Anxiety, Advice, and the Ability to Discern: Feeling Anxious Motivates

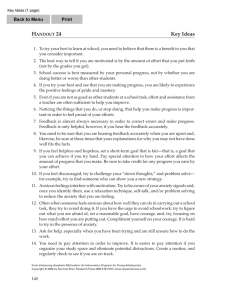

advertisement