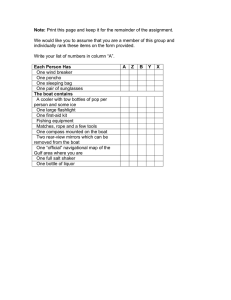

BOAT SEAMANSHIP CHAPTER 5

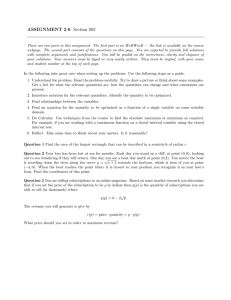

advertisement