Trade A simple model of trade

advertisement

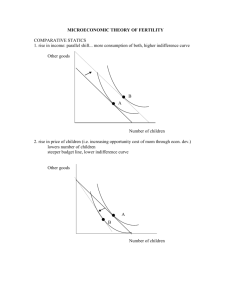

Trade A simple model of trade Let us first consider a country that does not trade with any other countries. It produces two goods, agricultural and industrial products. The more agriculture it has, the less industrial products it can produce as more resources will have to be devoted to agricultural production. We can show the production possibility of the country in the following figure: Ind. Agric Any point on or inside the curve is feasible; points outside the curve are not feasible. To describe preferences, we look at a typical (representative) consumer who likes both agricultural and industrial products. However, she likes to mix, so she prefers to have both some agric and some ind, rather than only one of the two or a very disproportionate share. We can then show her preferences using indifference curves. An indifference curve goes through all combinations of agric and ind such that our consumer is equally well of. To put it another way, she is indifferent between all points on the indifference curve. U0 is one indifference curve. Because we have assumed that consumers like to mix, it is curved towards to origin. U1 is another indifference curve, which depicts a higher level of utility. That means points on U1 are better than points on U0. Ind. U 1 U 0 Agric We can now use the indifference curves to find which feasible combination of agric and ind that is preferred by consumers. To do this, we put the two figures together: Ind. X Y Z U 2 U 1 U 0 Agric Let us first consider the point X, which is on the production possibility frontier, and the indifference curve U0 is crossing the frontier. Now another possibility may be Y, which is also on the frontier. U1 goes through this point. As U1 is further out than U0, points on U1 are better than points on U0. This means that Y is better than X, so X will not be chosen. But using the same reasoning, Y will not be chosen either. We can go further out until we come to Z, where the production possibility frontier and the indifference curve U2 are tangents. Here, there is no feasible point that will be better, so this is the optimal point in a closed economy. One way to obtain this outcome is through a market mechanism. If we have a line going through Z such that it is tangential to the indifference curve and the production possibility frontier, the slope of this curve can be interpreted as the relative price of agricultural products relative to industrial products in the sense that the steeper the curve is, the more agricultural products are expensive. Now a consumer facing such prices would still choose the point Z even though she has no clue about the production possibility frontier. To se this, she believes she can choose any point below the price line. Again, she wants the line and the indifference curve to cross, which is the case in the point Z. Ind. X Y Z U 2 U 1 U 0 Agric Let us now look at what happens if we open up for trade. Generally, the price level abroad will be different from the price level at home, so both consumer and producers face new prices. This means that the price line will have a different slope. Producers adjust first so the new price line is tangential to the production possibility frontier (this will maximize profits). Then consumers will locate on this new price line where their indifference curves are tangential to the price line. Ind. I c I p A c A p Agric Now production is Ap and Ic while consumption is Ac and Ic. Also exports of agricultural products is the difference Ap - Ac and imports of industrial goods is Ic -Ic. Distribution in the model of trade So far we have only talked about economies where everybody is the same. However, an important problem with free trade is that some groups may be worse off although we also know that there are groups that are better off. Consider a case where agricultural products are produced using labour and land while industrial products are produced using labour and capital. For simplicity, we assume that land and capital owners do not work and workers own no land or capital. After we open for free trade, the price of agricultural products relative to industrial products rise (the price line gets steeper), so the agricultural sector gets more profitable and the industrial sector less. w A L A L w I w w’ The solid lines give the demand for labour in the agricultural and industrial sector. Assume that wages age given in units of food (as we don’t have any money here). The wage level before trade is found in the point where the two solid curves vross. This wage level is denoted w. When we open up for trade, the price of industrial goods relative to the price of food declines, so the industrial sector gets less profitable and its demand for labour declines. I The new demand for labour in the industrial sector is depicted by the dotted curve. We see that this leads to a lower wage in equilibrium, keeping in mind that wages are denoted in units of food. Hence after the opening up, workers can buy less food and more industrial products than they could before. Whether they are better or worse off depends on whether they mostly consume food or industrial goods. But if they are poor, they will mostly consume food, and are hence worse off. Also land owners are always better off and capital owners worse off. Furthermore, employment in agriculture increases and employment in the industry declines.