Moneyville Exhibit A Summative Evaluation Report Prepared for

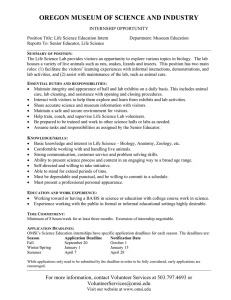

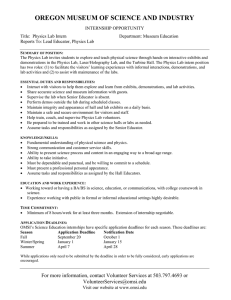

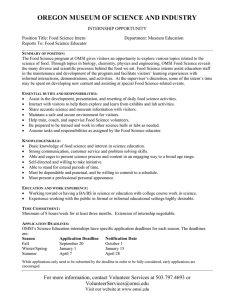

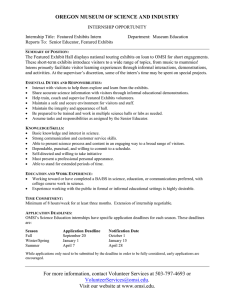

advertisement