The “China Seas” in world ... of the role of Chinese and ...

advertisement

Jo u rn a l o f M arin e a n d Isla n d C u ltu res (2012) 1, 63-86

M A R IN E A N D

IS L A N D C U LTU R ES

Journal of Marine and Island Cultures

www.sciencedirect. com

The “China Seas” in world history: A general outline

of the role of Chinese and East Asian maritime space

from its origins to c. 1800 ^

Angela Schottenhammer

G hent University, Blandijnberg 2, 9000 Ghent, Belgium

R eceived 19 Septem ber 2012; accepted 7 N ov em b er 2012

A vailable online 16 Ja n u a ry 2013

KEYW ORDS

A b s tra c t

C h in a seas;

M a ritim e history;

E a st A sia n M ed iterran ean ;

M a ritim e space;

M a ritim e trad e;

E xchange relatio n s

m a in ta in e d n e tw o rk s o f tr a d e a n d ex ch a n g e re la tio n s . H is to ric a lly , th ese w a te rs c o n s titu te d n o t

T h ro u g h th e E a s t A s ia n w a te rs its n e ig h b o u rin g c o u n trie s h a v e since ea rly tim es o n

o n ly a k in d o f b o r d e r o r n a tu r a l b a r rie r b u t f ro m v ery e arly tim es o n a ls o a m e d iu m fa c ilita tin g

a ll k in d s o f e x c h a n g e s a n d h u m a n a c tiv itie s, a m e d iu m t h r o u g h w h ic h in p a r tic u la r p riv a te m e r ­

c h a n ts b u t a ls o g o v e rn m e n ts a n d o fficial in s titu tio n s e s ta b lis h e d c o n ta c ts w ith th e w o rld b e y o n d

th e ir b o r d e rs . T h e seas w ere so m e tim e s c o n s id e re d a b a r r ie r b u t a b o v e all a c o n ta c t zo n e , a m e d iu m

th a t d e s p ite its d a n g e rs a n d d ifficu lties e n a b le d p e o p le to e s ta b lis h a n d m a in ta in m a n if o ld ex ch a n g e

re la tio n s.

T h is a rtic le in te n d s to p r o v id e a g e n e ra l o u tlin e o f th e h is to ric a l ro le a n d significance o f E a st

A s ia n m a ritim e sp a ce f ro m its o rig in s to a p p ro x im a te ly 1800, in c lu d in g th e E a s t C h in a S ea, th e

B o h a i S ea, th e Y e llo w S ea (H u a n g h a i), th e s o u th e rn se c tio n o f th e J a p a n e s e S ea, a n d p a r ts o f

th e S o u th C h in a S ea (n o w u su a lly c a lle d N a n h a i) . I t fo cu ses especially , a lth o u g h n o t exclusively,

o n C h in a ’s tr a d itio n a l tr e a tm e n t o f a n d refe re n c e to th is m a ritim e re a lm . A lso in o r d e r to m a in ta in

th e s p a tia l c o n c e p t o p e ra b le , w e h a v e d e c id e d to c a ll th is m a ritim e sp a ce th e “ C h in a S e a s” .

© 2012 In stitu tio n fo r M a rin e a n d Isla n d C ultures, M o k p o N a tio n a l U niversity. P ro d u c tio n a n d h o stin g

by Elsevier B.V. A ll rig h ts reserved.

E -m ail address: an gela.schottenham m er(® ugent.be.

* T his study co n trib u te s to the M C R I (M ajo r C o llab o rativ e R esearch Initiative) p ro ject spo n so red by the Social Sciences a n d H u m an ities

R esearch C o u n cil o f C a n a d a , carried o u t a t the H isto ry D e p a rtm e n t, In d ia n O cean W o rld C entre (IO W C ), M cG ill U niversity. T his p a p e r was

originally p resen ted u n d er the title “ T he C hinese ‘M e d ite rra n e a n ’; T he C h in a seas in w orld history (from its origins to c, 1800)’’ a t E m o ry

U niversity, A tla n ta , U S A , In te rn a tio n a l C onference “ Sea R overs, Silk a n d S am urai: M a ritim e C hina in G lo b al H isto ry ", 27-29.10.2011,

28.10.2011.

P eer review u n d er responsibility o f M o k p o N a tio n a l U niversity.

Production an d h o stin g by Elsevier

2212-6821 © 2012 In stitu tio n for M a rin e a n d Isla n d C u ltu res, M o k p o N a tio n a l U niversity. P ro d u c tio n a n d h o stin g by Elsevier B.V. A ll rig h ts reserved.

