The Relation of Weight Suppression and Body Mass Index to

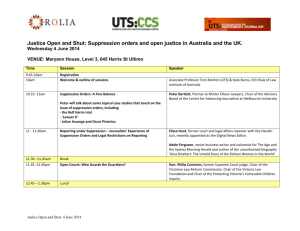

advertisement