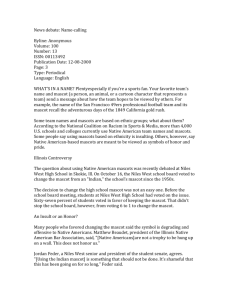

An Analysis of Community Attributes Likely to Result in School... Repealing Native American Mascots

advertisement