http://d x .d o i.O rg /1 0 .1 0 1 6/j.im ie.2012.ll.002

64

A. S chottenham m er

Introduction

E ast A sia is a region th a t has recently gained increasing g eo p o ­

litical im portance a n d in the course o f g lobalization m ay well

becom e the new w orld-centre in the fu tu re .1 T h ro u g h th e E ast

A sian w aters its neig hbouring countries m ain ta in to d ay a g lo ­

bal n etw o rk o f trad e a n d exchange relations. B ut in teg ratio n

into local an d supra-regional netw orks is n o t only a m o d ern

phenom enon. Elistorically, these w aters co n stitu ted n o t only

a kind o f b o rd e r o r n a tu ra l b arrier b u t from very early tim es

on also a m edium facilitating all kinds o f exchanges a n d h u ­

m a n activities, a m edium th ro u g h w hich in p artic u la r private

m erchants b u t also governm ents a n d official institu tio n s e sta b ­

lished contacts w ith the w o rld b eyond th eir borders. G enerally

speaking. E ast A sian m aritim e space w as used by fisherm en,

private an d official trad ers, governm ents (nations) a n d g overn­

m ent institutions, p irates, a n d travellers fo r b o th com m ercial,

m ilitary, diplom atic a n d p rivate purposes, such as m ig ratio n

o r voyages. The seas were som etim es considered a b arrier

b u t above all a contac t zone, a m edium th a t despite its dangers

an d difficulties enabled people to establish a n d m ain tain m a n ­

ifold exchange relatio n s.2 This article intends to provide a gen­

eral outline o f the historical role a n d significance o f E ast A sian

m aritim e space th a t includes the E ast C hina Sea, the B ohai ?|j]

Sea, the Y ellow Sea (E luanghai If'jJf), th e so u th ern section

o f the Japanese Sea, a n d p a rts o f the S o u th C hina Sea (now

usually called N an h a i IffjJf), focussing especially, alth o u g h

n o t exclusively, on C h in a ’s tra d itio n a l treatm en t o f a n d refer­

ence to this m aritim e realm . A lso in o rd er to m ain tain the sp a­

tial concept operable, we have decided to call this m aritim e

space the “ C hina Seas’’, a term th a t m ay n o t be m isu n d ersto o d

in the sense th a t this E ast A sian b o d y o f w ater as a w hole o r all

o f the sections th a t we address in this p a p e r a t any tim e b e­

longed to C hina o r w ere p a rt o f C hinese sovereignty.3 N o t­

w ithstanding the fact th a t the focus o f this article lies in the

im portance a n d role o f m aritim e space fo r a n d in C h in a’s his­

tory, we will now a n d again also discuss developm ents th a t

to o k place in Japanese o r K o re a n co astal w aters.

A t the sam e tim e, it m ay at least n o t be neglected th a t d u r­

ing p ro b ab ly m o st o f the tim e periods from a n tiq u ity th ro u g h

the m iddle to the early m o d ern perio d it w as in fact C hina th a t

w as the, if n o t alw ays political, b u t a t least econom ic a n d cul­

tu ral centre o f the m acro-region, w hich - alth o u g h it w as

undou b ted ly prim arily a co n tin en tal p ow er - w as also quite ac ­

tive in m aritim e space.

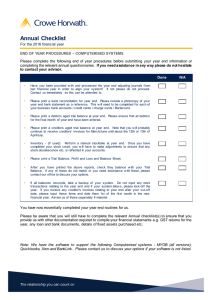

K O REA

JA PA N

East China Sea

CHINA

Fujia

Pacific Ocean

Inom w e

^ « -M iy s fc o

a ^A-C^-Uhigaki SaJ

TA IW A N

-N -

East China Sea Region

F irst being a regional “ M ed ite rran e an ’’,4 the C hina Seas

soon developed as a sprin g -b o ard an d startin g -point for

long-distance trad e, a n d by Song tim es a t the latest w ere firmly

in teg rated into the w orld-w ide exchange system as it existed at

th a t tim e, a n “ in te rn a tio n a l’’ exchange system th a t adm ittedly

w as n o t yet a global one b u t th a t w as “ substantially m ore com ­

plex in organ izatio n , greater in volum e, a n d m o re sophisti­

cated in execution, th a n anything the w o rld h a d previously

k n o w n ’’.5 R egional seas grew m o re an d m ore to g ether an d

w ere gradually in teg rated in to global structures - w ith in ter­

ru p tio n s a n d setbacks o f course.

This brings us to th e qu estio n o f sea routes, w hich can u n fo r­

tu n ately n o t be discussed in m ore detail w ithin the scope o f this

article. Basically we can discern n o rth e rn , eastern, so uthern an d

w estern routes, w hich can generally be sum m arized as follows:

1 The “ n o rth e rn ro u te s’’ (beihang hi

la F ro m F u jian fmi®, Z hejiang ?}/rïI a n d Jiangsu ÎX Ü , or

from S h andong [ X lí, to the eastern a n d so u th ern coasts

o f K o rea a n d fu rth er to Ja p a n (E lakata

N agasaki

Ä ß)

1 T his is also reflected by discussions a b o u t a n E ast A sia n in te g ra ­

tio n . beginning w ith a u n ifo rm m a rk e t a n d gradually developing in to a

closer p o litical an d m ilitary c o o p eratio n , sim ilar to the E u ro p e a n

U n io n . E ven ideas like a n E ast A sia n currency (sim ilar to the E uro)

have b een raised.

2 See A ngela S ch ottenham m er. R o d e rick P ta k (Eds.). M aritim e

Space in Traditional Chinese Sources. in: E ast A sian M a ritim e H istory.

