How to document the creation of digital language resources

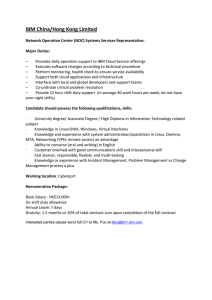

advertisement

How to document the creation of digital language resources

- a case study

Jan Engh

Oslo University Library, Norway

jan.engh@ub.uio.no

47 22 85 77 17

47 22 84 45 81 (fax)

Abstract Natural language processing is not only a question of new algorithms and new

technologies for representing linguistic data. It is also about how to enter and cater for

language data on a broad scale. This will still, to a great extent, imply conversion of

analogical sources and, in the case of many languages, completion and simply

registration of language information. Although these activities in general are a question

of development rather than research, such a seemingly trivial task may have its

theoretical challenges relating to the language involved. And, above all, no full-scale

natural language processing will be possible without it. However, while there is a

flourishing literature on the more formal aspects and the technical innovation part of

natural language processing, documentation on how the basic language resources were

and partly still are established is scarce, and existing documentation may be ignored. The

present article is a case study of the first full-scale encoding of the intricacies of the

Norwegian lexicon and morphology in a digital format. At the same time, it contains a

discussion as to how such projects could and ought to be documented, especially with a

view to prevent later conjectures and allegations about the origin of the resulting

resources. In doing so, it will provide a special insight into the often uneasy relationship

between linguistic research and development in private and public sector.

Keywords Natural language processing ∙ Language resource creation ∙ Lexicon ∙

Morphology ∙ Norwegian

1 Introduction

After decades of work, researchers and developers may now find more and more basic

linguistic resources available to them in what used to be called machine-readable format even for less important languages such as Norwegian and its two written standards. In

spite of the expanding activity of harvesting linguistic data from the internet and a

somewhat more positive attitude to put digital texts at the disposal for researchers on the

part of publishers,1 this still means that the major part of the language information

accessible has been converted from printed sources - or simply created by individual

1

See for instance The English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus at

http://www.hf.uio.no/ilos/english/services/omc/enpc/index.html [Accessed 27 March 2013].

1

linguists, drawing on their competences as native language users. In the latter case, one

may talk about completion or even registration of language data from scratch. In fact,

existing digital language resources are the result of a process where all the approaches are

involved, although to a varying degree.

Generally, such processes have been poorly documented. While there are conferences

and extensive publishing about how to build linguistic resources from data on the web,

hardly anything is said or written about how one actually went about creating digital

resources from printed or “innate” sources.2 This reflects the fact that this process suffers

from a certain lack of status in the research community for being a straightforward,

technical matter, and because “everybody” knows the language. However, the reason

may even be a sentiment that conversion and the less conspicuous completion and

registration are phenomena of the past, a task that has been accomplished once and for

all.3 In fact, it is a transitory phase of linguistics, since new resources are created in a

digital medium already from the start. So, in a way, this entire process belongs to the

Bronze Age of natural language processing. But that is exactly one of the reasons why the

creation of digital language resources needs to be documented. Not only as an important,

although transitory phase of linguistics as a discipline, but also for quality and legal

reasons: Documentation as to how and when the creation took place and by whom

provides important information about the quality of the product and what you can

reasonably expect from it. It is even important information from an intellectual property

point of view. Whose material is it anyway? Although nobody has the copyright of a

language, the value-adding processing of language information gives the producer certain

rights. Proper documentation may provide a lead as to what one can do with the material

as far as business is concerned, and what you can take academic credit for.

In addition to the technological and legal aspects of digitalisation, documentation of

the creation of digitalised language data may shed light on various aspects of a linguistic

nature: Even what appear to be the simplest conversions in the first place tend to reveal

vagueness and cases of doubt. In fact, few conversions are really that simple, especially

when a complex written material is concerned, implying the compilation of information

from sources as disparate as taped lists in various formats, printed dictionaries, printed

articles or monographs, typed or handwritten filing cards, as well as footnotes in the local

academy’s annual report and oral sources. In fact, conversion of linguistic resources

cannot be carried out in an entirely automatic way, in the sense of just converting what is

written or printed to a digital form without human intervention. In most cases,

conversions imply a completion process as well.

1.1 Resource creation – research and/or development?

During the process of conversion of non-digital language information, it is not

uncommon that consideable information is added too. This happens basically because the

computer is a pedant. It demands unambiguous, explicit data. Not only are errors

identified, implementation of morphological rules makes inadequacies, inconsequences,

and contradictions visible as well. As a consequence, the linguists and native language

users involved in the process have to carry out corrections, interpret the norm and make

2

3

One exception is Santos 1996. Interestingly, it is written by an engineer.

Although there are still quite a few printed dictionaries left to be converted, for instance.

2

extrapolations to cases the authors of the orthography never had in mind, only to detect

contradictions that must be resolved etc. Depending on the language structure and the

breadth and thoroughness of the lexicographical tradition, conversion entails completion.4

Also, one simply has to enter new words (lemmas), and the importance of completion in

connection with such registration is equally evident.

To be more explicit, the completion of information about a particular written

language may consist in various sub-operations: First of all, controlling whether the

traditional paradigms fit the inflected forms of the class of lexemes they are supposed to:

Does every lemma belonging to the same paradigm of traditional, usually history-based

morphology actually inflect according to the rule given? To the extent that such

information is not systematically provided in the morphology that is converted, it has to

be added. Furthermore, traditional morphology usually takes a lot for granted as far as

linguistic competence is concerned. Such knowledge has to be identified and stated

explicitly when morphological data are digitalised. How, is a matter of discretion.

During this process, one inevitably has to take a stand as far as the more peripheral

parts of paradigms and defective paradigms are concerned. This can be referred to as

raising morphological awareness: Do the words, or rather lexemes, have a complete

paradigm? Are all imaginable forms actually used, and, in the negative case, what

consequences ought to be drawn for the morphology? For instance, do all adjectives

compare? What adjectives require a periphrastic comparison, and when is it optional. Do

all past participles and adjectives derived from past participles have a complete paradigm

as far as attributive forms are concerned? What about regular past participles and

attributive forms? Not only is such information broadly ignored by standardisation

authorities, it even belongs to the very periphery of native language users’ knowledge of

their own language. The vagueness as to the “existence” of these forms matches their

infrequency. In this respect, creating digital language resources may represent an

investigation into the border areas of the language in question.

One practical consequence of completion will even be detecting obvious non-standard

lexemes or word forms that are frequently used. So, a by-product of the development of a

“descriptive” morphology is necessarily the exploration of the actual differences between

descriptive and normative linguistics in general for the language in question. Thus,

completion even means that normative linguistics become an object of investigation.

These aspects represent only a limited selection of possible completion tasks. In fact,

the ones mentioned above are some of the ways of completing the lexicon and the

morphology that are relevant for Norwegian.

After completion, enrichment of the linguistic information represents a natural next

step. By enrichment is meant adding all sorts of semantic and syntactic information to all

the lemmas of the lexicon and to particular inflected forms as well, in cases of divergence

between the lemma form and its word forms. Such information is usually not

systematically represented in printed dictionaries, if mentioned at all. And when it is, the

it tends to be inaccurate. For instance

4

Not to mention the feedback it may give to the relevant normalisation authority.

3

Valency of verbs and adjectives

Types of verb complements: Infinitives? With or without the infinitival marker?

Past participles that may occur in an attribute position5

The possibility of adjectives to be used in an attribute position and/or as a predicative

Adverbs that cannot form an adverb phrase alone, adverbs limited to certain positions

Nouns with, typically, an animate reference only etc.

