

σ(F −1 (y; θ); θ) 2

in the interior of SY . The Lamperti transform does not affect the jump intensity of N , but it alters the jump magnitudes of the P

state process. The process

t

Y

Y

J describing the jumps of Y is given by Jt = N

n=1 ΓY (YTn − , Dn ; θ) for

the jump size function

ΓY (y, d; θ) = F F −1 (y; θ) + Γ(F −1 (y; θ), d; θ); θ − y,

y ∈ SY .

The Lamperti transformation can be understood as a change of variables.

If X has a transition density p∆ , then Y has a transition density, denoted

pY∆ . We have pY∆ (F (v; θ), F (w; θ); θ) = p∆ (v, w; θ)σ(w; θ).

3.2. Change of measure. To facilitate the computation of the transition

density pY∆ , we change from Pθ to a measure Qθ under which Y has constant

drift ρ ∈ R and the jump counting process N is a Poisson process with some

D (θ)Z P (θ), where

fixed rate ` > 0. Define the variable Z∆ (θ) = Z∆

∆

Z ∆

Z ∆

1

2

D

(2) Z∆ (θ) = exp −

(µY (Ys ; θ) − ρ) ds −

(µY (Ys ; θ) − ρ) dBs

2 0

0

Z ∆

Y

N∆

`

P

(θ) = exp

Λ(F −1 (Ys ; θ); θ) − ` ds

(3) Z∆

−1 (Y

Λ(F

Tn − ; θ); θ)

0

n=1

8

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

for θ ∈ Θ. If Eθ [Z∆ (θ)] = 1, we can define an equivalent probability measure

Qθ on (Ω, F∆ ) by Qθ [A] = Eθ [Z∆ (θ)1A ] for any A ∈ F∆ . If µY (y; θ) is

continuously differentiable in y, integration by parts implies that

Z

(4) Z∆ (θ) = exp a(Y0 ; θ) − a(Y∆ ; θ) +

∆

b(Ys ; θ)ds

0

Y

N∆

n=1

1

c(YTn − , Dn ; θ)

where a, b : SY × Θ → R and c : SY × D × Θ → R are given by

Z y

(µY (u; θ) − ρ) du,

a(y; θ) =

0

µ2Y (y; θ) − ρ2 + µ0Y (y; θ)

,

2

!

Z y+ΓY (y,d;θ)

Λ(F −1 (y; θ); θ)

(µY (u; θ) − ρ) du .

exp −

c(y, d; θ) =

`

y

b(y; θ) = Λ(F −1 (y; θ); θ) − ` +

The theorems of Girsanov,

Lévy, and Watanabe imply that, under Qθ and

Rt

on [0, ∆], Wt = Bt + 0 (µY (Ys ; θ) − ρ)ds is a standard Qθ -Brownian motion,

N is a Poisson process with rate `, the random variables (Dn )n≥1 are i.i.d.

with density π, and Y is governed by the stochastic differential equation

dYt = ρdt + dWt + dJtY .

(5)

Under Qθ , the process Y is a jump-diffusion with state-independent Poisson

jumps that arrive at rate `. The size of the nth jump of Y is a function of

YTn − and Dn , where the Dn ’s are i.i.d. variables with density π. Between

jumps, Y follows a Brownian motion with drift ρ. Thus, Y is a strong Markov

process under Qθ .

3.3. Density representation. We exploit the volatility and measure transformations to represent the transition density p∆ as a mixture of weighted

Gaussian distributions.

Theorem 3.1.

Fix ∆ > 0. Suppose the following assumptions hold.

(B1) For any θ ∈ Θ, the function u 7→ µ(u; θ) is continuously differentiable

and the function u 7→ σ(u; θ) is twice continuously differentiable.

(B2) For any θ ∈ Θ, the expectation Eθ [Z∆ (θ)] = 1.

Let v, w be arbitrary points in S and x, y be arbitrary points in SY . Let Y x

be the solution of the SDE (5) on [0, ∆] with Y0 = x. Then

(6)

p∆ (v, w; θ) =

ea(F (w;θ);θ)−a(F (v;θ);θ)

Ψ∆ (F (v; θ), F (w; θ); θ)

σ(w; θ)

9

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

for any θ ∈ Θ, where

"

Ψ∆ (x, y; θ) =

EQ

θ

Z

exp −

0

∆

Y

N∆

b(Ysx ; θ)ds

c(YTxn − , Dn ; θ)

n=1

(7)

1

×p

exp

2π(∆ − TN∆ )

−

y − ρ (∆ − TN∆ ) − YTxN

2 !#

∆

.

2 (∆ − TN∆ )

Assumption (B1) is standard. Assumption (B2) guarantees that the change

of measure is well-defined. Sufficient conditions for Assumption (B2) are

given by Blanchet and Ruf (2013), for example.

The representation (6) can be thought of as arising from Bayes’ formula

as the product of the conditional Qθ -law of Y∆x given (Tn , YTxn )n≤N∆ and the

Qθ -law of (Tn , YTxn )n≤N∆ . The former is represented by the density function

1

p

exp

2π(∆ − TN∆ )

−

y − ρ(∆ − TN∆ ) − YTxN

2 (∆ − TN∆ )

2 !

∆

,

which is Gaussian because Y x follows a Brownian motion with drift between

jumps and ∆ is fixed. The expectation (7) integrates this density according

to the Qθ -law of (Tn , YTxn )n≤N∆ . The additional terms appearing in (6) take

account of the changes of variable and measure.

Theorem 3.1 also applies in the diffusion case (Γ ≡ 0). In this case, (6)

provides a significant generalization of the diffusion density representations

of Dacunha-Castelle and Florens-Zmirou (1986) and Rogers (1985). Compared to these, we extend the state space by introducing the counting process

N , which allows us to employ the change of measure defined by the RadonNikodym densities (2)-(3) and parametrized by the Poisson rate ` and the

drift ρ. As explained in Section 5, the ability to select ρ and ` facilitates the

construction of computationally efficient density estimators.

We exploit the representation (6) to develop conditions under which the

transition density is smooth with respect to the parameter θ. Smoothness is

often required for consistency and asymptotic normality of a MLE θ̂m ; see,

e.g., Appendix A.

Proposition 3.2. Suppose that the conditions of Theorem 3.1 hold. Furthermore, suppose that the following conditions also hold.

(B3) The functions (u, θ) 7→ Λ(u; θ) and (u, d, θ) 7→ Γ(u, d; θ) are n-times

continuously differentiable in (u, d, θ) ∈ S × D × Θ. The function

10

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

(u, θ) 7→ µ(u; θ) is (n + 1)-times continuously differentiable. The function (u, θ) 7→ σ(u; θ) is (n + 2)-times continuously differentiable in

(u, θ) ∈ S × Θ.

(B4) The order of differentiation and Qθ -expectation can be interchanged

for Ψ∆ (x, y; θ) for the n-th partial derivative taken with respect x, y,

or θ. In other words, for qi1 , . . . , qin ∈ {θ1 , . . . , θr , x, y},

∂n

∂n

Q

Ψ∆ (x, y; θ) = Eθ

H(x, y; θ)

∂qi1 . . . ∂qin

∂qi1 . . . ∂qin

where H(x, y; θ) is the integrand of Ψ∆ in (7).

Then θ 7→ p∆ (v, w; θ) is n-times continuously differentiable for any v, w ∈ S.