(W iesbaden: O tto H arrasso w itz, 2006). vol. 2.

3 W e are well aw are o f the fact th a t th e sp atial concept o f E ast A sia

itself is a highly com plex a n d n o t u nproblem atic one.

4 W hen we speak o f a n E a st A sia n “ M e d ite rra n e a n ", a term b o rro w ed

fro m the F re n c h h is to ria n F e rn a n d B rau d el th a t co n n ected the

n eigh b o u rin g countries in the m acro-region, the term is used only as a

m ethodological to o l to em phasize th e b ro a d variety o f m u lti-layered

exchange relations. F e rn a n d B raudel (1902-1985). L a M éditerranée et le

m onde m éditerranéen à l ’époque de Philippe II. (Paris: 1949; Paris.

A rm a n d C olin. Le Livre de poche. 1990. rééd.). vol. 3.

3 A b u -L u g h o d , Ja n et. B efore European H egem ony. The W orld S ystem

A .D . 1250-1350. (New Y ork: O x fo rd U niversity Press. 1989). 353.

The “ C hina Seas’’ in w o rld history: A general outline

asa

„as

Portugal

65

**«

N“*»

SP *"/

£14IS ( » iii

•

R I B (**>

(4 * 1

i* * “

«M*

ungiMu

£*»«»«

Saudi Aral**

lV.Hl SB J

IC«H) • ,

H I*

A*

ft

P acific O c ia n

'm

5<iuiti China

" WHÊ*

A »

Afnf »

;

X to r i*

Bay of Bengal

A/jtunSH

I CM«) .

\ /

*

*■=*

S/iUtik*

<*tt*

.

/ Philippinei

.....

**'0W\

»*14

Indian Ocean

Atlant* Ocean

_ _ _ _ _

» f f « » » . 'SARU

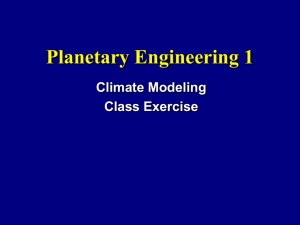

The S e a Communication Chart of Asia belonging to th e Tang a n d S ong dynasties.

- F ro m D engzho u S;lT[ a n d Penglai S lstl in S h andong

along the B ohai a n d D a lian Bay iK M t t to the m o u th

o f the Y alu R iver

- F ro m Jiangsu or Z hejiang via F luksan ü l Li Ï J to the west

coast o f K orea

lb The “ eastern ro u te ’’ (donghang lu

from F u jian

or Z hejiang via th e R yükyüs to so uth ern Ja p a n

2 E astern routes (also donghang lit)

2a F ro m F u jian via the n o rth e rn tip o f T aiw an to N a h a §13

H on the R yükyüs

2b F ro m F u jian a n d Z hejiang directly to so u th ern Ja p a n

3 S outhern routes (nanhang lu IflÂ/tfô)

3a The “ eastern ro u te ’’ (again donghang lu) fro m F u jian to

L uzon an d the Sulu region

3b The so-called “ w estern ro u te ’’ (xihang lu Ë3ÎTÏ&) from

Jiangsu via Z hejiang, F u jian , G u an g d o n g a n d th e n fu r­

th er to the S o u th C hina Sea - via Flainan, V ietnam a n d

the area o f m o d ern S ingapore - a n d to the In d ian O cean

(this ro u te h ad m an y branches w ithin S o u th east A sia)6

6 A ngela S ch o tten h am m er. “ T he Sea as a B arrier a n d C o n tac t Zone:

M aritim e Space a n d Sea R o u tes in T ra d itio n a l C hinese Sources an d

B o o k s". 9. in A ngela S chottenham m er. R o d e rich P ta k (eds.), M aritim e

Space in Traditional Chinese Sources: see also the m any p u b licatio n s o f

R o d e rich P ta k th a t discuss sea ro u tes, fo r exam ple. China, the

P ortuguese, and the N anyang. Oceans and R outes, R egions and Trade

( c. 1000-1600). (A ldershot, etc,: A shgate P ublishing L td .. 2004).

V a rio ru m C ollected Studies Series CS 111: R o d e rich P ta k . “ Jo ttin g s

o n C hinese Sailing R o u tes to S o u th east A sia. E specially on the E astern

R o u te in M in g T im es", in Jorge M . dos S an to s A lves (coord.).

P ortugal e a China .Conferencias nos encontros de historia luso-chinesa.

(Lisbon: F u n d a ç à o O riente. 2001). 107-131; “ T he N o rth e rn T rade

R o u te to the Spice Islands: S o u th C h in a Sea - S ulu Z one - N o rth

M oluccas. (14th to early 16th C e n tu ry )". A rchipel 43 (1992). 27-56.

M an y guides an d descriptions o f sea ro u tes existed in C hina.

A n an o n y m o u s M ing m ap , fo r exam ple, the Gu hanghai tu

kaoshi

shows the tra d e arteries fro m the B ohai

area dow n to the m o u th o f the P earl R iver n e a r G uangzhou.