Although “everybody” knows the language, even the native language linguist doesn’t

know everything about it, and, necessarily, has to rely on other sources for verification, as

already alluded to: Conferring with others – even with the codified experience of others

in terms of analogical media. The native language competence of the linguist is

complemented by written sources.

Even though completion is important in connection with the digitalisation of the

lexicon and the morphology of many languages, it is generally disparaged if not ignored

as a process by linguists without any experience from the field. One plausible explanation

is the relationship to normative linguistics. Although without directly performing

normative activities,6 it is necessary to study and to implement the standardisation of the

language in question. Now, normative linguistics is generally not well seen by theoretical

(descriptive) linguists. Another explanation is that descriptive morphology itself and,

especially lexicography, which represents the context of the morphology development,

are not particularly trendy parts of linguistics. Enrichment, on the other hand, seems to be

slightly more appealing, perhaps because of its closer relationship to semantics and

syntax, which have been the more fashionable parts of linguistics since the 1950s.

It goes without saying that although the bulk of the work behind the creation of

digital language resources can be characterised as development, the research component

can be strong,7 depending on the language and the corresponding linguistic culture. The

object of this research will not only be the standardisation of the language in question, but

even the language structure itself, especially to the extent that there are no adequate

description in advance e.g. of morphological sub-systems. Whether this research is

carried out as a part of industrial research and development or at a public sector research

institution is immaterial, as long as fundamental linguistic tenets are observed.

1.2 How to document natural language processing

No project of language resource creatin can document itself in the way that is customary

in linguistics as well as in computational linguistics literature. Here, the research work as

such and its documentation are woven together as the research is carried out in some sort

of spiral: One presents good arguments in favour of an algorithm or a rule, tests it against

new material, e.g. example sentences, and rejects or performs modifications whenever

necessary. Then, still new material is taken into consideration etc. This is a process that,

at least to some extent, is carried out during the writing process itself and the progression

of the text often reflects how the conception of the problem under scrutiny actually

developed. Or, at least, that is often the intention.

5

Contrary to common belief, this property is not automatically tied to valency, cf. Akø 1992.

The result of the inquiry may be used as input for standardisation, but that is irrelevant in this connection.

7

As even suggested by the title of Johannessen and Fjeld 2008.

6

4

Seen from a different angle, a linguistics monograph or article represents, ideally

speaking, a piece of reasoning - with documentation at the linguist’s discretion,

depending of what approach the author/researcher has chosen, what school (s)he

professes, and always with available publishing space as an upper limit. The

representation of lexicographical material is generally quite different: Neither an

extensive lexicon nor a morphology is something you just publish in the shape of one line

of reasoning. It is a result. How it was obtained is simply a different matter and can be

accounted for elsewhere. To the extent that lexica or morphologies can be formulated in

terms of lists and tables, it will always be possible to represent them as such - either in

print or on the screen - even if the sheer quantity may make it an impossibility in practice.

(Or at least it will make the result unpractical.) This holds for “normal” morphological

overviews and dictionaries intended for common use by ordinary people, i.e. texts and

graphs that can be printed or otherwise published. However, similar publishing is not

possible in the case of virtual morphology and dictionaries, entities that are designed to

be implemented as a part of a program – not just published as is by means of a program.

Or to state it differently: Many digital language resources, including those of a

lexicographical nature, simply cannot be graphically represented in practice, a property

they share with hypertext or any computer program. These resources work – with an

associated program/interpreter. What you actually can publish, are, as already mentioned,

rules and tables etc.

Since the existence of lexicographical material, i.e. all language resources at word

level and “below”, is principally external to any documentation in the way outlined

above, it seems natural to document the production of this type of digital language

resources in more or less the same manner as any other engineering product, a bridge, for

instance: First of all, describing the external circumstances of the production (the

“engineering” part of it) as well as its result: quantities, qualities and models in various

formal formats. Secondly, by discussing relevant problems encountered and solved

during the creation process.

Personally,8 I have tried to document the lexicographical projects I was involved in at

IBM Norway in the 1980s the engineering way, so to say: Engh 1991a, Engh 1992a,

Engh 1992b, but especially Engh 1991b and Engh 1994, Engh 2009 and Engh 2011.

These can be summarised as external descriptions of the respective objectives, of how

and when the project work was carried out, with information about the raw materials,

about the point of departure or base and, finally, they contain an account of the resulting

quantities. Internal aspects, such as linguistic analyses and assessments are only

mentioned superficially and as specimens in order to give a flavour of the work involved

- always within the limits of what could be made known without disclosing corporate

secrets.

The trustworthiness of this type of documentation can be assessed by the exactness of

the description of the process, by the lack of descriptive incoherence, by the truth of

every controllable fact mentioned, including the chronology, and by the reasonable

relationship between the effort invested and the actual result. In addition to references to

8

One may ask whether one can be justified to write one’s own history. Again, this is the engineering way:

Engineers mostly document their own activities and the products that result from it. Anyway, for a linguist

it should not be that shocking after all, since both linguists and computational linguists always report their

own findings and thoughts themselves.

5

the linguists who were involved. It certainly is documentation, but does it actually work

as documentation?

Unfortunately, there are signs today, more than twenty years after the discontinuation

of the Norwegian IBM project, that such an approach is not sufficient. The project is

hardly ever mentioned in the relevant literature9 and even allegations of fraud have been

levelled against it. Now, you can always point at a bridge. It is there, or at least you can

see a picture of it. Digital language resources are less tangible, and may even have

disappeared from the public eye in their original form,10 which is more or less the case of

the Norwegian digital language resources created by IBM in the 1980s. But it is still

there, although integrated in a different context.

In what follows, I am going to give an abstract of how the lexicographical language

resources were effectively created at IBM Norway in the 1980s. In order to refute

allegations about their origin and their very nature based on what is – to adopt a

benevolent interpretation – a selective misinterpretation of earlier documentation

attempts.

2 The project

The low academic status of lexical and morphological resources creation is in strong

opposition to its importance and to the quality required. In fact, high quality is a

prerequisite for anything else than computational linguistic toy systems. Now, toy

systems usually have no practical value – and are of no interest in a business context. So,

at a time when most computational linguistic research was concerned with small systems

working for a small subset of words only,11 it was only natural for IBM to advance on a

broad front when the company decided to create language sensitive software: In a first

phase, a list of all possible word forms of the written language was to be compiled, then

an adequate, extensive, and correct12 lexicon and a corresponding morphology, further a

synonyms dictionary as well as additionally “enriched” dictionaries. Later, these

resources constituted the basis for grammar development (intended for writing support

and style critiquing systems to start with) and, in the end, a system for machine

translation. (See Engh 1992c ) Many other types of applications were planned, but never

realised. The intention was to create linguistic “engines” for many kinds of user programs

that, eventually, would be put to the market for practical use. Thus, the question of

intellectual property was important already at the outset – with all the significance that

American companies attach to it. And it was all shrouded in corporate secrecy.13

9

IBM linguistic projects and their results have been largely ignored in Academia. For instance, neither

IBM’s Norwegian project nor the corresponding projects for the other Scandinavian languages were even

mentioned in the survey section about digital processing of the Scandinavian languages in the relevant

volume of the reference series Handbücher der Sprache und Kommunikationswissenschaft (Allén 2002).

One reason may be, though, that the Norwegian project was the only one to have lasting effects for the

local linguistics community.

10

Although copies of the orginal files may be kept on tapes, of course – as long as they last.

11

With poor prospects of working in a real-life, scaled-up version.

12

From a normative point of view, in this case.

13

Only the project leader and his management at IBM had a general view of all the details and knew what

was the objective of the development work at each stage. The linguists participating in the sub-projects

only knew what they needed to know in order to perform their respective tasks. The very existence of the

projects was only made public after the announcement of the software products of which they were a part.

