Independent Work : Classwork: Homework and Class Work for ORAL COMMUNICATIONS

advertisement

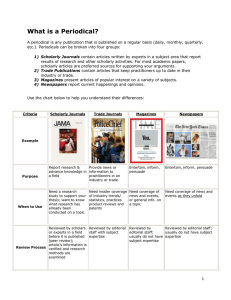

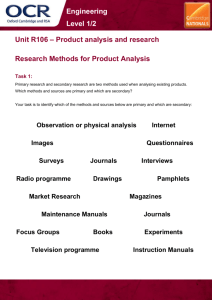

Homework and Class Work for ORAL COMMUNICATIONS 2nd Pd: Haley Banks, Lindsay Goss, Rashelle Caudill, Hannah Mullins Monday, November 4, 2013 4th Pd: Amy Sabon, Summer Goodan 3rd Pd: Annie Dailey, Melanie Fraley Independent Work : See attached Permission Slip for next week’s field trip which is due back Friday, November 8. Classwork: 1. The class went to the library to work on learning the process of Research. 2. The first step in the research process is as follows: STEP ONE: DEFINING THE TASK What do I have to find out? 1. What kind of final product are you expected to present to the teacher? • Is it a written report? • An oral presentation? • A poster? • Or something else? 2. Does it have to be a certain length, size, or duration of time? • Do you have any freedom of choice in how to present what you will learn? 3. What is the topic of the assignment? • Does your teacher give you the specific topic (subject) of your assignment? • Do you have any freedom to select a topic for yourself? • Do you have to create a thesis statement (take a position, make an argument)? • Did the teacher give you a very general topic that you have to focus to a smaller topic? Topic Requirements/Considerations for Oral Comm: a. b. c. d. e. Must be related to your career path, if at all possible Should be unique Should be interesting to an audience Must be significant to today Is there enough research to talk about it? Topic Idea Generator – Go to the following website and explore to help you find ideas for a topic. http://www.lib.odu.edu/researchassistance/ideagenerator/ 4. What is the due date for your final product? • Are there any parts of the assignment due before the final due date (like a rough draft, notes, outline, etc.)? Helpful Hint: Get an assignment calendar and write any due dates in it. This will help you plan your time to get the assignment done by the due date. Most THE CLASS WILL DISCUSS FURTHER DETAILS RE: STEP ONE ON WEDNESDAY. 3.The class then turned the discussion to acceptable sources of information for the informative speech. They are as follows: GENERALLY ACCEPTED SOURCES OF INFORMATION 1. BOOKS Books are excellent sources of information, particularly if you’re looking for a deep and thoughtful analysis. Books take a lot of time to write, and authors have generally thought about the subject matter quite deeply. Books also may have a large scope; it is quite possible that you’ll find a book that covers much more material than you need to answer your question. Be sure to use the index and/or table of contents to help you locate information more precisely. 2. REFERENCE BOOKS Reference books provide overviews on subjects. They do not present original research, and they usually are not read from cover-to-cover. Instead, people refer to them by looking up entries; that’s why they are called reference books. If you need an authoritative overview on a topic, you will be well-served to consult a reference book. 3. ARTICLES Most articles are published in journals, newspapers, magazines and other publications that come out periodically. Thus, they are called periodicals. Periodical literature is usually focused on a specific topic; unlike books, periodical articles are not covering a wide scope. Unlike reference books, periodical articles generally do not provide overviews of topics or introductions to material. Instead, they consist of reports, analyses, or essays on a particular subject, and many of them include a specific point of view. Here are descriptions of the different kinds of periodicals and what they may provide: Popular journals: Popular journals are aimed at the general public. Writers are reporters or journalists, who have spoken with or consulted experts and have written the article so that information is accessible by the public. Examples of popular journals include Time, Newsweek, US News & World Report and other magazines. Popular journals are often available at newsstands or bookstores. Popular journals are visually interesting; they are likely to have glossy pages, photographs, catchy article titles, and advertisements. This is because popular journals have to attract the public in order to sell. Scholarly or peer-reviewed journals: Scholarly journals contain articles that were written by experts, and they are aimed at experts. The information in scholarly journals can be highly sophisticated because the writers assume that their readers already know the basics on a particular topic. Usually, scholarly journals are not found in newsstands or bookstores; instead, they are found in academic libraries, and they generally do not have flashy names. Scholarly journals not commercial in nature; reading scholarly literature is part of the job of scholars, practitioners and other experts, so the journals don’t need to sell themselves. Thus, they generally do not contain advertising, and they also aren’t trying to “hook” their readers with a captivating title or photo. Newspapers: Newspapers contain reports and articles related to current events. They describe significant events for a community, and reporters try to present material without bias. Reporters strive to present facts in their stories, and newspapers often fill people in on recent changes on policies or other noteworthy events. Newspapers generally publish opinion pieces or editorials as well. In these columns, the editors express their opinions about current events, and they provide analysis of the news story. Newspapers are available to the general public. They contain advertisements, but their pages are not glossy or bound. Instead, newspapers are usually discarded by consumers once they’ve been perused. 4. WEBSITES The Internet puts a wealth of information at our fingertips. However, much of that information may be inappropriate for academic research. While there are wonderful and informative websites, there are also many websites that are out-of-date, inaccurate, or biased toward a certain perspective. Moreover, some articles published on the web have gone through an editorial process; others have not been through an editorial process. You can easily find a website that has not been fact-checked or verified, even if it looks polished and professional. Because you cannot be sure if the information published on the web is accurate, you need to evaluate the reliability of the information even before you begin critical reading. As a researcher, your job includes the active evaluation of your resources. You need to be thoughtful when reading websites, and you need to think about whether such information is trustworthy. Don’t turn in projects riddled with misinformation. Flawed material can often came from websites you use. You can’t necessarily take the information as fact, because it often is just someone's personal opinion. 1. How to evaluate a website's credibility. Take specific steps to dissect a website, such as checking whether its URL ends in a .com, .org, .gov, or .edu. If it's from a university, museum, government, or some state run agency, then it's pretty valid. If it's someone's personal website, how do you know what that person is saying is true? In any case, you should approach websites with a critical eye by asking these questions: Who wrote this webpage? Does the author have credentials? Is this webpage affiliated with a credible organization? When was the website last updated? What is the purpose of the organization that is hosting the website? Does the author provide a bibliography? Or else while searching for information on African-American history, you could wind up on the site for the Ku Klux Klan. It's also important to know if a site is commercial. If so, it may be slanted toward having users buy products. Not that advertising on a site makes it less credible, but it's just another point to consider when looking at information. What is the intent of the information? When you take the time to approach your Web research thoughtfully, you sometimes encounter websites that are biased. For example, Ms. Harris, the University Laboratory High librarian, recalls working with a student who was writing a paper on George Orwell's 1984. The boy found an essay about the book on the site of the Institute for Historical Review. Upon closer examination, the website was a Holocaust-denial website, Ms. Harris said. "It looks scholarly because it's called 'institute,' and there are citations at the bottom," she said. Five Criteria for Evaluating Web Pages: Accuracy Authority Currency Objectivity Coverage Use Web Evaluation Checklist to evaluate the following site: malepregnancy.com Turn in your evaluation for credit.