Condition (B4) is intentionally formulated loosely as there are many sufficient conditions that allow for the interchange of expectation and differentiation. For example, invoking the bounded convergence theorem, a sufficient condition is that the difference quotients of n-th order of H(x, y; θ)

are uniformly bounded. A necessary condition according to Section 7.2.2 of

Glasserman (2003) is that the difference quotients are uniformly integrable.

4. Transition density estimator. This section develops an unbiased

Monte Carlo estimator of the transition density p∆ based on the representation obtained in Theorem 3.1. The key step consists of estimating the

expectation (7). For values w1 , w2 ∈ R, time t > 0, parameter θ ∈ Θ, and a

standard Qθ -Brownian motion W , define the function f (v, w, t; θ) as

Z t

Q

(8)

Eθ exp −

b(v + ρu + Wu ; θ)du Wt = w − v − ρt .

0

By iterated expectations, the strong Markov property, and the fact that Y x

follows a Brownian motion with drift between jumps under Qθ , we have

2

y−ρ(∆−TN )−YTx

"

∆

N∆

x

x

f (YTN , Y∆ , ∆ − TN∆ ; θ) −

2(∆−TN )

∆

p∆

Ψ∆ (x, y; θ) = EQ

e

θ

2π(∆

−

T

)

N

∆

(9)

#

N∆

Y

×

c(YTxn − , Dn ; θ)f (YTxn−1 , YTxn − , Tn − Tn−1 ; θ) .

n=1

In order to construct an unbiased Monte Carlo estimator of (9), we require

exact samples of several random quantities. Samples of N∆ and the jump

times (Tn )n≤N∆ of the Qθ -Poisson process N can be generated exactly (using

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

11

the order statistics property, for example). Under Qθ , the variables Y∆x and

YTxn − are conditionally Gaussian so samples can also be generated exactly.

Moreover, the marks (Dn )n≤N∆ can be sampled exactly from the Qθ -density

π by the inverse transform method, for example. The only non-trivial task

is the unbiased estimation of the expectation (8). We extend an approach

developed by Beskos and Roberts (2005) for the exact sampling of a diffusion.

To see how an unbiased estimator can be constructed, suppose the function b is positive. Then (8) is the conditional probability that a doublystochastic Poisson process with intensity b(v + ρs + Ws ; θ) has no jumps in

the interval [0, t], given (W0 , Wt ). If b is also bounded, then this probability

can be estimated without bias using a simple thinning scheme (Lewis and

Shedler (1979)). Here, one generates the jump times τ1 < · · · < τp of a dominating Poisson process on [0, t] with intensity maxw b(w; θ), and a skeleton

Wτ1 , . . . , Wτp of a Brownian bridge starting from 0 at time 0 and ending at

w − v − ρt at time t. An estimator of the desired no-jump probability is

p Y

b(v + ρτi + Wτi ; θ)

(10)

1−

,

maxw b(w; θ)

i=1

which is the empirical probability of rejecting the jump times of the dominating Poisson process as jump times of a doubly-stochastic Poisson process

with intensity b(v + ρs + Ws ; θ) conditional on Wt = w − v − ρt.

This approach extends to the case where b is not necessarily bounded or

positive; see Chen and Huang (2013) for the case ρ = 0. We partition the

interval [0, t] into segments in which W is bounded. Let η = min{t > 0 :

Wt ∈

/ [−L, L]} for some level L > 0 whose choice will be discussed below. If

the function b is continuous, then

(11)

b(v + ρt + Wt ; θ) −

min

|w|≤L+|ρ|η

b(v + w; θ)

is positive and bounded for t ∈ [0, η]. Consequently, we can use the estimator

(10) locally up to time η if we replace the function b with (11). We iterate

this localization argument to obtain an unbiased estimator of (8). Let (ηi :

i = 1, . . . , I + 1) be i.i.d. samples of η for I = sup{i : η1 + · · · + ηi ≤ t} and

set E0 = 0, Ei = η1 + · · · + ηi . In addition, let τ1i < · · · < τpii be a sample of

the jump times of a dominating Poisson process on [0, ηi ] with rate Mi (θ)

given by

max

b v + ρEi−1 + WEi−1 + x; θ − b v + ρEi−1 + WEi−1 + y; θ .

|x|,|y|≤L+|ρ|ηi

Note that 0 ≤ Mi (θ) < ∞ for all y ∈ SY if b is continuous. Finally, define

τ0i = 0, wi,0 = WEi−1 , and let wi,1 , . . . , wi,pi be a skeleton of the Brownian

12

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

bridge starting at WEi−1 at time Ei−1 and finishing at WEi at time Ei .

Letting mi (θ) = min|w|≤L+|ρ|ηi b(v + ρEi−1 + WEi−1 + w; θ), an unbiased

estimator of (8) is given by fˆ(v, w, t; θ) defined as

!

pi

I+1

i ) + w ; θ) − m (θ)

Y

Y

b(v

+

ρ(E

+

τ

i−1

i,j

i

j

(12)

e−mi (θ)Ei

1−

Mi (θ)

i=1

j=1

P

where EI+1 = t − Ii=1 Ei . This estimator generates an unbiased estimator

of the transition density of X.

Theorem 4.1. Fix the localization level L > 0, the Poisson rate ` > 0,

and the drift ρ ∈ R. Set

2

y−ρ(∆−TN )−YTx

∆

N∆

fˆ(YTxN , Y∆x , ∆ − TN∆ ; θ) a(y;θ)−a(x;θ)−

2(∆−TN )

∆

p̂∆ (v, w; θ) = p ∆

e

2π(∆ − TN∆ )σ(w; θ)

(13)

×

N∆

Y

c(YTxn − , Dn ; θ) fˆ(YTxn−1 , YTxn − , Tn − Tn−1 ; θ)

n=1

for x = F (v; θ) and y = F (w; θ). Suppose the following conditions hold:

(B5) For any θ ∈ Θ, v 7→ Λ(v; θ) is continuous, v 7→ µ(v; θ) is continuously

differentiable, and v 7→ σ(v; θ) is twice continuously differentiable.

(B6) At least one of the functions Λ, µ, σ, σ 0 , or σ 00 is not constant.

Then p̂∆ (v, w; θ) is an unbiased estimator of the transition density p∆ (v, w; θ)

for any v, w ∈ S, and θ ∈ Θ. That is, EQ

θ [p̂∆ (v, w; θ)] = p∆ (v, w; θ).

A simulation estimator of the transition density p∆ (v, w; θ) of the jumpdiffusion X is given by the average of independent Monte Carlo samples of

p̂∆ (v, w; θ) drawn from Qθ . Theorem 4.1 provides mild conditions on the

coefficient functions of X guaranteeing the unbiasedness of this estimator.

The practical implementation of the estimator will be discussed in Section

5, including the selection of the quantities L, ` and ρ.

The density estimator (13) also applies to a diffusion, i.e., in the absence

of jumps (Γ ≡ 0). In this case, and if Λ ≡ 0, ρ = 0, ` = 0, L = ∞,

and inf w∈SY b(w; θ) > ∞ and supw∈SY b(w; θ) − inf w∈SY b(w; θ) < ∞ for

all θ ∈ Θ, our density estimator reduces to the estimator of Beskos, Papaspiliopoulos and Roberts (2009). Our approach requires weaker assumptions, so our estimator has a broader scope even in the diffusion case. Moreover, our approach allows us to select the Poisson rate `, the drift ρ, and the

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

13

localization bound L, and this facilitates the construction of computationally

efficient density estimators (see Section 5).