6

2.1 Initial stage – the base dictionary

The project was initiated in 1984, when IBM launched a corporate offensive to create

language sensitive software in parallel for all the major written languages of Europe.

Since IBM Norway had no staff with the necessary linguistic competence at the time, it

turned to the University of Oslo for assistance. A joint project was organised with the

specific aim of developing necessary Norwegian language resources. The author of the

present article was contracted as leader of the project.14

The official start of the project was 1 July 1984. After necessary education and a

workshop session at IBM facilities in Gaithersburg (Maryland), the practical work started

in late August 1984. To supervise the project, a joint steering committee was appointed,

consisting of Even Hovdhaugen (professor of general linguistics, dean of the faculty of

arts and humanities) Jo Terje Ydstie (lecturer, applied linguistics), and Jan Hølen

(advisory systems engineer, IBM Norway) in addition to the project leader. The

committee had one meeting, where the project leader’s implementation plans and

linguistic guidelines were approved. After 15 February 1985, no formal ties existed

between IBM Norway and the University of Oslo. However, Jan Engh continued as the

project leader, now as a regular IBM employee, keeping informal contact with the

university and in particular with Dag Gundersen (professor of Norwegian lexicography).

The project took place on IBM premises and it was 100% funded by IBM, which also had

the exclusive right to the research and development results. The entire project was carried

out on IBM mainframes.15

A brief sketch of the technology involved and of the technicalities relating to the

progress of the project has been given most recently in Engh 2009. Here, I shall give an

account of the practical aspects of the linguistic development. The linguists taking part in

IBM Norway’s lexicographical activities in addition to the group leader are all mentioned

in the appendix, with indications of their particular role in the respective sub-projects.

The objective of the initial phase of the project was to cater for the Bokmål variety of

Norwegian, according to the official standard laid down by Norsk språkråd.16 From the

beginning, all possible lexical variants were included, even “permitted non-standard”

word forms (“valgfrie former”). In the last version, however, only the regular, optional

forms of the official “textbook standard” (“læreboknormalen”) were included.17 The

development of Norwegian Nynorsk resources did not start until 1988.18 Thus, it is

natural to focus on the Bokmål development, and to mention just a few critical facts

about the Nynorsk part of the project, since, in principle, the same kind of problems were

encountered during the development of resources for both standards of Norwegian.

Furthermore, the existence of the Bokmål project is the one that has been most seriously

contested afterwards.

14

As senior scientific officer, “førsteamanuensis”, and university employee, “oppdragsforsker”.

Under VM on System/370.

16

The ‘Norwegian language council’, the standardisation authority for the Norwegian language. Since 2005

known as Språkrådet.

17

This reduced the size of the implemented lexicographic products (see below), but had an insignificant

effect on their coverage in actual texts.

18

Vikør 2001 describes the relationship between Bokmål and Nynorsk.

15

7

The practical goal of the very first part of the project was, basically, to create one

extensive list of correct word forms. In a next step, the word forms documented were to

be sorted and classified according to a set of technical specifications. Several sub-lists

based on frequencies and numerous smaller word lists were to be developed in order to

satisfy specific system needs.

By far, most resources were spent creating the main list of word forms, the “base

dictionary”. There were two main requirements: Firstly, the coverage was to be

extensive, catering for the Norwegian vocabulary in general. Secondly, it should contain

unique forms only. The former requirement implied that the kernel vocabulary of the

language was to be covered, adding as many other words as possible – without an eye to

technical terms (computer terms, business terms etc.). Furthermore, all correct forms of

all lemmas should be entered. The latter requirement meant that the list had to contain no

duplicates/homographs and that this had to be prevented already in the input files, cf. p.

11. As a consequence, the result was not lemmatised, and did not satisfy the criteria of a

morphology, linguistically speaking. This made it practically useless for any other

purpose than the one it had been designed for. Thus, there would have been no reason to

attach importance to this part of the project from a purely linguistics point of view, if it

had not been for the question of lemma selection. This is an important aspect, though,

since the Bokmål base dictionary later served as the foundation for the development of a

lexicon and a morphology for Bokmål. So, the challenges of lemma selection will be

discussed in connection with the base dictionary for practical reasons, leaving the

question of how the word forms of each lexeme were processed to the subsequent lexicon

and morphology chapter.

2.1.1 A pioneering task …

The linguistic compilation of the base dictionary turned out to be a far greater task than

the computationally oriented American management had thought in advance. This was

mainly due to two sets of factors. First of all, one extra-linguistic factor: The general lack

of available Norwegian on-line dictionary data. IBM could not rely on electronic

language resources created by other private companies or by public research institutions.

In the second place, three linguistic factors: Firstly, the current state of the

standardisation of Norwegian. Characterised by a high and complicated degree of

variability, it was, and in fact still is, principally different from the standardisation of

other European languages. Unfortunately, its standardisation was also found to be much

more incoherent than expected. Secondly, the number of homographs of the Norwegian

base vocabulary. Finally, as a third complicating factor: The problems encountered while

trying to apply the rather simplistic IBM design of word compounding tagging to

Norwegian word forms. In fact, these linguistic factors alone were sufficient to explain

why the project took nearly one year to accomplish. In the present context, however, the

lack of digital language resources is what merits a more thorough account, given its

consequences for the entire project.

In 1984, there was no language resource centre providing lexicon, morphologies etc.

in addition to dictionaries and texts for Norwegian.19 Furthermore, of the scarce and

sparse digital resources that existed at that time, hardly anything was available for

19

Excepting the embryonic Norsk tekstarkiv, with a comparatively small number of texts. See below.

8

commercial use. So, a natural point to start would have been the processing of running

texts. There were many rocks in the sea, however. In the mid-1980s, it was still

unrealistic on technical grounds to establish extensive electronic text archives or corpora

like those we take for granted today. Creation of corpora was difficult, even when

computer storage was available, since computer composition was not common. Instead,

printed texts had to be converted, a rather expensive operation. Either the texts had to be

entered manually or by means of primitive optical character recognition, which required

extensive proofreading. Conversion would also have been generally illegal: All the major

Norwegian publishing houses at that time were strictly opposed to any sale of the right to

their texts – even for non-commercial, internal use only.

For IBM Norway, the solution was to use internal texts of any kind as the point of

departure in addition to the corporation’s own wordlist, NORFRQ LIST. Native language

user linguists supplemented this material to the best of their linguistic competence,

adding new words while consulting printed dictionaries when necessary - by looking up

single words, one by one.

2.1.2 Selection and entering of words

At the outset, the selection of entry words was based on NORFRQ LIST. This was a

frequency list of obscure corporate origin, probably compiled at IBM’s Austin (Texas)

laboratory in the beginning of the 1980s as input for the spelling checker of IBM’s

dedicated text processor, marketed in Norway as Serie 80. The list contained 50.000

unique word forms and was apparently based on a relatively big sample of technical texts

and business correspondence to and from IBM Norway. Its content, however, was of a

rather heterogeneous nature and it had obviously not been subjected to any screening by a

linguist: Quite a number of the words were misspelled, there was a great number of nonstandard (obsolete) and utterly infrequent word forms. E.g. “syv”, “tyve”, “hverken” 20

and “asbesthanskeprodusentenes”,21 and, surprisingly, quite a few words pertaining to

Norwegian Nynorsk. Despite a certain imbalance as far as technical terms and business

terminology were concerned, NORFRQ LIST did contain a high number of word forms

belonging to what one would usually count as the kernel vocabulary. However, quite a

few important words were missing, the most prominent being “rød”, ‘red’…

So, it was clear already from the beginning of the project that NORFRQ LIST was

insufficient as a base. Consequently, the selection of words for the base dictionary was

extended to the few electronic texts available to the project – mainly of corporate internal

origin - in addition to extensive excerption/registration. All electronic internal

communication, e.g. business announcements, instructions and directives, social

information etc. was processed in the quest for additional words, and the project members

regularly scanned their own correspondence. As soon as practically possible, the staff

made diligent use of IBM’s spelling checker for the 370 mainframe environment,

PROOF, in order to detect unrecognised words.