In som e cases, th e ro u tes are depicted as lines (chuanlu !□£&),

in others they are described in w o rd s.7 Sea ro u tes o f course

also som etim es changed over tim e a n d w ith th em the in- or

decreasing im portance o f coastal a n d p o rt cities. In fo rm atio n

o n sea routes a n d coastlines w as com piled into ro u te m aps,

star ch arts, a n d “ com pass-needle m a n u a ls’’ (zhenjing ill® )

o r so-called “ ru tte rs’’.8 D u rin g th e fam ous expeditions led

by Z heng H e Jt|3j€ (1371-1433), fo r exam ple, a n enorm ous

q u a n tity o f in fo rm atio n on sea routes a n d coastlines w as col­

lected a n d com posed as ru tters a n d m aps. U n fo rtu n ately ,

m uch o f this geographical m aterial w as late r b u rn t by the

M in ister o f W ar, L iu D axia ÿilK M . (1437-1516). N everthe­

less, the geographical know ledge related to th em w as n o t en ­

tirely lost.

T he condition sine qua non fo r the practical use o f m aritim e

space were b o ats a n d ships. W hen exactly the Chinese first

7 T im othy B ro o k . Geographical Sources o f M ing-O ing H istory. (A nn

A rb o r: C e n te r for C hinese Studies. T he U niversity o f M ichigan. 1988).

43.

8 T he first p rin te d ru tte r w as ap p aren tly the D uhai fangcheng

I I by W u P u í l j'f '. w hich w as pu b lish ed in 1537. Cf. T ia n R u k a n g ES

Ä J * . “D uhai fangcheng - Z h o n g g u o diyiben keyin de sh uilubu Ï Î Î Î 7 J

11 - S^SSI?— iS 'jË P É L U k fô îî" . in Li G u o h a o

et aí. (eds.).

E xplorations in the H istory o f Science and Technology in China.

(Shanghai: S hanghai guji chubanshe, 1982). 301-308. I t is also briefly

discussed in T im othy B ro o k . “ C o m m u n icatio n s a n d C o m m erce", in

D enis T w itchett a n d F re d erick W . M o te (eds.). 1998. The Cambridge

H istory o f China, vol. 8: The M ing D ynasty, 1368-1644, P a rt II.

(C am bridge: C am bridge U niversity Press). 579-707. 696-691.

A. S chottenham m er

66

I

2 # [fcO-7 4 * S J 5 2 ' J ] . Kraft-Katalog Nr. 274; KS

7/295/4 (Muromachi monogatari); NSN 13f; Sawai 2 S. 101-130; Mjm 5

Nr. 103; A 27. Reprinted with kind permission of the Staatsbibliothek

Preußischer Kulturbesitz Berlin (Libri japon. 450).

began to build b o ats is hard ly reconstructable. E arly sources,

generally speaking, co n tain little evidence on ships o r seafar­

ing. T he Yijing

(chapt. Xici S l f ) traces ships fo r tra n s ­

p o rta tio n purposes b ack to the tim e o f the Y ellow E m p ero r

(Eluangdi H i ) . T he Shijing ¡#£5 contains various references

to b o ats a n d ships.9 B ut these very sh o rt entries c an n o t provide

any fu rth er in fo rm atio n a b o u t shipbuilding; in ad d itio n , they

m ostly refer to river shipping. V arious archaeological relics

including bo ats, oars, a n d ru d d e rs10 d atin g to periods betw een

6000 an d 2000 BC, encouraged C hinese scholars to conclude

th a t already during the earliest tim es o f C hinese civilization,

d u ring the X ian to u lin g Ä S I 5 I culture (6500-5000 BC), in

G u an g zh o u dug -o u t canoes w ere used to venture into the open

w aters. B ut even w hen we assum e th a t these dates are correct,

they do n o t allow any fu rth e r conclusions concerning ship­

building. A rchaeologists fu rth erm o re fo u n d m etal rings d atin g

to the W arrin g States P erio d (475 or 463-221 BC) th a t su p p o s­

edly were used to fortify ship p lan k s.11 B ut we do n o t possess

any definite p ro o f fo r this. It w ould seem to be safe to say only

th a t by Shang tim es at the latest (16th—11th centuries BC) the

coastal p o p u latio n used simple devices to float along the c o ast­

al w aters.12

W ritten sources only rarely speak a b o u t co n stru ctio n form s

o f ships (for exam ple Shiji, chap t. 30 a n d 118). The “ first sea­

w o rth y vessel’’13 according to som e C hinese h istorians, is re ­

corded in the Bamboo Annals (Zhushu jinian

com posed at the tim e o f the W arrin g S tates.14 W hen H u an g d i

TC^r ascended the th ro n e, a big fish th a t h ad been cau g h t in

9 Jam es Legge. The Chinese Classics. W ith a Translation, Critical and

E xeg etica l N otes, Prolegom ena, and Copious Indexes, in Five V olum es,

vol. IV . The She King. (R eprint. T aibei: S M C P ublishing. 1992). vol.

IV . 38. 71. 74. 102. 280. 338. 404. 435. 443.