Often, one is interested in evaluating partial derivatives of p∆ (v, w; θ). For

example, many sufficient conditions for consistency and asymptotic normality of a MLE θ̂m are formulated in terms of partial derivatives of the density;

see Appendix A. Conveniently, under certain conditions, the density estimator (13) can be differentiated to obtain unbiased estimators of the partial

derivatives of the transition density.

Corollary 4.2. Suppose that the conditions of Proposition 3.2 and

Theorem 4.1 hold. In addition, suppose that:

(B7) For any ξ > 0, the following functions are n-times continuously differentiable: (y, θ) 7→ minw∈[−ξ,ξ] b(y +w; θ) and (y, θ) 7→ maxw∈[−ξ,ξ] b(y +

w; θ).

(B8) The order of differentiation and Qθ -expectation can be interchanged

for p̂∆ (v, w; θ) for the n-th partial derivative taken with respect to θ;

i.e., for i1 , . . . , in ∈ {1, . . . , r},

Q n

∂in1 ,...,in EQ

θ [p̂∆ (v, w; θ)] = Eθ ∂i1 ,...,in p̂∆ (v, w; θ) .

Then the mapping θ 7→ p̂∆ (v, w; θ) is almost surely n-times continuously

differentiable for any v, w ∈ S. In addition, any n-th partial derivative of

p̂∆ (v, w; θ) with respect to θ is an unbiased estimator of the corresponding

partial derivative of p∆ (v, w; θ). That is, for i1 , . . . , in ∈ {1, . . . , r},

n

∂

p̂

(v,

w;

θ)

= ∂in1 ,...,in p∆ (v, w; θ).

EQ

∆

i

,...,i

θ

n

1

The assumptions of Proposition 3.2 together with Assumption (B7) imply

that the function fˆ in (12) is n-times continuously differentiable with respect

to all its arguments. This is a necessary condition for the differentiability

of the density estimator p̂∆ . Assumption (B8), again formulated loosely,

ensures the unbiasedness of a derivative estimator.

5. Implementation of density estimator. This section explains the

practical implementation of the transition density estimator (13). The algorithms stated below have been implemented in R and are available for

download at http://people.bu.edu/gas.

Fix L, ` > 0 and ρ ∈ R. To generate a sample of p̂∆ (v, w; θ), we require a

vector R = (P, T, E, W, V, D) of variates with the following properties:

• P ∼ Poisson(`∆) is a sample of the jump count N∆ under Qθ

• T = (Tn )1≤n≤P is a sample of the jump times (Tn )1≤n≤N∆ under Qθ

14

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

•

•

•

•

E = (Enk )1≤n≤P+1,k≥1 is a collection of i.i.d. samples of the exit time η

W = (Win )1≤n≤P+1,i≥1 is a collection of i.i.d. uniforms on {−L, L}

n )

V = (Vi,j

1≤n≤P+1,i,j≥1 is a collection of i.i.d. standard uniforms

D = (Dn )1≤n≤P is a collection of i.i.d. samples from the density π

The variates P and D can be sampled exactly using the inverse transform

method. The Poisson jump times T can be generated exactly as the order

statistics of P uniforms on [0, ∆]. The collection E of exit times can be

generated exactly using an acceptance-rejection scheme; see Section 4.1 of

Chen and Huang (2013). This scheme uses gamma variates. The sampling

of the remaining variates is trivial.

Algorithm 5.1 (Computation of Density Estimator).

S, θ ∈ Θ, do:

For given v, w ∈

(i) Set Y0x = x = F (v; θ) and y = F (w; θ).

(ii) For n = 1, . . . , P, do:

(a) Draw samples of YTxn − and YTxn under Qθ according to (5). Compute the quantity fˆ(YTxn−1 , YTxn − , Tn − Tn−1 ; θ) according to (12).

(iii) Draw samples of YTxP and Y∆x under Qθ and compute fˆ(YTxP , Y∆x , ∆ −

TP ; θ).

(iv) Compute the density estimator p̂∆ (v, w; θ) as

fˆ(YTxP , Y∆x , ∆ − TP ; θ) a(F (w;θ);θ)−a(F (v;θ);θ)−

p

e

2π(∆ − TP )σ(w; θ)

×

P

Y

2

y−ρ(∆−TP )−YTx

P

2(∆−TP )

c(YTxn − , Dn ; θ) fˆ(YTxn−1 , YTxn − , Tn − Tn−1 ; θ).

n=1

Only Steps (ii)a and (iii) of Algorithm 5.1 are nontrivial. The following

algorithm details the implementation of these steps.

Algorithm 5.2 (Sampling YTxn − and YTxn and computing fˆ(YTxn−1 , YTxn − ,

Tn − Tn−1 ; θ) ). Fix YTxn−1 , Tn−1 , Tn , and Dn . Let I = max{i ≥ 1 : E1 +

· · ·+Ei ≤ Tn −Tn−1 } and set w1,0 = YTxn−1 and wi,0 = wi−1,0 +ρEi−1 +Wi−1

for i = 2, . . . , I + 1. For i = 1, . . . , I + 1, do:

(i) Compute

mi =

Mi =

min

b(wi,0 + w; θ)

max

b (wi,0 + w; θ) − mi

|w|≤L+|ρ|Ei

|w|≤L+|ρ|Ei

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

15

(ii) Draw samples of the jump times τi,1 , . . . , τi,pi of a dominating Poisson

process with rate Mi . Set τi,0 = 0 and τi,j = τi,j−1 − (log Vi,j )/Mi for

j ≥ 1 while τi,j ≤ Ei . Set

pi =

max{j ≥ 0 : τi,j ≤ Ei },

P

max{j ≥ 0 : τi,j ≤ Tn − Tn−1 − Ii=1 Ei },

i = 1, . . . , I

i=I +1

(iii) Compute a skeleton wi,1 , . . . , wi,pi of a Brownian bridge reaching from

0 at time 0 to Wi at time Ei . For i = IP+ 1, compute the additional

skeleton point w− at time Tn − Tn−1 − Ii=1 Ei

(iv) Compute the normalizing factor

(

exp(−m

i = 1, . . . , I

i Ei ),

PI

ei =

i=I +1

exp −mi (Tn − Tn−1 − i=1 Ei ) ,

P

A sample of YTxn − is given by y − = wI+1,0 + w− + ρ(Tn − Tn−1 − Ii=1 Ei ).

A sample of YTxn is given by y + = y − + ΓY (y − , Dn ; θ). A sample of fˆ(YTxn−1 ,

YTxn − , Tn − Tn−1 ; θ) is given by

I+1

Y

i=1

ei

pi

Y

j=1

!

b wi,0 + wi,j + ρτi,pj ; θ − mi

1−

.

Mi

The correctness of Algorithm 5.2 follows from Theorem 4.1 after noting

that an exact sample of the first jump time of a Poisson process with rate

Mi (θ) is given by − log(U )/Mi (θ), where U is standard uniform. This observation is used in Step (ii). The skeleton of a Brownian bridge required in

Step (iii) can be sampled exactly using the procedure outlined in Section 6.4

of Beskos, Papaspiliopoulos and Roberts (2009), which constructs a skeleton

in terms of three independent sequences of standard normals.