Meanwhile, a systematic registration of lexical fields was carried out: E.g. parts of the

body, colours, names of most chemical elements, car parts, furniture, measures,

construction terms, fishing equipment, maritime terminology, sports, sports gear and

20

21

Instead of “sju” ‘seven’, “tjue” ‘twenty’, and “verken” ‘neither’ of the official Bokmål standard.

‘of the producers of asbestos gloves’.

9

other fields of a concrete nature in addition to more elusive lexical fields such as

thought/meaning/opinion, truth and falsity, love/likes and hate/dislikes etc.

Once the kernel vocabulary was considered to be properly covered, the project staff

simply endeavoured to include as many other correct word forms as possible, by casual

excerption after the lexicographer’s discretion.

As the base dictionary was supposed to contain frequent names, the more common

given names and surnames were entered, in addition to the names of the 100 biggest

private companies in Norway, a selection of geographical names in Norway and abroad, a

list of post offices (including neighbourhood names), and the complete list of Norwegian

townships. The sources were:

Stemshaug, Ola et al.: Norsk personnamnleksikon. Samlaget, Oslo 1982

Utvalg av slektsnavn som hører til de mer vanlige. Justis- og politidepartementet, Oslo 1983

Norges største bedrifter. Oslo 1984

Cappelens skoleatlas. Verdensatlas for grunnskolen. Oslo 1984

Postadressebok. Postdirektoratet, Oslo 1984

Standard for kommuneklassifisering. Statistisk sentralbyrå, Oslo 1985

The entire word list was finally supplemented with available frequency data: Remaining

words were entered, and the frequency information of NORFRQ LIST served as a point

of departure for the compilation of various frequency components. During this process,

Heggstad, Kolbjørn: Norsk frekvensordbok. De 10000 vanligste ord fra norske aviser.

Universitetsforlaget: Bergen 1982

was consulted as a supplement.22

For a later version of the base dictionary, IBM Norway was able to purchase a

handful of texts in machine-readable format: A small collection of texts from Norsk

tekstarkiv and a collection of laws and law related texts from Lovdata. These texts were

simply converted to word lists, duplicates were eliminated, and the result compared with

the working copy of the base dictionary at its current phase. Similarly the base dictionary

was checked against

Hanssen, Eskil A.: “Ordforrådet i et talespråksmateriale”. In Hanssen, Eskil A., Ernst Håkon Jahr,

Olaug Rekdal, and Geirr Wiggen (eds.): Artikler 1-4. Talemålsundersøkelsen i Oslo (TAUS),

Oslo 1986

Word forms were identified with respect to their lexeme; the lexeme was expanded to

all conceivable forms,23 which were finally entered manually: Every entry word and its

inflected forms were typed in one by one by the lexicographers along with the required

information about part of speech and combinability.24 Also, the constituents of all

compound words found were properly identified and entered with all possible inflected

22

The usefulness of Heggstad 1982 was clearly limited. The data were evidently based on a rather small

corpus, and a biased one as well: The prominence of such words as “Saigon” confirmed its newspaper

origin from an intense phase of the war in Viet Nam.

23

Including genitiv (with the -S suffix) of every forms of nouns, adjectives and past participles of transitive

verbs.

24

I.e. their ability to occur as constituent in a compound word – in front, in the middle, at the end, or

anywhere etc. See Engh 2009, p. 263.

10

forms in the base dictionary as separate entries in addition to all imaginable combinations

in the form of (other) compounds. This even included all variants of the words involved.

Thus, in addition to VANN ‘water’, LØSELIG ‘soluble’, and VANNLØSELIG ‘soluble

in water’, VATN ‘water’ and LØYSELIG ‘soluble’ were entered, and so were

VANNLØYSELIG, VASSLØSELIG, and VASSLØYSELIG25 all meaning ‘soluble in

water’.

Finally, every word form of the base dictionary was provided with marks indicating

all correct hyphenation breakpoints.

2.1.3 First version ready

The first version of the base dictionary was completed 21 June 1985. 26 Technically

speaking, it consisted of two main files, a stems file and an endings file, in addition to a

number of minor files with a more technical content. Together, they provided input for

the “building” of a component that in its compacted form would drive a spelling checker

and a function for automatic hyphenation.

The base dictionary contained 292,190 unique word forms, which secured a fairly

high coverage of word forms in running Bokmål texts.27 Moreover, the number of

lemmas covered was comparatively higher than one would expect from this figure,

although the precise coverage was unknown, due to the way the requirement of unique

word forms were to be implemented. For instance “for” as forms of the noun FOR n

(‘lining’; ‘fodder’), the verbs FORE (‘line’; ‘feed’) and FARE (‘go, travel’), and the

adverb, conjunction, and preposition FOR (‘for’; ‘because’; ‘for’) were all counted as one

entry. No matter the different meanings and the different parts of speech.28 Consequently,

it is impossible to know how many lexemes that were actually covered. I.e. how many

lexemes that were fully covered intentionally – and how many lexemes that were fully or

partially covered unintentionally.

In this connection, it is also important to stress that the stems and endings of the input

files were “technical” stems and endings, not linguistic ones. The endings could be

regular inflectional or derivational suffixes or clusters of both. One example relating to

“for” mentioned above: On the basis of “for” as a stem, one could generate not only

“fore” (infinitive of FORE), but also “foret”, “forene” (definite form singular and definite

form plural of FOR) etc., but even “forets” (definite form singular plus genitive), “forer”

and “foreren” (indefinite form singular and definite form singular of FORER ‘feeder,

supplier’), “foring” and “foringas” (indefinite form singular and definite form singular

plus genitive of FORING f ‘ling’; ‘feeding’).

The motivation for the non-lemmatised base dictionary was computational efficiency:

Compaction and minimisation of the number of operations – and the time needed - to

verify a given character sequence as a valid Norwegian word according to the current

25

“vass-” is the proper form of VATN as an initial constituent of a binary compound.

A second, extended version was ready for implementation 14. December 1985.

27

In fact, much higher than what was usual for spelling checkers at that time. According to Fjeldvig and

Golden 1989:126, for instance, the spelling checker of WordPerfect was based on a list of 60 000 unique

word forms only.

28

In this particular case, the part of speech was indicated as the set “ANRV”. A ‘adverb’, N ‘noun’, R

‘preposition’, and V ‘verb’.

26

11

standard. The whole point of the technology adapted was fast pattern matching with

documented valid words.

The base dictionary was certainly not a morphology. However, it turned out to be

very important later on as the foundation of IBM’s morphology for Norwegian Bokmål.

But at the time of the base dictionary development, neither IBM Norway’s natural

language development group nor local management had any knowledge of future

corporate plans for a morphology.29

2.2 Morphology

Lemmatisation became a requirement only in the third update of the base dictionary,

when a synonyms dictionary was implemented. A morphology was necessary as a

“bridge” between the word forms identified by the base dictionary and the lemma forms

of the synonyms dictionary entries. (The synonyms dictionary contained no inflected

forms.) So, the third version of IBM’s lexicographical component for Norwegian Bokmål

was to contain a morphology.