10 X i L ongfei JffiÜ/fls. Z hongguo zaochuan shi ^ S S l M n Í ! . (W uhan:

H u b ei jia o y u ch u b an she, 2000). 2.

X i L ongfei. Z hongguo zaochuan shi, 38.

" X i L ongfei. Z hongguo zaochuan shi, 21. 27-29.

13 G a n g D eng. Chinese M aritim e A ctivities and Socioeconom ic D evel­

opm ent, c. 2100 B .C -1 9 0 0 A .D . (W estport. C o n n ecticu t. L ondon:

G reen w o o d Press. 1997). 23.

14 G a n g D eng. Chinese M aritim e A ctivities and Socioeconom ic D evel­

opm ent, 22-23.

the coastal w aters, w as rep o rted ly sacrificed.15 K ing M an g

C is recorded as having cau g h t a big fish in the sea.16 B ut such

entries o f course provide n o valuable in fo rm atio n concerning

shipbuilding.

A sp ectacular find w as excavated in 1974 in G uangzhou,

w hen archaeologists discovered th e rem ains o f an old shipyard

th a t w as d ate d to the tu rn o f the second to th ird century B C .17

A ccording to estim ations ships o f a length o f u p to 30 m a n d a

w id th o f 8.4 m could have been co n stru cte d th e re .18 In situ v a r­

ious Q in a n d H a n coins, c arp en ters’ tools, arro w heads an d

daggers w ere excavated. T h ro u g h com p arativ e analysis schol­

ars concluded th a t this w as m o st p ro b ab ly a state-supervised

shipyard used fo r m ilitary p u rp o ses.19

E ventually, du rin g H a n tim es, shipbuilding technology w as

o n a g reat upsw ing. P rogress w as m ade n o t only in term s o f

hull co n stru ctio n , m asts, rudders, oars o r sails. B ut, as w ritten

sources confirm , there existed different types o f ships th a t

could be used fo r different fu nctional p urposes - naval, com ­

m ercial, fo r com m odity o r h u m a n tra n sp o rta tio n across sm all

an d large rivers or coastal w aters.20

13 G a n g D eng. Chinese M a ritim e A ctivities and Socioeconom ic D evel­

opm ent, 23; Z hushu jinian tongjian

by X u W enjing

Sra- (Taibei: Y iw en y inshuguan 1966). j . 1, 5a (87).

16 Z hushu jinian tongjian, j . 3. 18a (181).

17 T h o m as H ö llm an n , “ P anyu: D ie südliche P forte n ach C h in a

w äh ren d der H a n -Z e it", in M a rg arete P rü ch , u n ter M ita rb e it v on

S tep h an v o n der S chulenburg (ed.), Schätze fur K önig Z ha o M o. D as

Grab von N an Yue. (H eidelberg: B rau s V erlag. 1998). 109-113. here

110; G u a n g z h o u w enw u guan lich u JífK ífcíS líT iJÉ L “ G u an g zh o u

Q in H a n zao ch u a n gongchang yizhi shijue J * f K l i í J t j o |n I í í j j S í l t 'i Í

ÍS " . W enwu 4 (1977). 1-16.

18 G a n g D eng. Chinese M a ritim e A ctivities and Socioeconom ic D evel­

opm ent, 77.

19 G u a n g z h o u w enw u guanlichu. “ G u a n g z h o u Q in H a n zao ch u a n

gongchang yizhi shijue".

20 L in F en g jian g Í 4 M Í I . C h e n X iu ju a n

“ H a n d a i de zaochuanye yu haiw ai m aoyi Í J t f t jo f tn lS Í ^ Í f

Longjiang sheina

ke x u e il} IÜ ifig rf 4 '¥ 6 (1994). 65-67.

The “ C hina Seas” in w o rld history: A general outline

E ssential fo r sailing th e seas were the periodic m o n so o n

w inds, w hich determ ined seafaring all over the In d ia n O cean

over centuries.21 These w inds com prise a system o f regularly

altern atin g w inds an d currents u nique to the In d ia n O cean

an d S outh an d E ast C hina Sea. F ro m A pril to Septem ber, as

the A sian land m ass heats up, h o t a ir rises pro d u cin g a v ac­

uum , w hich sucks in the a ir from the ocean, creating the so u th ­

w est m onsoon. D u rin g th e o th er six ‘w in ter’ m o n th s o f the

year, the o pposite reactio n occurs, creating the n o rth e a st m o n ­

soon. T hey were later called xinfeng ÍE & (reliable w inds), jifeng

(seasonal w inds) o r maoyifeng M SiM , (trade w inds)

