South West Dementia Partnership Improving domiciliary care for people with dementia: a provider perspective

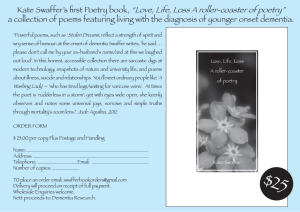

advertisement