REPORT OF THE ACADEMIC SENATE TASK FORCE ON INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS

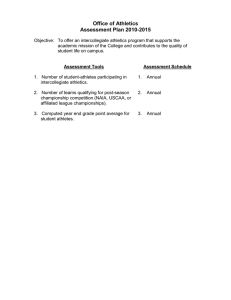

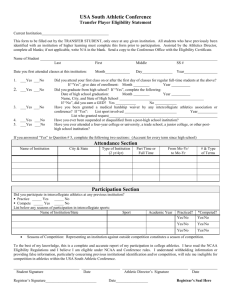

advertisement