in Chinese. E arly evidence th a t th e C hinese knew a b o u t these

w inds can be fo u n d in the Shiji. I t m entions the n o rth w est

w inds

the n o rth w inds

the n o rth e a st w inds

IS M , the east w inds

the so u th east w inds

the

east w inds ÍR M , the southw est w inds î f l f i a n d the w est w inds

MUM.22

B ut the invention o f the sail constitutes a problem . W e can

only speculate th a t p ro b ab ly as early as S hang tim es simple

form s o f sails were in use.23 F u n ctio n al sails were pro b ab ly

n o t used before the fifth century BC, certainly late r th a n in

E gypt.24 Scholars basically agree th a t sails were m o st pro b ab ly

invented by n o n H an-C hinese peoples such as the Y ue M . This

co ntrad icts the legend th a t the sail (fan ifiFL) h a d already been

invented by the G rea t Y u

durin g the X ia M D ynasty

(trad. 2205-1766).25

Early mythology and ideology

A lready in the first m illennium BC the sea h ad a definite place

in C hinese ideology. A bronze inscription from the 10th cen­

tu ry BC m ention s the term “hai A “ already in its m eaning

as “ sea” , while the term “yang A “ is still restricted in m eaning

to signify a “ vast, expansive space” .26 The earliest C hinese lit­

erary source attesting to the fact th a t the sea w as originally re ­

g arded as a kind o f frontier, m argin, o r delim itation - a n d a t

21 T he m o n so o n w inds w ere k n o w n to m o st o f the seafarers. G reeks

a n d R o m an s knew th e w inds according to its “ discoverer” H ippalos,

w h o p ro b ab ly lived in th e first cen tu ry BC. H e d a re d to sail over the

o p en sea a n d cou ld , th u s, sh o rte n trem endously th e sea voyage to

In d ia. A lso th e In d ian s knew a b o u t th e m o n so o n w inds a n d highly

resp ected th e sto rm y so u th w e st m o n so o n . B o th th e an o n y m o u s

co m po ser o f th e Periplus o f the Erythraen Sea as well as P linius the

O lder in his N atural H istory d istrib u ted the discovery o f these w inds” .

F o r d etails see fo r exam ple D ie tm a r R o th erm u n d , “ D er Blick vom

W esten a u f d en In d isch en O zean v o m < P eriplus > bis zur < Sum a

O rien tal > ” , in D ie tm a r R o th e rm u n d , S usanne W eigelin-Schw iedrzik

(H rsg.), D er Indische Ozean. D as afro-asiatische M ittelm eer als Kulturund W irtschaftsraum. (W ien: P rom edia, 2004), 9-35.

22 Shiji, j . 25, 1243-1248. A ccording to G a n g D eng 1997, 43, the

m o n so o n w inds w ere called bozhuo fen g

in sayings o f the

p e a sa n t p o p u la tio n d u rin g H a n tim es. T his w o u ld im ply know ledge

a n d d istrib u tio n o f th e ch aracter $10.

X i L ongfei, Zhongguo zaochuan shi, 48-50.

G a n g D en g , Chinese M aritim e A ctivities and Socioeconomic D evel­

opment, 32; L in H u a d o n g W ï j f ï , “ Z h o n g g u o fengfan tan y u a n

H aijiaoshi yanjiu i l x i SftjH 2 (1986), 85-88; X i Longfei,

Zhongguo zaochuan shi, 51-52.

25 O n th e in v en tio n o f th e sail d u rin g Shang tim es, see X i Longfei,

Zhongguo zaochuan shi, 49-50.

26 B e rn h ard K arlg re n , “ G ra m m a tic a Serica R ecensa” , Bulletin o f the

M useum o f Far Eastern Antiquities 29 (1957), 947 a n d 732.

67

the same tim e as a m ythological place - is the D ao ist w o rk Liezi ^!l~p (3 rd -4 th century BC; fl. 398 BC), w hich refers to five

m o u n tain s in the m iddle o f a n abyss b eyond the B ohai Sea

(lil'Ä in the E ast - the first one D aiy u Î 5 Ü , the second Y uanjia o MIS, the th ird F an g h u T r is , the fo u rth Y ingzhou

a n d the fifth Penglai ä ls tl.27 The E astern Sea w as considered

the fro n tier o r m arg in to w ard s im m o rtality a n d a space in

w hich the islands o f the im m ortals are located - Penglai M

5tï, F an g zh an g J i 3 t a n d Y ingzhou IHI'M- T om b N o. 1 from

the M aw an g d u i M i i # com plex con tain ed a m u ral w ith a re p ­

resen tatio n o f the Penglai Islands. In C hinese m y thology these

w ere considered the em pire o f im m o rtality w here the elixir o f

im m o rtality could be fo u n d .28 Q in Shihuang itÎ tê M (r. 2 2 1 210 BC) is said to have searched fo r these islands to o b tain

the im m o rtality drug. Sim ilar stories are rep o rted a b o u t E m ­

p ero r H a n W udi îJ tife ir (r. 140-87 B C ).29 In 130 BC, a certain

Li S haojun

to ld the em p ero r a b o u t the process o f

ob tain in g im m o rtality as supposedly also carried o u t by C h i­

n a ’s first a n d m ythical em p ero r H u an g d i Ä S . These stories

a t least reveal th a t the sea seems to have possessed quite a

strong m agical-m ythological a ttra c tio n fo r C hinese em perors

a n d o th er m em bers o f the social elite. T hey also a tte st to their

interest in a w o rld beyond - be it a m ythical one o r a vast u n ­

k n o w n w orld beyond C h in a ’s borders. Interestingly, these

m ythical ideologies all refer to the E astern Sea (donghai Í

:fiI), the d irection in w hich the sun rises. A ccording to Chinese

views C hina w as su rro u n d ed by th e F o u r Seas (sihai E9'Ä), lo ­

cated close to three oceans (yang A ) . T he E astern Seas in ­

cluded the B ohai Jfjl'jJf Sea, the H u an g h a i m A Sea or

Y ellow Sea, the D o n g h ai ^ . A Sea or the E ast C hina Sea

a n d the N an h a i Ifl'ilf o r S o u th C hina Sea.