Note that the vector of basic random variates R used in the algorithms

above does not depend on the arguments (v, w; θ) of the density estimator

(13). Thus, a single sample of R suffices to generate samples of p̂∆ (v, w; θ)

for any v, w ∈ S and θ ∈ Θ. This property generates significant computational benefits for the maximization of the simulated likelihood based on the

estimator (13); see Section 6.

We discuss the optimal selection of the level L, the Poisson rate `, and the

drift ρ. While these parameters have no impact on the unbiasedness of the

density estimator, they influence the variance and computational efficiency

of the estimator. The Poisson rate ` governs the frequency of the jumps of

X under Qθ . If ` is small, then TN∆ ≈ 0 with high Qθ -probability and the

16

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

estimator (13) approximates the density p∆ as a weighted Gaussian density,

ignoring the jumps of X. Thus, the estimator (13) has large variance in the

tails. On the other hand, the computational effort required to evaluate the

estimator increases with `. This is because EQ

θ [P] = `∆ so that Step (ii)a of

Algorithm 5.1 is repeated more frequently for large values of `.

The level parameter L controls the number of iterations I +1 in Algorithm

5.2. Note that Qθ [|Ytx | > L] → 0 as L → ∞ for any fixed 0 ≤ t ≤ ∆ because

Y x is non-explosive under Qθ . Thus, the larger L, the smaller I, and the

fewer iterations of Algorithm 5.2 are needed to compute (12). On the other

hand, large values of L make Mi (θ) large, which increases pi in (12) for

all 1 ≤ i ≤ I + 1. This, in turn, increases both the variance of the thinning

estimator (12) and the computational effort required to evaluate it. Similarly,

large positive or negative values of ρ also make Mi (θ) large, increasing both

the variance of the density estimator and the computational effort necessary

to evaluate it.

We propose to choose the quantities `, L, and ρ so as to optimally trade

off computational effort and variance. We adopt the efficiency concept of

Glynn and Whitt (1992) for simulation estimators, defining efficiency as the

inverse of the product of the variance of the estimator and the work required

to evaluate the estimator. Thus, we select `, L, and ρ as the solution of the

optimization problem

2

(14)

min

max EQ

θ p̂∆ (v, w; θ) × R(v, w; θ),

`,L>0,ρ∈R v,w∈S

θ∈Θ

where R(v, w; θ) is the time required to compute the estimator for given v,

w, θ, `, L, and ρ. The solution of this optimization problem leads to a density

estimator that is efficient across the state and the parameter spaces.6

The problem (14) is a non-linear optimization problem with constraints,

which can be solved numerically using standard methods. A run of Algorithm

5.1 yields R(v, w; θ) for given v, w, θ, `, L, and ρ. An unbiased estimator

2

of the second moment EQ

θ [p̂∆ (v, w; θ)] can be evaluated using a variant of

Algorithm 5.1.

6. Simulated likelihood estimators. This section analyzes the asymptotic behavior of the simulated likelihood estimator of the parameter θ of the

jump-diffusion process X. Let p̂K

∆ be a transition density estimator based on

K ∈ N Monte Carlo samples of (13). The simulated likelihood function of

6

One

could

also

choose

“locally”

optimal

parameters

by

solving

2

min`,L>0,ρ∈R EQ

[p̂

(v,

w;

θ)]R(v,

w;

θ)

for

each

(v,

w;

θ).

However,

this

may

be

com∆

θ

putationally burdensome.

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

17

Q

K

θ at the data X is given by L̂K (θ) = m

n=1 p̂∆ (X(n−1)∆ , Xn∆ ; θ); this is the

Monte Carlo counterpart of L(θ) is Section 2. A simulated maximum likeliK satisfies almost surely θ̂ K ∈ arg max

K

hood estimator (SMLE) θ̂m

θ∈Θ L̂ (θ).

m

Conveniently, the maximization of the simulated likelihood is effectively

a deterministic optimization problem. We draw K Monte Carlo samples of

the basic random variate R to construct the density estimator p̂K

∆ (v, w; θ);

see Section 5. Because p̂K

(v,

w;

θ)

is

a

deterministic

function

of

(v, w, θ)

∆

given the samples of R, it can be evaluated at various data points (v, w) =

(X(n−1)∆ , Xn∆ ) without re-simulation. Thus, given the samples of R and the

data X, the likelihood L̂K (θ) is a deterministic function of the parameter

θ. There is no need to re-simulate the likelihood during the optimization,

eliminating the need to deal with a simulation optimization problem.

K . We first establish that θ̂ K is

We study the properties of a SMLE θ̂m

m

asymptotically unbiased. A sufficient condition for this property is that

limK→∞ L̂K (θ) = L(θ) almost surely and uniformly over the parameter

space Θ. The strong law of large numbers and the continuous mapping theorem imply that the above convergence occurs almost surely in our setting,

but they do not provide uniformity of the convergence. We use the strong law

of large numbers for random elements in separable Banach spaces to prove

uniform convergence, exploiting the compactness of the parameter space Θ

and the fact that L̂K takes values in a separable Banach space (see, e.g.,

Beskos, Papaspiliopoulos and Roberts (2009) and Straumann and Mikosch

(2006)). Conveniently, asymptotic unbiasedness implies (strong) consistency

of a SMLE if a MLE is (strongly) consistent.

18

Theorem 6.1.

suppose that:

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

Suppose the conditions of Theorem 3.1 hold. Moreover,

h

i

(C1) For any v, w ∈ S, E supθ∈Θ p̂∆ (v, w; θ) < ∞.

K is an asymptotically unbiased estimator of θ̂ , i.e.,

Then any SMLE θ̂m

m

K

θ̂m → θ̂m almost surely as K → ∞. If a MLE θ̂m is (strongly) consistent,

K is also a (strongly) consistent estimator of the true paramthen a SMLE θ̂m

K → θ ∗ in P ∗ -probability

eter θ∗ if K → ∞ as m → ∞. In other words, θ̂m

θ

(almost surely) as m → ∞ and K → ∞.

Theorem 6.1 states that, for a given realization of the data X, a SMLE

K converges to a theoretical MLE as the number of Monte Carlo samples

θ̂m

K → ∞. This implies that a SMLE inherits the consistency of a MLE if more

Monte Carlo samples are used as more data becomes available (see Appendix

A for sufficient conditions for consistency of a MLE). Condition (C1) is mild,

and implies that the simulated likelihood is bounded in expectation.

How many Monte Carlo samples K of the density estimator (13) need to

be generated for each additional observation of X? In general, the number

of samples will influence the variance of the density estimator and this will

affect the asymptotic distribution of a SMLE. Standard Monte Carlo theory

asserts that the error from approximating the true transition density p∆

−1/2 ). Thus, the Monte Carlo error

by the estimator p̂K

∆ is of order O(K

K

arising from using p̂∆ instead of p∆ for a single observation vanishes as

K → ∞. However, the aggregate Monte Carlo error associated with the

simulated likelihood function L̂K (θ) may explode as m → ∞ if K is not

chosen optimally in accordance with m. The following theorem indicates

the optimal choice of K.

Theorem 6.2. Suppose the conditions of Theorem 6.1 hold, and assume

the conditions of Corollary 4.2 for differentiation up to second order. In

addition, suppose the following condition holds.

(C2) The mapping θ 7→ p∆ (v, w; θ) is three-times continuously differentiable

for any v, w ∈ S.