In 1986, there was no digital morphology for any variety of Norwegian that could be

purchased off the shelf. In fact, there was none at all that would satisfy IBM’s

requirement for broad coverage. There was even little other material available in general

to build a digital morphology on. During the last 50 years, morphology had been a

neglected part of Norwegian linguistics, in the sense that focus had been on limited

subsystems only. No adequate account had been given of the totality of Norwegian

morphology. Also, morphological information of printed dictionaries was inadequate and

not extensive. So, an entirely new lexicon and morphology had to be developed by IBM

Norway. (See Engh 1991b, 57)

The basic linguistic part of the morphology development was carried out by the

project leader, who also took part in the development and adaptation of the morphology

software in cooperation with Beverly Knystautas (of IBM’s Gaithersburg laboratory).30

The work started in 1986.

When delivered in the winter of 1986-87, the first version of IBM’s morphology

consisted of two files, one inflections input file and one lexicon input file. They

comprised 550 different paradigms, mapping to 46.220 lexemes.31

29

This was the reason why no statistics about lexeme coverage were gathered during the compilation

process.

30

Assisted by Carmen Valladares of Centro Científico de IBM (Madrid), among others.

31

Additionally, the total quantity of words had increased compared to the earlier versions of the IBM’s

Norwegian Bokmål lexicographic project: On the basis of the expanded lexicon and morphology, 418,922

unique word forms could be generated, which were all covered by the updated base dictionary.

12

2.2.1 The format

Was IBM’s morphology a morphology in the habitual meaning of the word? Yes and no.

It was a morphology in the sense that it gave an explicit account of every word form of

every lemma. It differed from a customary linguistic morphology in two respects:

Complex endings and one special requirement as far as the lemma was concerned. The

endings could be more than suffixes of the normal linguistic kind, as they included both

suffixes and sequences of suffixes plus yet another suffix. For instance an inflectional

suffix, e, en or ede, plus a medio-passive S-suffix or an S genitive suffix, es (as in

“kastes” ‘is thrown’), ens (as in “mannens” the man’s’) edes (as in “forkastedes” ‘of [that

which is] thrown’) were all counted as one ending respectively. As for the lemma, it

could only belong to one paradigm: One lemma could not be inflected according to two

or more paradigms and there were no “exceptions”: no secondary or tertiary rules. In a

way, the morphology format could be thought of as “flat” or “two-dimensional”.

On the one hand, the verb SPREDE ‘spread’, for instance, would be conjugated

according to a paradigm whose past slot had two options, -de and –te, producing

“spredde” and “spredte”, not as belonging to the same paradigm as either KREVE

“krevde” or NEVNE “nevnte”, with just one optional past form. In traditional

morphology, this would have been an option. On the other hand, a verb like KVINE

‘shriek’ belonged to a paradigm with the following past options: {apophony I>EI + 0

ending} and -te, producing “kvein” and “kvinte”. According to traditional morphology,

KVINE would be conjugated according to one of two separate paradigms, either as

KLIPE ‘pinch’ (apophony I>EI) or as FORELESE (past form “foreleste”). Of course, this

linkage between the lemmas and their respective unique paradigms was not only confined

to verbs. For instance, nouns that can be inflected as masculine, feminine and/or neuter

were, in principle, handled in the same manner. To mention a few examples: SKJELL

‘shell’ fn32, SNØRR ‘snot’ fn, FLO ‘flow tide’ fn; NYRE ‘kidney’ fmn, HENGSEL

‘hinge’ fmn, GARDIN ‘curtain’ fmn; KRANGEL ‘quarrel’ mn, FJØS ‘cowshed’ mn,

HENSEENDE ‘respect’ mn. All were attached to one, individual paradigm.

There was one more important consequence of the IBM morphology format’s lack of

secondary rules etc.: “Local” adaptive rules that would adjust the stem to a typical ending

when needed were equally out of question. For instance, STOL ‘chair’ and

KONFERANSE ‘conference’ are said to belong to the very same paradigm by traditional

morphology, cf. “m1” of Bokmålsordboka (Landrø, Wangensteen et al. 1986). However,

the final E of KONFERANSE has to be reduced before attaching the –EN definite article,

in contrast to nouns such as KNE ‘knee’, “kneet”, and HÅNDKLE ‘towel’, “håndkleet”,

where the definite singular neuter -ET suffix is added to the stem with an E final. Other

types of stem adaptations in the case of nouns are doubling of final single consonant,

KAM ‘comb’ plural indefinite “kammer”, elision of unaccented vowel in the last syllable,

REGEL ‘rule’ plural indefinite “regler”, and elision of unaccented vowel in the last

syllable and reduction of stem consonant, TITTEL ‘title’ plural indefinite “titler”.

In all these cases, a special paradigm was defined to cater for these and other lemmas

sharing the same characteristics. This was of course also the case with lemmas displaying

32

“f” for ‘feminine’ because the only definite article beside a possible neuter one is the suffix –a. While

most nouns of Bokmål usually considered to be feminine may equally have the –en suffix, which is

typically masculine, -a is unambiguously feminine.

13

stem alterations such as STRYKE ‘stroke, pat etc.’ and SKYVE ‘push’, which are

traditionally considered to belong to the same conjugation. Yet, they differ with respect

to the J that has to be inserted before an Ø after a SK-cluster (pronounced ʃ): STRYKE “strauk”/“strøk”, SKYVE - “skauv”/“skjøv”. In the IBM morphology, STRYKE and

SKYVE were attributed to two different paradigms.

Not only did one lemma belong to one paradigm only; complementarily, what one

would customarily need one single paradigm to describe in a mainstream linguistic

morphology, would be accounted for by means of two or more in the IBM format. Why?

Although IBM’s morphology was a morphology in the true, linguistic sense of the word,

it was organised according to special computational requirements. This was a technical

necessity because of the systems architecture for which it was intended. It would have

been perfectly possible from an isolated computational point of view to implement a

morphology in a more traditional linguistic format, with rules applying to rules etc.33

However, the very basic technical requirements were not a subject of discussion, and the

Norwegian natural language processing group simply had to satisfy them. Yet, the IBM

morphology was an adequate, extensive, and correct morphology for Norwegian Bokmål.

And it was the first of its kind – not only technically speaking, but also in so far as it gave

a complete description of the linguistic facts on a strictly synchronic basis. The result

could easily be transformed into a linguistic morphology of a conventional format.

Moreover, the creation of the complete morphology on the basis of discontinuous and

often inconsistent morphological information from printed sources, among other things,

was far from trivial.

2.2.2 The linguistic development process

As already mentioned, the linguistic part of the development was carried out by the

project leader alone, mainly on the basis of his language competence as a linguist and his

experience from the base dictionary. First, a draft version was developed that catered for

as many different paradigms as possible. Later, the morphology was constantly revised in

confrontation with the words of the base dictionary.

One by one, the words of the base dictionary were categorised and the morphology

adjusted as required and more paradigms and even categories were added until the entire

base dictionary had been processed - and the morphology had reached a stable state. Then

the lemmas of the lexicon were expanded by means of the morphology in order to

produce all word forms. The result was printed out, and the printouts were proofread.

Whenever an irregularity was detected, the lexicon and/or the morphology were corrected

accordingly, and, eventually, the proof reading process repeated.34

Basically, the morphology development consisted in registration, and in certain

respects, the entire process represented a reverse of the original base dictionary creation

process: Every word form generated by the base dictionary was attributed to its lemma or

33

It would not have been possible to assign such rules automatically, though. Cf. the case of last syllable

vowel elision, where any clear principle seems to be missing, at least from a synchronic perspective. E.g.

“ankeret” and “begeret”, definite singular forms of ANKER ‘anchor’ and BEGER ‘cup’, respectively – in

contrast to “alteret” or “altret” and “mønsteret” or “mønstret” of ALTER ‘altar’ and MØNSTER ‘pattern’.

34

After the morphology had reached a stable state, its maintenance and expansion were gradually taken

over by Jørn-Otto Akø. As for the other linguists involved, see the appendix.