Early imperial China (Qin-Han)

T he first contacts on sea ro u tes w ere o f course established w ith

close neighbours in the region. F ro m appro x im ately the fo u rth

century BC relatively lively shipping developed in the N o rth ­

east A sian w aters, in p artic u la r betw een C hina a n d K orea.

O riginally, the increase in shipping activities in the E astern

Seas certainly also has to be traced b ack to E m p ero r Q in Shih u an g d i’s itÎ tê M (r. 221-210 BC) search fo r the islands o f the

im m ortals. The sea ro u te led fro m S han d o n g either via various

sm all islands o r directly along the coastline in the d irection o f

K o re a .30 V ia K o re a C hinese influence eventually also reached

Ja p a n , b u t we still know relatively little a b o u t concrete routes

a n d co n tac t in this early period. T he first h u m a n m ovem ents

a n d m ig ratio n to Ja p a n from the C hinese m a in la n d also to o k

place via K o rea. In ad d itio n , the sea w as fro m early tim es o n ­

w ards used fo r com m ercial a n d m ilitary purposes. B ut it m ust

be m en tio n ed th a t in term s o f m aritim e com m erce the Chinese

27 L iezi t y i f , in Z huzi jicheng §)j~Eliijfe. (Beijing: Z h o n g h u a shuju,

1954), vol. 3, chpt. 5 (Tangwen diwu ÎHPoISîIÏl), 52.

28 M ichel L oew e, W ays to Paradies. The Chinese Quest f o r Im m or­

tality. (R ep rin t, Taibei: S M C Publishing, 1994), 37.

29 Hanshu í H # by B an G u ifi[H (32-92). (Beijing: Z h o n g h u a shuju,

1964), j . 25B, 22a (according to L oew e, 37).

30 Z h an g X u n jjüül, Woguo gudai haishang jiaoton g

S - (Beijing: S hangw u yinshuguan, 1986), 1-2; YÜ Y ing-shi, Trade and

Expansion in H an China. A Study in the Structure o f Sino-Barbarian

Economic Relations. (Berkeley, L os A ngeles: U niversity o f C alifo rn ia

Press, 1967), 182.

A. S chottenham m er

68

rem ained relatively passive un til appro x im ately the 11th cen­

tury. They seem to have trad ed early o n (in the Q in -H an p e r­

iod) w ith locations in K o re a an d a b it later also Ja p a n , b u t did

n o t venture to trad e w ith S o u th east A sia, n o t to speak o f the

In d ian O cean, until the la tte r h a lf o f the 11th century. In this

context, one should m ake a d istinction betw een C hinese activ­

ities in N o rth e a st A sia a n d S o u th east Asia.

In search o f the wealth o f the south

E arly contacts w ith S o u th east A sia basically w ent via the

South C hina Sea an d C a n to n o r P an y u W-ßt as the m a jo r po rt.

O n P an y u the fam ous h isto rian Sim a Q ia n B jJ f S (145-86 BC)

rep o rts th a t it co n stitu ted a n im p o rta n t com m ercial centre

w here pearls (zhuji EfeiH), rhinoceros h o rn (xi JÇ), tortoise

shells (daimao Iftlg ), fruits a n d fabrics (guo hu

were ex­

changed.31 B ut com m ercial relations becam e really im p o rta n t

betw een S outh C h in a (G uangdong), In d o -C h in a an d the M a ­

lay A rchipelago only a t the beginning o f o u r time. In 111 BC

E m p ero r H a n W udi subjugated the N an Y u e M U E m pire in

the south to get access to the w ealth fro m the N a n h a i region.

W e know th a t in 29 A D Jiao zh o u 5¿Pit (m o d ern V ietnam ) u n ­

der the supervision o f its local g o v ern o r still volu n tarily sent an

em bassy to the H a n c o u rt “ paying trib u te ” (5¿PltíX §Pl8$"fc

ëP y fe^F jafiË ^Jt)-32 A t th a t tim e m an y C hinese h a d already

m igrated to the region fro m the n o rth . B ut soon problem s a r ­

ose an d W udi sent a punitive m ission to the so u th (see below).