(C3) There exists a deterministic matrix Σθ∗ of full rank such that the following limit holds in Pθ∗ -distribution as m → ∞: √1m ∇ log L(θ∗ ) →

N (0, Σθ∗ ).

1 2

(C4) The equality Σθ∗ = − limm→∞ m

∇ log L(θ∗ ) holds in Pθ∗ -probability

for Σθ∗ from Condition (C3).

h i

p̂∆ (v,w;θ)

(C5) For any θ ∈ int Θ, supv,w∈S VarQ

∇

< ∞.

θ

p∆ (v,w;θ)

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

19

m

K is asympIf K

→ c ∈ [0, ∞) as m → ∞ and K → ∞, then a SMLE θ̂m

√

−1

K − θ ∗ ) → N 0, Σ

in Pθ∗ -distribution

totically normal. That is, m(θ̂m

θ∗

m

as m → ∞ and K → ∞. On the other hand, if K → ∞ as m → ∞ and

√

K − θ ∗ ) → 0 almost surely.

K → ∞, then K(θ̂m

Conditions (C3) and (C4) imply asymptotic normality of a MLE θ̂m

−1

with asymptotic variance-covariance matrix Σ−1

θ∗ ; i.e., θ̂m → N (0, Σθ∗ ) as

m → ∞. A SMLE inherits this asymptotic normality property if the density

m

estimator satisfies (C5) and K

converges to some finite constant. There is

no loss of efficiency when estimating θ using the simulated likelihood rather

than the theoretical likelihood. The Monte Carlo variance does not impact

the asymptotic distribution of a SMLE. If the number of Monte Carlo samples K grows fast enough, then the Monte Carlo variance vanishes in the

limit as m → ∞. This is guaranteed by the choice K = O(m).

Sufficient conditions for differentiability of the density p∆ are given in

Proposition 3.2. Sufficient conditions for (C3) and (C4) are given in Appendix A. Condition (C5) is mild but necessary. It implies that the variance

of the simulated score function is finite. Sufficient conditions for (C5) are

given in Table 2.

That our Monte Carlo approximation of the transition density does not

affect the asymptotic distribution of the estimator is a consequence of the

unbiasedness of our density approximation. To appreciate this feature, consider a conventional Monte Carlo approximation of the transition density,

where one first approximates X on a discrete-time grid and then applies a

nonparametric kernel to the Monte Carlo samples. In the special case of a

diffusion that is approximated using an Euler scheme, Detemple, Garcia and

Rindisbacher (2006) show that this approach distorts the asymptotic distriEuler denote the

bution of the likelihood estimator. More precisely, letting θ̂m

estimator obtained from Km i.i.d. Monte Carlo samples of the Euler approximation of X∆ that are based on km discretization steps, Theorem 12

of Detemple, Garcia and Rindisbacher (2006) implies that if Km → ∞ and

√

Euler − θ ∗ ) → N β, ΣEuler as m → ∞ in

km → ∞ as m → ∞, then m(θ̂m

Pθ∗ -distribution, where either β 6= 0 or ΣEuler 6= Σ−1

θ∗ . In particular, Detemple, Garcia and Rindisbacher (2006) show that β = 0 and ΣEuler = Σ−1

θ∗ cannot hold simultaneously. Thus, this approach either generates size-distorted

asymptotic standard errors or is inefficient.7 Our exact Monte Carlo approach, in contrast, facilitates efficient parameter estimation and produces

7

Efficiency can be achieved if the number of Euler discretization steps

√km is chosen according to the square-root rule of Duffie and Glynn (1995), i.e., km = O( Km ). Detemple,

Garcia and Rindisbacher (2006) develop an improved discretization scheme for diffusions

for which β = 0. For jump-diffusions with state-independent coefficients, Kristensen and

20

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

correct asymptotic standard errors at the same time. It eliminates the need

to discretize X, and generates an estimator that has the same asymptotic

distribution as a true MLE.

7. Numerical results. This section illustrates the performance of the

density and simulated likelihood estimators. We consider two alternative

models. The first is the mean-reverting interest rate model of Das (2002).

We specify the jump-diffusion SDE (1) by choosing the following functions

for θ = (κ, X̄, σ, l0 , l1 , γ1 , γ2 ) ∈ R+ × R × R3+ × R × R+ , x ∈ S = R, and

d ∈ D = R: µ(x; θ) = κ(X̄ − x), σ(x; θ) = σ, Γ(x, d; θ) = γ1 + γ2 d, and

Λ(x; θ) = l0 + l1 x. The jump-diffusion X has dynamics

(15)

dXt = κ(X̄ − Xt )dt + σdBt + dJt ,

PNt

where Jt =

n=1 (γ1 + γ2 Dn ) and N is a counting process with statedependent intensity λt = l0 + l1 Xt . The marks (Dn )n≥1 are i.i.d. standard normal. We choose the parameter space as Θ = [0.0001, 3] × [−1, 1] ×

[0.0001, 1] × [0.0001, 100] × [−10, 10] × [−0.1, 0.1] × [0.0001, 0.1]. The true

parameter θ∗ is taken as (0.8542, 0.0330, 0.0173, 54.0500, 0.0000, 0.0004,

0.0058) ∈ int Θ, the value estimated by Das (2002) from daily data of the

Fed Funds rate between 1988 and 1997.8 We take X0 = X̄ = 0.0330.

The second model we consider is the double-exponential stock price model

of Kou (2002). For this model, we set θ = (µ, σ, l0 , l1 , p, γ1 , γ2 ) ∈ R × R+ ×

R2+ ×[0, 1]×R2+ , x ∈ S = R+ , d ∈ D = R2+ ×[0, 1], µ(x; θ) = µx, σ(x; θ) = σx,

Λ(x; θ) = l0 + l1 x, and

x(ed1 − 1),

if d3 < p,

Γ(x, d; θ) =

x(e−d2 − 1), otherwise.

This results in a jump-diffusion X with dynamics

(16)

dXt = µXt− dt + σXt− dBt + Xt− dJt

P t Un

with Jt = N

− 1) for a counting process N with state-dependent

n=1 (e

intensity λt = `0 + `1 Xt . The random variable Un has an asymmetric

(1)

(3)

double exponential distribution with Un = Dn if Dn < p, and Un =

(2)

(1)

(2)

(3)

−Dn otherwise, for a mark variable Dn = (Dn , Dn , Dn ) that satisfies

(1)

(2)

(3)

Dn ∼ Exp(1/η1 ), Dn ∼ Exp(1/η2 ), and Dn ∼ Unif[0, 1]. We choose

Θ = [−1, 1] × [0.0001 × 1] × [0.0001, 100] × [−1, 1] × [0.001, 100]2 . The true

Shin (2012) show that β = 0 can be achieved under conditions on the kernel.

8

Das (2002) assumed l1 = 0.

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

21

parameter is θ∗ = (0.15, 0.20, 10, 0, 0.3, 1/0.02, 1/0.04) ∈ int Θ, which is

consistent with the choice of Kou (2002). We take X0 = 10.

Model (15) is affine in the sense of Duffie, Pan and Singleton (2000), allowing us to compute the “true” transition density of X by Fourier inversion

of the characteristic function of X. For Model (16), only the process log X

is affine. We can nonetheless recover the transition density of log X in semianalytical form via Fourier inversion, and then compute the density of X via

a change of variables. The density estimators derived from Fourier inversion

in these ways serve as benchmarks for Models (15) and (16).