14

to all possible lemmas (like in the case of FOR35), and all lemmas were subsequently

attributed to their respective correct paradigms. This implied that the last operations

performed during the creation of the base dictionary, singling out the correct word forms

etc., had to be repeated in principle, since no records had been kept. Cf. p. 12

The following written sources were consulted:

Sverdrup, Jakob, Marius Sandvei and Bernt Fossestøl: 1983, Tanums store rettskrivningsordbok.

Bokmål. 6 edition. Oslo: Tanum-Norli

Landrø, Marit Ingebjørg, Boye Wangensteen et al.: 1986, Bokmålsordboka. Bergen:

Universitetsforlaget

Norsk språkråd: 1972-, Årsmelding. [Annual reports from The Norwegian Language Council] Oslo:

Norsk språkråd

Here “consulted” means that the printed dictionaries were used the way their authors and

publishers had intended: Words were looked up in order to verify the linguist’s

competence when necessary.36 In this connection, it is important to know that Tanums

store rettskrivningsordbok and Bokmålsordboka had - and in fact still have - a semiofficial status as the documentation of the official norm, as defined by Norsk språkråd. In

fact, there was hardly any other place where the norm was systematically documented,

however, not without numerous defects.

The linguistic challenge of this phase of the process was related to completion. The

special technical format forced the linguists to control whether the traditional paradigms

fitted the inflected forms of the class of lexemes they were supposed to before they were

implemented. It also imposed a raised awareness of peripheral forms of the respective

paradigms. As a result, the linguists had to draw the consequences of the current official

standardisation of Norwegian Bokmål to an extent not represented in any printed source.

By doing so, every inconsistency was cleared up and every error encountered corrected,

in addition to the detection and chartering of non-standardised parts of the lexicon.

In practice, this task implied that the linguists had to infer how each word ought to be

inflected, one word after the other, and to systematise the result in relationship to

traditional paradigms – as well as to adapt the result to all possible words requiring not

yet recognised exceptions and additional rules. This was far from a trivial task, given the

often confusing information of the relevant dictionaries.

A few typical cases of such vagueness: What was the correct form of the verbal noun

corresponding to verbs with a “floating” J: SVELGJE ‘swallow’ and SVELGING f

‘swallowing’ with J elision in contrast to BØLGJE, ‘wave, roll’ and BØLGJING f

‘waving, rolling’, i.e. without J elision. Should the present participles of the short and

long versions of what is historically and functionally the same verb, e.g. BE/BEDE ‘ask;

beg’, SKA/SKADE ‘damage; hurt’, KLE/KLEDE ‘dress’, AVKLE (but not

*AVKLEDE) ‘strip; lay bare’ etc. contain a stem final consonant or not: “beende” and/or

“bedende”, “skaende” and/or “skadende”, “kleende” and/or “kledende”, “avkleende”

and/or “avkledende” respectively. These and numerous other such cases simply had to be

handled one by one.

Moreover, awareness of peripheral forms even has another aspect, not necessarily

linked to normative linguistics. Two prominent instances are plural of nouns and

35

36

See p. 12.

Cf. p. 3.

15

comparison of adjectives. Separate paradigms were created for nouns without a plural,

e.g. FEBER ‘fever’, MAT ‘food’, LYKKE ‘happiness’, and GODFOT ‘[idiomatically]

healthy foot’, for nouns with no singular, e.g. INNVOLL ‘intestines’, BOMPENGER

‘toll’, HVETEBRØDSDAGER ‘honeymoon’, and for adjectives without a comparison,

e.g. ABSOLUTT ‘absolute’, KJEMPEFLOTT ‘excellent’, GLITRENDE ‘brilliant’,

GRØNNFARGET ‘(dyed) green’.37

The completion process was carried out in close cooperation with Norsk språkråd. In

quite a number of cases, its Bokmål section manager, Arnljot Thoresen and its

lexicographers were consulted directly.38 Norsk språkråd later received a list of errors

and unclear information in Tanums rettskrivningsordbok detected during this process,

which at least potentially represented regular morphological research.

The distance between traditional morphology and the result of the standardisation and

the completion carried out to its ultimate consequences under the IBM morphology

project can be measured by the number of conjugations. Norwegian Bokmål is usually

said to comprise 10 conjugations39 (cf. for instance Berulfsen 1967, 141ff.) while, in

practice, the verbs could be categorised in no less than 243 distinct classes according to

the IBM’s conception of digital morphology. (See Engh 1996.) In addition to the partly

defective standardisation and the inaccuracies of traditional morphologies and to the fact

that the morphology was conceived without a view to diachrony, this disproportionate

relationship between the numbers of conjugations was to a great extent due to the internal

variation characterising Norwegian. In the case of languages with a regular spelling and

regular inflections, and, above all, no internal variation, conversion and registration may

be a trivial task as far as linguistics is concerned. At least in theory, neither corrections

nor completion etc. will be needed.

Symptomatically, a similar effort was apparently not needed in order to implement a

morphology for any other language that was part of IBM’s project for the creation of

lexicographical language resources.

2.2.3 The last version of the Bokmål morphology

When the last official version of the lexicon and corresponding morphology was finished,

it comprised 705 paradigms mapping to 65,128 lexemes. In a pre-release to a next

version, which was never implemented in any software product, the number of lexemes

had risen to 121,577. This sharp increase was due to the fact that “new” words from one

year of the major newspaper Aftenposten were added and classified.40 On the basis of this

material, it was possible to generate more than 1.1 million unique word forms.

37

The soundness of such a classification and its relativity in relationship to application software where it

may be implemented etc. are discussed in Engh 1993.

38

Especially by telephone in what probably can be described as an unprecedented series of intense

consultations for the institution.

39

4 regular and 6 irregular conjugations. Of course, exclusive of their exceptions, of optionality etc.

40

Including an extensive number of proper names.

16

2.3 Other lexicographic products

As mentioned earlier, the lexicographical activities of IBM Norway’s natural language

processing group were more comprehensive than just the lexicon and the morphology for

Bokmål.

The corresponding Nynorsk project has only been mentioned in passing. In principle,

however, it was developed along the same lines as its Bokmål analogue - with the notable

exception that the linguists were able to develop it in a “natural” sequence, first lexicon

and morphology and then the “base dictionary”. This brought about a considerable

improvement in production efficiency. The linguistic problems encountered during this

process were similar to those of the Bokmål process, though.

As a point of departure, the existing Bokmål files were simply “translated” into

Nynorsk41 Then the result was completed, following the same routines as in the case of

Bokmål. However, only the regular, optional forms of the official “textbook standard”

were included and no genitives with the -S suffix, except for proper names.42 This

implied that the Nynorsk paradigms were constituted by fewer categories, and that the

total number of word forms generated was relatively lower compared to its Bokmål

counterpart, without imperilling the coverage.

The development started 4 January 1988, and the first version was shipped to the

IBM laboratory at the end of January 1989. In the second and last delivery of 12 June

1990, however, the lexicon had been expanded to 110,412 entries while the number of

paradigms was 576.

Further, synonyms dictionaries were compiled for both Bokmål and for Nynorsk.43

The former consisted of 17,337 separate entries when its second and last version was

included in relevant application software. The latter contained more than 25,000 entries

in its only version. As a by-product of the compilation process, “new" words were added

to the corresponding lexicon and morphology.

A number of other lexicographical products were prepared, as well. Of special

interest in the present context is the enrichment of the Bokmål vocabulary in terms of

information about semantic and syntactic properties (cf. p. 3). All lemmas were classified

with respect to 180 characteristics (Engh 1994, 111ff.). One sample of syntactic

information44 added to adverbs: systematic information about positional properties.

