Journal of Globalization and Development Impact of Political Reservations in West

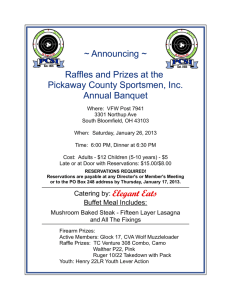

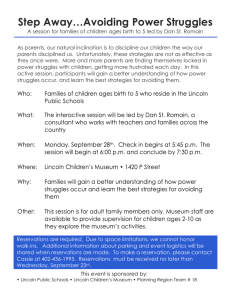

advertisement