We implement the Fourier inversion via numerical quadrature with 103

discretization points in [−103 , 103 ]. The characteristic functions of X in

Model (15) and log X in Model (16) are known in closed form if l1 = 0.

When l1 6= 0, the characteristic functions solve sets of ordinary differential

equations that need to be solved numerically. We use a Runge-Kutta method

based on 50 time steps to numerically solve these differential equations.

The numerical results reported below are based on an implementation in

R, running on an 2×8-core 2.6 GHz Intel Xeon E5-2670, 128 GB server at

Boston University with a Linux Centos 6.4 operating system. All R codes

are available for download at http://people.bu.edu/gas.

7.1. Transition density estimator. We begin by evaluating the accuracy

∗

of the unbiased density (UD) estimator. Figures 1, 2, and 3 show p̂K

∆ (X0 , w; θ )

1 1 1

for Models (15) and (16), ∆ ∈ { 12 , 4 , 2 }, and each of several K, along with

pointwise empirical confidence bands obtained from 103 bootstrap samples.9

We compare the UD estimator with several alternatives:

• A Gaussian kernel estimator obtained from K samples of X∆ generated

with the exact method of Giesecke and Smelov (2013).

• A Gaussian kernel estimator obtained from K samples of X∆ generated with the discretization method of Giesecke

√ and Teng (2012). The

number of discretization steps is taken as K, as suggested by the

results of Duffie and Glynn (1995).

The UD estimator oscillates around the true transition density, which is

governed by the expectation Ψ∆ in (7). The expectation Ψ∆ can be viewed

as a weighted sum of infinitely many normal distributions with variance

TN∆ . The UD estimator approximates this infinite sum by a finite sum. The

oscillations of p̂K

∆ correspond to the normal densities that are mixed by the

UD estimator (13). The amplitude of the oscillations of p̂K

∆ is large for small

9

We find that the solutions of (14) yielding optimal configurations of the density estimator are ` = 58.18, L = 3.65 and ρ = 0.02 for Model (15) and ` = 21.92, L = 7.38, and

ρ = 0.06 for Model (16). The optimizations were solved using the Nelder-Mead method.

22

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

K = 1000

0

10

20

30

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Euler)

Kernel (Exact)

0.00

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.10

K = w5000

0

10

20

30

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Euler)

Kernel (Exact)

0.00

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.10

K = 10000

w

0

10

20

30

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Euler)

Kernel (Exact)

0.00

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.10

∗

Fig 1. Estimator p̂K

∆ (X0 , w; θ ) for Model (15) with K ∈ {1000, 5000, 10000}, w ∈ [0, 0.1]

and ∆ = 1/12, along with 90% bootstrap confidence bands, as well as the true transition

density and kernel estimators obtained from Euler’s method and exact simulation.

values of K. As K increases, the amplitude of the oscillations decreases and

the confidence bands become tight. This confirms the unbiasedness result of

Theorem 4.1. If the number K of Monte Carlo samples is sufficiently large,

the UD estimator p̂K

∆ accurately approximates the transition density over

the entire range of X. In contrast, both kernel density estimators are biased.

The biases are relatively large in the tails of the distribution; see Figure 2.

They are also large when the time ∆ between consecutive observations is

23

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

1e−05

1e−03

1e−01

K = 1000

1e−09

1e−07

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Exact)

Kernel (Euler)

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

11

12

13

11

12

13

1e−05

1e−03

1e−01

K = w5000

1e−09

1e−07

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Exact)

Kernel (Euler)

7

8

9

10

1e−05

1e−03

1e−01

K = 10000

w

1e−09

1e−07

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Exact)

Kernel (Euler)

7

8

9

10

∗

Fig 2. Estimator p̂K

∆ (X0 , w; θ ) for Model (16) with K ∈ {1000, 5000, 10000}, w ∈ [0, 0.1]

and ∆ = 1/12, along with 90% bootstrap confidence bands, as well as the true transition

density and kernel estimators obtained from Euler’s method and exact simulation. The

y-axis in this plot is displayed in log scale.

large, as can be seen in Figure 3.

By construction, our density estimator respects the boundary of the state

space S. That is, our density estimator assigns no probability mass to values

outside of S. Figure 4 illustrates this property for Model (16), in which

X has the bounded state space S = [0, ∞). The 90% confidence bands of

p̂∆ (X0 , w; θ∗ ) are tight and close to zero for very small values of w regardless

24

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

∆ = 0.25 (log scale)

0.0

1e−10

0.1

1e−06

0.2

0.3

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Exact)

Kernel (Euler)

1e−02

0.4

∆ = 0.25

6

8

10

12

14

16

6

8

12

14

16

0.00

1e−10

0.10

1e−06

0.20

1e−02

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Exact)

Kernel (Euler)

0.30

10

∆ = 0.5 (log

w scale)

∆ =w0.5

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

∗

1 1

Fig 3. Estimator p̂K

∆ (X0 , ·; θ ) for Model (16) with K = 1000, X0 = 10, and ∆ ∈ { 4 , 2 },

along with 90% bootstrap confidence bands, as well as the true transition density and kernel

estimators obtained from Euler’s method and exact simulation. The y-axes of the right plots

are displayed in log scale.

of the size of X0 . Although not displayed in Figure 4, we know that the

Gaussian kernel estimator derived from exact samples of X∆ will also restrict

itself to S. If the samples are derived from Euler’s method, then the Gaussian

kernel estimator may not satisfy this property because Euler’s method does

not ensure that the approximate solution of the SDE (16) will stay within

the state space S.

Figure 4 also shows that our density estimator is always non-negative.

This property holds because our estimator is a mixture of Gaussian densities

and the weights are non-negative. Although not displayed, the kernel density

estimators are also always non-negative. However, Figure 4 shows that the

Fourier inverse estimator may become negative for extreme values of the

state space S. This occurs because the numerical inversion of the Fourier

transform may become numerically unstable in certain situations.

7.2. Computational efficiency. We run three experiments to assess the

computational efficiency of our UD estimator. We start by analyzing the con-

25

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

X0 = 0.01

−1010

0.00

0.05

0.10

−200

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

−10100

−20 0

20

200

40

60

600

X0 = 0.1

0.15

0.000

0.005

0.010

0.015

X0 = 0.0001

w

−101000

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

0.0000

0.0005

0.0010

0.0015

−1010000

−2000

0

2000

40000

6000

X0 = w0.001

UD

Confidence bands

Fourier inversion

0.00000

0.00005

0.00010

0.00015

∗

Fig 4. Estimator p̂K

∆ (X0 , ·; θ ) for Model (16) with K ∈ {1000, 5000, 10000}, X0 ∈

{0.1, 0.01, 0.001, 0.0001}, and ∆ = 1/12, along with 90% bootstrap confidence bands, as

well as the true transition density.

vergence of the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) of the estimator p̂K

∆ (v, w; θ)

at a random parameter θ and 120 randomly selected points (v, w). The

bias of the RMSE is computed relative to the “true” density obtained by

Fourier inversion. We take ∆ = 1/12 for Model (15) and ∆ = 1/4 for

Model (16). Repeated calculations of the transition density at the points

(v, w) = (X(n−1)∆ , Xn∆ ) are required for evaluating the likelihood. Thus,

our analysis also indicates the efficiency of computing the likelihood given

10 years of monthly data for Model (15), and 30 years of quarterly data

for Model (16). Figure 5 shows the RMSE of p̂K

∆ (v, w; θ) as a function of

the time required to evaluate the estimator at a randomly selected θ ∈ Θ

and 120 randomly selected pairs (v, w) ∈ [0, 0.1]2 . It also shows the RMSE

for the alternative estimators discussed above. The UD estimator has the

fastest error convergence rate. It also has the smallest RMSE when the time

between observations is small or when the available computational budget

is large, consistent with the asymptotic computational efficiency concept of

Glynn and Whitt (1992).