41

I.e. corresponding stems were listed together with different stems with the same meaning as stems in the

Bokmål list, and every lemma form was attributed to a particular paradigm etc.

42

In accordance with the mainstream interpretation of the Nynorsk norm.

43

The existing printed synonyms dictionaries were not ideal for IBM’s primary purpose: to assist users

improving their Norwegian, probably not for implementation in any search program either. They were

more or less designed for solving crossword puzzles (Gundersen 1984) or for helping Bokmål users to

write Nynorsk (Rommetveit 1986).

44

Based on characteristics attributed according to a Poul Diderichsen style sentence model or position

grammar (Diderichsen 1946), which turned out to be very useful when the Norwegian PLNLP grammar –

the first broad coverage analytic grammar for Norwegian Bokmål - was developed (Engh 1994).

17

BAREPART - can only appear as an ADVP when functioning as a verbal particle

FRIADV - light adverb that may appear in the beginning of an NP or an ADVP

IKKEADVPS - cannot form an ADVP alone

FMADV - may only appear as the nucleus of the grounding field or the nexus field

FSADV - may only appear as the nucleus of the grounding field or the content field

MADV - may only appear as the nucleus of the nexus field

FADV - may only appear as the nucleus of the grounding field

SMADV - may only appear as the nucleus of the content field

MSADV - may only appear as the nucleus of the the nexus or the content field

IKKEPRMJ - cannot modify an ADJP as a premodifier

IKKEPRMA - cannot modify an ADVP as a premodifier

Examples of other types of syntactic properties, general semantic properties and

information about style level and special lexical status:

V0 - zero valency

V2E - bivalent verb with two obligatory arguments

OBJINF - verb with possible object infinitive

A0 - may occur as finite verb of a complex passive phrase

KOLLEK - collective term

MASSE - mass term

TELLELIG countable term

FRANSK - French loanword with authentic orthography

FYSJOM – “indecent” word

Still, the Bokmål lexicon and morphology constituted the most important part of the

IBM Norway lexicography project, since it was a first, since it was the most

comprehensive part of the project - but also because it became disputed.

2.4 Bokmålsordboka - a digression

By the end of 1989, more than five years after the start of IBM Norway’s natural

languages processing project, its lexicographical resources for Norwegian Bokmål had

reached a stable phase. The corporate attention was now focused on the next linguistic

modules that were to be developed. The first priority as far as Bokmål was concerned was

to develop a grammar that would be implemented in a system for writing support and

style critique. More applications were planned for, and IBM Norway was asked to

procure digital material that could be relevant one way or the other in this connection.

The idea was to arrange for internal use only rights in the first place, in order to take a

closer look at the format and, if needed, test it in the original or a modified format in an

IBM development environment. Once its appropriateness had been established and, most

importantly, once the concrete need for its implementation arose, IBM Norway would

engage in negotiations for a licence for commercial use. Unfortunately, IBM Norway

abandoned natural language processing development and the development group was

dissolved before such a stage of development was reached.

Despite overt misgivings from major publishers, the project succeeded in acquiring

the current digital versions of the following titles:

18

Bjarne Berulfsen and Torkjell K. Berulfsen: 1989, Engelsk-norsk blå ordbok. (Kunnskapsforlagets blå

ordbøker) 5. edition. Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget

Kirkeby, Willy A. and H. Scavenius: 1989, Norsk-engelsk ordbok. (Kunnskapsforlagets blå ordbøker)

5. edition. Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget

Berulfsen, Bjarne and Dag Gundersen: 1986, Fremmedordbok. (Kunnskapsforlagets blå ordbøker) 15.

edition. Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget

Rommetveit, Magne: 1986, På godt norsk. Synonymordbok med omsetjingar frå bokmål til nynorsk. 2

edition. Oslo: NKS-forlaget

Landrø, Marit Ingebjørg, Boye Wangensteen et al.: 1986, Bokmålsordboka. Bergen:

Universitetsforlaget

These titles were later made available for IBM internal use only as electronic dictionaries.

This meant that IBM employees45 at the Norwegian headquarter could look up entry

words on their terminals and PCs.

The case of Bokmålsordboka deserves a closer comment. IBM Norway acquired the

right to internal use of Bokmålsordboka for a five years period for NOK 100,000 plus a

yearly fee of NOK 10,000.46 In addition to the appropriateness tests, there were even

plans to analyse the entry words and the words in the definitions, including the examples,

in order to find words not yet covered by the base dictionary or the morphology. None of

these plans were ever implemented. Instead, the digital copy of Bokmålsordboka was put

at the disposal for an engineering student of the then Oslo ingeniørhøgskole,47 Jostein

Baustad. He worked as an unpaid trainee at IBM Norway in order to perform the practical

work for his Bsc thesis. Although probably unheard of in Norway at that time, this type

of student internship was common practice in IBM internationally as a contribution to

university education in natural language processing.

By means of IBM software, Baustad converted the content of Bokmålsordboka in

structured text format to two subsequent database formats: DAM (Dictionary Access

Method) and LDB (Lexical DataBase format). The former was a simple format enabling

look-ups in the electronic dictionary, just like in any printed one – one entry at the time –

in WordSmith.48 The latter facilitated every type of (combined) searches in the electronic

dictionary as a true database by means of LQL (Lexical Query Language). 49

So, it is important to stress that, apart from being used as an ordinary electronic

dictionary by IBM Norway employees, the digital copy of Bokmålsordboka was never

made direct use of – neither as a database nor in any other format.

45

Translators, salesmen, engineers etc.

Cf. contract of 22. November 1989. There were also negotiations with Samlaget about a similar contract

concerning Bokmålsordbokas parallel Nynorskordboka. However, the publisher demanded the staggering

amount of NOK 1,000,000 and negotiations were abandoned.

47

‘Oslo college of engineering’.

48

Cf Neff and Byrd 1988.

49

Baustad also converted the four smaller dictionaries mentioned above to DAM format for WordSmith

look-ups by IBM employees.

46

19

2.5 Discontinuation of the project, results, and documentation

Due to the international financial crisis of the late 1980s, IBM’s development division

discontinued all natural language processing projects. As a consequence, no corporate

funding for dictionary work was provided for 199150. On the basis of local funding, the

activities continued at a somewhat reduced pace till the end of 1991. The natural

language processing group was dissolved, and its leader left IBM.

At the time of its termination, IBM Norway’s lexicographical activities had been

documented in several ways. Preliminary results had been presented on one occasion to

linguists of The National Research council’s computing centre (Bergen)51 in the first

move to make the group’s activities known to the public. Later, linguists from the

University of Oslo were invited on several occasions, individually and in groups, to see

the products at IBM premises (Kolbotn). At that time, these products had already been

implemented in various types of IBM software products. (They were never marketed

separately.) The most important event of this kind, though, was the Nordic conference of

lexicography in May 1991. One conference session was located at the IBM Norway

headquarters at Kolbotn, where a broad presentation of IBM Norway’s lexicographical

activities and results was given: The project leader gave a general overview, paying

special attention to problems identified by the natural language processing group (Engh

1992a), Jostein Baustad presented his engineering Bsc thesis (Baustad 1992), and at a

session on university premises, Jørn-Otto Akø spoke about one particular problem of

lexicographical interest related to IBM Norway’s linguistic research and development:

the vagueness of the current Bokmål standard, particularly as codified in Tanums

rettskrivningsordbok and Bokmålsordboka (Akø 1992). (All three papers appear in the

conference proceedings, edited by Ruth Vatvedt Fjeld et al.) Additionally, the project

leader wrote a comprehensive documentation of the entire lexicographical project during

the last months of 1991 (Engh 1991b),52 and one month before the end of the project, he

gave a presentation at the annual national conference for Norwegian linguistics, MONS

(printed in Engh 1992b).