Next, we study the computational effort required estimate the likelihood

for different sample sizes. To this end, we select a random parameter θ ∈ Θ

and m random pairs (v, w) ∈ [0, 0.1]2 , and measure the average time it takes

3

to evaluate p̂K

∆ (v, w; θ) across all m pairs (v, w) for ∆ = 1/12 and K = 10 .

26

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

1.0

Kernel (Euler)

K = 750

K = 500

Kernel (Exact)

K = 1000

UD

K = 2500

0.5

RMSE (log scale)

2.0

K = 45

K = 5000

K = 5000

K = 10000

K = 15000

2

5

10

20

Run time (in mins, log scale)

0.030 0.040

0.015 0.020

RMSE (log scale)

(a) Model (15), ∆ = 1/12.

Kernel (Exact)

K = 50

K = 1000

UD

K = 100

K = 500

Kernel (Euler)

K = 1000

K = 500

K = 5000

K = 1000

K = 5000

K = 10000

K = 15000

1

2

5

10

20

K = 10000

50

100

Run time (in mins, log scale)

(b) Model (16), ∆ = 1/4.

Fig 5. Root-mean-squared error (RMSE) of different density estimators as a function of computation time. The RMSE is the square root of the average squared error of an estimator of p∆ (v, w; θ) over 120 randomly selected pairs (v, w) and a randomly selected parameter θ. For Model (15) with ∆ = 1/12, we randomly select

(v, w) ∈ [0, 0.1]2 and θ = (0.9924, 0.0186, 0.0345, 32.6581, 2.3996, 0.0006, 0.0039) ∈ Θ.

For Model (16) with ∆ = 1/4, we randomly select (v, w) ∈ [5, 15]2 and θ =

(−0.1744, 0.2342, 28.4388, 0.5418, 0.9278, 80.8277, 69.6841) ∈ Θ.

Figure 6 shows the average run time as a function of m for Model (15). It also

compares our average run times to the average run times associated with

alternative density estimators. Our density estimator involves the smallest

per-observation cost when evaluating the likelihood for a given m. Further,

the per-observation cost decreases as m grows. Similar findings hold for

Model (16), and for alternative choices of ∆.

The UD estimator performs well in these first two experiments for two reasons. First, the samples of the basic random variates R used to compute the

density estimator (see Section 5) need to be generated only once. They can

27

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

10

5

2

Fourier inversion

Kernel (Euler)

1

Per−observation run time (in secs, log scale)

Kernel (Exact)

UD

50

100

200

500

Sample size m (log scale)

Fig 6. Per-observation run time required to compute the likelihood of Model (15)

with different density estimators as a function of the sample size m. The perobservation run time is measured as the average time necessary to estimate the density p∆ (v, w; θ) at m randomly selected pairs (v, w) ∈ [0, 0.1]2 for ∆ = 1/12 and

θ = (0.9924, 0.0186, 0.0345, 32.6581, 2.3996, 0.0006, 0.0039) selected randomly from Θ. We

take K = 1000 for the UD estimator. For the Kernel (Euler) estimator, we use 1000 Euler

samples of X∆ as to achieve roughly the same RMSE (see Figure 5). Due to computational

constraints, for the Kernel (Exact) estimator we use only 500 exact samples of X∆ .

be reused to compute p̂K

∆ (v, w; θ) for any v, w ∈ S and any θ ∈ Θ. This yields

the small and decreasing per-observation cost for estimating the likelihood.

Second, our density estimator is unbiased. Alternative estimators do not

exhibit both of these properties. Kernel density estimation introduces bias,

which slows down the rate of convergence for the RMSE. Euler discretization

introduces additional bias. As a result, the discretization-based density estimator has the slowest rate of convergence. For the other simulation-based

estimator, which is based on exact samples of X∆ , the samples of the process

must be re-generated for every pair (v, w) at which the transition density

is estimated. This increases computational costs. Finally, the Fourier density estimator of Duffie, Pan and Singleton (2000) is essentially error-free.

However, evaluating this estimator requires numerically solving a system

of ordinary differential equations for each pair (v, w), which increases the

computational costs.

A Monte Carlo estimator of the density has the implicit benefit that it

28

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

Table 1

Run times of the different operations necessary to compute the density estimator

p̂K

∆ (v, w; θ) for Model (15) at a random parameter θ ∈ Θ and 120 random

(v, w) ∈ [0, 0.1]2 using Kp processors.

Generating K i.i.d. samples of R

Computing one sample of p̂∆ given R

Computing p̂K

∆ given K samples of R for K = 1000

Total run time in seconds

Speed-up factor

1

9.84

0.10

98.86

108.70

Processors Kp

2

4

9.84

9.84

0.10

0.10

53.64 31.93

63.48 41.77

1.71

2.60

6

9.84

0.10

27.19

37.03

2.94

can be computed in parallel using multiple processors. If a density estimator

requires K i.i.d. Monte Carlo samples and Kp processors are available, then

each processor only needs to compute KKp Monte Carlo samples. We analyze

the computational gains generated by parallel computing our density estimator. For Model (15), we measure the time it takes to generate K = 1000

i.i.d. samples of the basic random variates R and parallel compute p̂∆ (v, w; θ)

at a random parameter θ ∈ Θ and 120 random pairs (v, w) ∈ [0, 0.1]2 using

Kp ∈ {1, 2, 4, 6} processors. Table 1 shows that parallelization results in a

significant reduction of the run time necessary to evaluate our density estimator. Increasing the number of processors from 1 to 4 reduces the total

run time by a factor of 2.6. There are other possibilities to further reduce

the run time required to evaluate our UD estimator. Graphics processing

units (GPUs) may be used, for example.

7.3. Simulated likelihood estimators. A Monte Carlo analysis illustrates

the properties of the simulated maximum likelihood estimators (SMLE).

We generate 100 samples of the data X = {X0 , X∆ , . . . , Xm∆ } from the

law Pθ∗ for m = 600 and ∆ = 1/12 for Model (15), and m = 400 and

∆ = 1/4 for Model (16) using the exact algorithm of Giesecke and Smelov

(2013). This corresponds to 50 years of monthly data for Model (15) and 100

years of quarterly data for Model (16). For each data sample, we compute

K by maximizing the simulated likelihood L̂K , and an MLE

an SMLE θ̂m

θ̂m by maximizing the likelihood obtained from the true transition density.

The Nelder-Mead method, initialized at θ∗ , is used to numerically solve the

optimization problems. In accordance with Theorem 6.2, we choose K =

10m for Model (15) and K = 15m for Model (16) in order to guarantee

asymptotic normality of the SMLE.

We verify the conditions that imply consistency and asymptotic normality. We first check that the conditions of Appendix A for consistency and

29

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

Table 2

Sufficient conditions for consistency and asymptotic normality as stated in Theorems 6.1

(k)

and 6.2, and Appendix A. We choose K = 1000 and m = 600. Here, (p̂∆ )1≤k≤K are

i.i.d. samples of the density estimator p̂∆ , and (Xn∆ )0≤n≤m is generated from Pθ .

Panel A

Proxy

Condition

(A2)

supθ∈Θ,1≤n≤m p̂K

∆ (X(n−1)∆ , Xn∆ ; θ) < ∞

(A3)

2

supθ∈Θ,1≤i≤r,1≤n≤m (∂i p̂K

∆ (X(n−1)∆ , Xn∆ ; θ)) < ∞

2 K

2

∂i,j p̂∆ (X(n−1)∆ ,Xn∆ ;θ)

supθ∈Θ,1≤i,j≤r,1≤n≤m

<∞

p̂K (X

,X

;θ)

(A4)

∆

(n−1)∆

n∆

(m)

(A6)

inf θ∈Θ 1{Σ̂(m) is positiv definite} = 1 for Σ̂θ

θ

as defined in (A-5) in Appendix A

2

(k)

(v,w;θ)

k=1 p̂

2 < ∞

supθ∈Θ,v,w∈[0,0.1]2 1 PK ∆

(k)

p̂

(v,w;θ)

k=1 ∆

K

2

P

(k)

K

1

k=1 ∂i p̂∆ (v,w;θ)

2

supθ∈Θ,1≤i≤r,v,w∈[0,0.1]2 K1 PK

(k)

∂ p̂

(v,w;θ)

k=1 i ∆

K

1

K

(C5)

Satisfied by:

Model (15)

Model (16)

Model (15)

Model (16)

Model (15)

Model (16)

Model (15)

Model (16)

PK

and

Model (15)

<∞

Model (16)

asymptotic normality of a MLE are satisfied. We can verify the conditions

using our density estimator p̂K

∆ . The analysis in Section 7.1 indicates that the

density estimator is a finite mixture of Gaussian densities. As a result, our

density estimator is three-times continuously differentiable, and Assumptions (A1) and (A5) of Appendix A are valid given that Θ is compact. Table

2 summarizes our procedure to evaluate the remaining conditions of Appendix A, and indicates that these conditions are satisfied. As a result, a

MLE is consistent and asymptotically normal. Next, we verify the conditions

of Theorems 6.1 and 6.2 implying consistency and asymptotic normality of

a SMLE. Table 2 shows that Condition (C5) is satisfied. Condition (C1) is

naturally satisfied because Θ is compact and p̂∆ is continuous. Conditions

(C2)-(C4) are also satisfied as implied by the conditions of Appendix A.

Thus, a SMLE is also consistent and asymptotically normal with the same

variance-covariance matrix as a MLE.

We test asymptotic unbiasedness of a SMLE (Theorem 6.1). Table 3 comK − θ̂ ] of a SMLE from a MLE to the average

pares the average deviation E[θ̂m

m

deviation (E[(θ̂m − θ∗ )2 ])1/2 of a MLE from the true parameter, for Model

(15) with ∆ = 1/12 in Panel A, and Model (16) with ∆ = 1/4 in Panel B.

The expectations are estimated by sample averages across all 100 data sets.

The values in Table 3 show that the average “error” of a SMLE is small

when compared to the average error of a MLE. The null hypothesis that the

error of a SMLE is equal to zero cannot be rejected for any model parameter

over any horizon based on the asymptotic distribution implied by Theorem

30

GIESECKE AND SCHWENKLER

Table 3

Average deviation of a SMLE from a MLE and average deviation of a MLE from the

true parameter θ∗ over all 100 data samples for Models (15) and (16).

k

X̄

σ

l0

l1

γ1

γ2

µ

σ

l0

l1

p

η1

η2

Model (15), ∆ = 1/12

m = 120, K = 1200

m = 600, K = 6000

K

K

E[θ̂m

− θ̂m ] (E[(θ̂m − θ∗ )2 ])1/2

E[θ̂m

− θ̂m ] (E[(θ̂m − θ∗ )2 ])1/2

0.0867

0.3627

0.2418

0.4296

0.0093

0.1739

−0.0506

0.1161

0.0071

0.0173

0.0088

0.0154

0.1192

3.2255

0.4691

2.5916

−1.9035

3.7097

−2.4162

4.1564

0.0000

0.0019

0.0005

0.0008

0.0012

0.0027

0.0003

0.0016

Model (16), ∆ = 1/4

m = 200, K = 3000

m = 400, K = 6000

K

K

E[θ̂m

− θ̂m ] (E[(θ̂m − θ∗ )2 ])1/2

E[θ̂m

− θ̂m ] (E[(θ̂m − θ∗ )2 ])1/2

0.0934

0.3465

0.1469

0.2987

0.1259

0.1618

0.2524

0.2293

−0.4477

12.8842

13.9345

14.2461

−0.1977

0.8127

−0.2395

0.8247

0.0623

0.3797

0.2956

0.3907

1.0535

14.1629

−1.2553

18.1835

−1.7469

9.4348

−6.7299

12.1261

6.2. This verifies the asymptotic unbiasedness property.

We analyze the finite-sample distribution of a SMLE. Tables 4 and 5

√

K−

compare the mean and the standard deviation of the scaled errors m(θ̂m

√

∗

∗

θ ) for a SMLE and m(θ̂m − θ ) for a MLE across all 100 data sets for

Models (15) and (16). They also indicates the theoretical asymptotic means

√

K − θ ∗ ) and √m(θ̂ − θ ∗ ) in accordance

and standard deviations of m(θ̂m

m

with Theorem 6.2. For most parameters, the moments of the scaled error of a

SMLE are similar to the corresponding moments of the scaled error of a MLE

over all time horizons for both models. Based on the asymptotic standard

errors indicated in the column “Asymp.” of Table 4, we cannot reject the

null hypothesis that the differences between the scaled error moments of

a SMLE and a MLE are equal to zero for any value of m. This tells us

that the finite-sample distribution of a SMLE is similar to the finite-sample

distribution of a MLE.

Next, we consider the asymptotic distribution of a SMLE. According to

Theorem 6.2, a SMLE and a MLE share the same asymptotic normal distribution with mean zero and variance-covariance matrix Σ−1

θ∗ . As a result,

we expect that the differences between the means and the standard devia√

K − θ ∗ ) and √m(θ̂ − θ ∗ ) decrease as m increases. We find

tions of m(θ̂m

m

SIMULATED LIKELIHOOD FOR JUMP-DIFFUSIONS

31

Table 4

√

K

Empirical means (“M”) and standard deviations (“SD”) of the scaled error m(θ̂m

− θ∗ )

√

∗

of a SMLE and the scaled error m(θ̂m − θ ) of a MLE, over 100 independent data

samples for Model (15) with ∆ = 1/12. The table also shows the differences (“Diff.”)

between the sample moments of the scaled errors of a SMLE and a MLE, as well as the

average asymptotic moments (“Asymp.”) of a SMLE in accordance with Theorem 6.2.

The asymptotic mean is zero, the asymptotic standard deviations are given by the average

of the square-roots of the diagonal entries of Σ−1

θ ∗ in Theorem 6.2 across all 100 data sets.

√

√

m(k̂ − k∗ )

ˆ − X̄ ∗ )

m(X̄

√

m(σ̂ − σ ∗ )

√

√