After the conclusion of IBM’s natural language activities for Norwegian, the

lexicography project was mentioned in Engh 1993, and served as the base for Engh

1996.53 Furthermore, it is briefly described at http://folk.uio.no/janengh/IBMnorsk.html.54

Later, IBM’s research division sold the penultimate version of the lexica and the

morphologies to software companies,55 while IBM Norway transferred the most recent

files to Dokumentasjonsprosjektet56 (University of Oslo) for a symbolic sum.57 For

50

The funding of the parallel grammar project had already been halted as off 3. August 1990.

NAVFs EDB-senter i Bergen.

52

This report and one on the parallel grammar development project of IBM Norway (Engh 1994) were later

deposited at the Norwegian National Library.

53

See p. 17.

54

Accessed 27 March 2013, but available since the late 1990s.

55

Inso used the Norwegian lexica for both spell-checking as well as for enhancing search applications.

From Inso, the lexica and morphologies even reached Microsoft, and through Inxight they found their way

to functions in software from Oracle, Microsoft, Yahoo and many others. Finally, Xerox Research Centre

Europe in Grenoble had a research license to this material. (Ian Hersey – originally IBM, later Inso, Inxight

etc. - personal communication.)

56

Literally ‘The documentation project’, a central public institution for converting non-digital cultural

resources to electronic form through the years 1992-1997.

51

20

unknown reasons, Academia never showed any interest in the “enrichment” part of IBM

Norway’s lexicographical products: information about a variety of semantic and syntactic

properties of words, to which one could also add information about word compounding

and hyphenation.58 Of IBM’s two synonyms dictionaries, the one for Nynorsk was never

used by the corporation. Neither the Bokmål nor the Nynorsk synonyms dictionaries were

published in any other way.

In 1996, Kristin Hagen59 of the University of Oslo revised the IBM lexicon and

morphology for both Bokmål and Nynorsk with three objectives: Firstly, to implement

the latest changes in the orthography of Norwegian, correct a very small number of

errors, and to make minor technical alterations. Secondly, to adjust the parts of speech

following the norm of the recently published Norsk referansegrammatikk (Faarlund et al.

1997). Thirdly, to make certain adjustments as far as the extension was concerned: To

remove all genitive forms and to expand both morphologies with all imaginable forms of

each lemma, both morphological variants and orthographical variants in addition to nonstandard forms.60 The result was linked to Bokmålsordboka and Nynorskordboka and

complemented with lemmas from these two dictionaries. This became later on the basis

of Norsk ordbank,61 a service from the University of Oslo, incorporated in the newly

established Norsk språkbank62 under the auspices of Språkrådet.63 Thus IBM Norway’s

lexica and morphologies constitute an important part of the base of today’s electronic

infrastructure for the Norwegian language,64 unfortunately not generally acknowledged as

such.65

57

Relevant information about the linguistic aspects of IBM’s lexica and morphologies, both Bokmål and

Nynorsk, can be found on http://folk.uio.no/janengh/IBMmorf.html. [Accessed 27 March 2013]

58

A curiosity: After the presentation at the national conference for Norwegian linguistics, MONS, in 1991

(cf. Engh 1992b), the next speaker presented a project that was to start at the Technical University of

Trondheim, NorKompLeks. (It was realised later on as a three years project 1996-1998.) Apart from

creating a machine-readable lexicon and a morphology, its objective was to classify Norwegian words with

respect to valency etc. In other words exactly what had already been carried out by IBM’s natural language

processing group (with the exception of information about pronunciation). Cf.

http://www.forskningsradet.no/servlet/Satellite?c=Prosjekt&cid=1193731511032&pagename=Forsknings

radetNorsk/Hovedsidemal&p=1181730334233 [Accessed 27 March 2013]

59

Former temporary IBM employee. See Appendix.

60

For instance, “mjølkene” ‘the milks’ of MJØLK ‘milk’ and “fantastiskere” ‘more fantastic/amazing’ of

FANTASTISK ‘fantastic; amazing’, “permitted non-standard” word forms, and word forms such as “efter”

‘after’ and “gutta” ‘the lads, words that were catered for in a different way, outside the lexicon and the

morphology in the IBM modal of lexicography. Furthermore, common misspellings and abbreviations were

added. [Kristin Hagen, email dated 24 June 2013.]

61

Literally ‘the Norwegian bank of words’. Cf.

http://www.hf.uio.no/iln/om/organisasjon/edd/forsking/norsk-ordbank/ [Accessed 27 March 2013].

62

Literally ‘The Norwegian language bank’, cf. “Språkbanken - a language technology resource collection

for Norwegian”, available at http://www.nb.no/English/Collection-and-Services/Spraakbanken [Accessed

27 March 2013].

63

Formerly called Norsk språkråd.

64

Apart from its use in (computational) linguistics research, both directly and indirectly, for instance via

the Oslo-Bergen-tagger, it has been acquired for commercial use by Abilia, iFinger Ltd., Innovit AS, Lingit

AS, Microværkstedet/Mikroverkstedet, Oribi AB, Ovitas AS, Nynodata AS, Rescudo, and Sticos AS.,

according to Norsk språkbank [Accessed 5. April 2013]. Additionally, it has been used by Wordfeud.

65

With the notable exception of Dokumentasjonsprosjektet and its successor Eining for digital

dokumentasjon, ‘Unit for Digital Documentation’ (University of Oslo), the technical host of Ordbanken.

21

3 Allegations

On the face of it, documentation of digital language resource projects like the one dealt

with above from the beginning of the 1990s would be adequate. In 2002, however, this

author became aware of the following paper, which had been read at the 2000

EURALEX conference and later reproduced in its proceedings:

“On the basis of the lemmas in Bokmålsordboka the IBM-company [sic!] has made

lexical full form lists, which have been further developed through the so called

Documentation project as full fledged morphological bases of the standard forms in

Norwegian bokmål.” (Fjeld 2000, 672)

The author of the paper was informed that IBM did not make lexical full forms lists on

the basis of the lemmas of Bokmålsordboka. Also, that the files received by “the so called

Documentation project” (University of Oslo) already represented a full-fledged

morphological base of Norwegian Bokmål (and Nynorsk as well). She maintained that

there was a lack of documentation as far as the IBM project was concerned, and that there

was nobody there to ask.

Later the same year, a new paper of the same author appeared, where she claimed

“I 1989 sammenliknet man ved IBMs språkavdeling det ordforrådet som lå inne i en

elektronisk versjon av Bokmålsordboka med de formene som faktisk var i bruk i

tekster. (---) IBM arbeidet imidlertid med et språkteknologisk mål for øye, (---) og

utarbeidet deskriptive lister av ordforrådet i løpende tekster. IBM-listene ble seinere

utgangspunktet for de morfologiske basene som Tekstlaboratoriet og

Dokumentasjonsprosjektet ved Universitetet i Oslo har utviklet (---).”(Fjeld 2002,

139)

‘In 1989, IBM’s section for natural languages compared the vocabulary of an

electronic version of Bokmålsordboka with the word forms actually used in texts.

(---) However, IBM had a language technology perspective, (---) and compiled

descriptive lists of the vocabulary in running texts. Later, the IBM lists served as the

point of departure for the morphological bases that were developed by

Tekstlaboratoriet and Dokumentasjonsprosjektet (University of Oslo) (---)’

For anyone without specific knowledge of the reality, the only natural interpretation of

this paragraph will be that IBM compiled lists on the basis of the vocabulary of an

electronic version of Bokmålsordboka, and that this list served as the point of departure

for the morphology developed by the University of Oslo. Again, this is contrary to the

merits of the case.

This incident provoked two conference papers (later published as Engh 2009 and

2011) where things were put straight.