L ater descriptions provide evidence th a t the C hinese were, for

exam ple, especially interested in the co p p er w ealth o f the

region.33

M an y C hinese histo rian s claim th a t the m erch an t ju n k s

(guchuan ID Id) th a t were also used by H a n envoys aro u n d

100 BC w ere b u ilt in C hina an d o p erated by C hinese sailors.

T he Official H istory o f the Han D ynasty, the Hanshu Î J ® ,

how ever, clearly states th a t these envoys h a d to rely o n foreign

“ b a rb a ria n ju n k s” (manyi guchuan S U H f p ) to travel along

the coasts. Still the T an g perio d Tang yulin jiF¡liW¡ by W ang

D an g i l l refers to “ foreign ships called haibo jíflfÉ” , w hich

year fo r year com e to G u an g zh o u fo r trad e, the largest ones

com ing from the “ L io n ’s C o u n try ” (Shizi guo I f i H ) , th a t

is Sri L anka. W henever these o r o th er foreign ju n k s reached

G u angzhou, the local p o p u la tio n w as full o f excitem ent.34

H ep u izrîjt in So u th C hina w as very fam ous fo r its richness

in pearls.35 Even th o u g h it w as econom ically speaking ra th e r

a n undeveloped region - fav o u red as a place o f exile fo r offi-

31 Shiji ÎÈ g2 by Sim a Q ia n KLUIS (145-86 BC). (Beijing: Z h o n g h u a

shuju, 1994), ƒ 129, 3268.

32 H ou Hanshu fl'? # l r by F a n Y e ?B0f (398-446). (Beijing: Z h o n g h u

shuju, 1985), j . 1 shang, 41.

33 H e rb e rt F ra n k e , Geschichte des Chinesischen Reiches. Eine D ar­

stellung seiner Entstehung, seines Wesens und seiner Entwicklung bis zur

neuesten Z eit. (2nd ed itio n o f th e new , revised edition. Berlin, N ew

Y ork : W alter de G ru y ter), vol. 1, 390-391.

34 F o r fu rth er details cf. Jam es K . C hin, “ P o rts, M e rch a n ts, C hief­

tain s, a n d E u n u ch s. R eading M a ritim e C om m erce o f E arly G u a n g ­

d o n g ” , in Shing M ü ller, T hom as, O. H ö llm a n n P u ta o G u i (Eds.),

Guangdong: Archaeology and Early Texts [Archäologie und frühe

Texte], (W iesbaden, O tto H arrasso w itz, 2004), 217-239, 222-223.

35 H ou Hanshu, j. 76, 2473; E d w a rd Schafer, “ T h e P earl F isheries o f

H o -p ’u ” , Journal o f the American Oriental S ociety 72:4 (1952), 155—

168.

cials w ho h a d fallen in to disgrace - the p earl fishing w as very

lucrative. O n H a in a n Island, th a t w as called Z huyai Bfc/li a t

th a t tim e, tw o com m anders, Z h u y ai a n d D a n ’er fltE f were

established. B ut due to revolts b o th com m anders were sus­

p en d ed again in the first century BC a n d all the evidence we

possess suggests th a t the island did n o t play a n im p o rta n t role

in C h in a’s early sea routes th a t ra th e r used to follow the c o ast­

al line to the south.

P ro b ab ly the m o st im p o rta n t source concerning C h in a’s

m aritim e co n tacts a n d ro u tes in the N a n h a i region during

the H a n D y n asty is p rovided by a m uch q u o te d a n d discussed

entry in the Hanshu. Scepticism a b o u t th e auth en ticity o f the

passage as well as th e assu m p tio n th a t it w as n o t actually w rit­

ten by B an G u MISI (32-92) him self has been raised. B ut there

can be little d o u b t th a t the en try provides a relatively authentic

p icture o f C h in a ’s m aritim e relations a t th a t time. C ontacts

w ith places in In d o -C h in a, N o rth S u m atra, M y a n m ar an d

S o u th In d ia are m en tio n ed .36

Follow ing this en try in the Hanshu a n d co m paring it w ith

archaeological evidence along the coasts o f S o u theast A sia

an d In d ia, ships in these tim es sailed from H ep u n “® o r X uw en

first to F u n a n

(Phnam ; S o u th ern A nnam ),

the first im p o rta n t k ingdom in S o u th east A sia,37 a n d then

reached Oc Eo, the p o rt o f F u n a n .38 F ro m there they travelled

via the G u lf o f T h ailan d to the E ast co ast o f the Isthm us o f

K ra on the M alay P eninsula. G o o d s were u n lo ad ed a n d then

tra n sp o rte d o n la n d p ro b ab ly crossing the narro w est passage

o f the isthm us a t K ra Buri in o rd er to reach the W est coast.

F ro m there ships sailed in the d irection o f the G u lf o f Bengal

36 H anshu,]. 28, 1671: É B l f P ï f t

x ít s í T É r r a a m e « «

m m i n m x

b r is is

u m

p a z,

ü ín i,

pi

»

i t

fis

SÄWD8, « m 2 . WJ&X, 9MÁ. X sliS îK îi

5t,

i«,

W E iiê K , ï m ê i t , m m

É Ü f M 'S Î T K A a m

« K tK

si b m ***#£.

m, t e m

F o r a n E nglish tra n sla tio n o f th e passage see Y ü Y ing-shi, Trade and

Expansion, 172-173, aiso Y ü Y ing-shi, “ H a n F o re ig n R e la tio n s” , in

D enis T w itchett, M ichael L oew e (eds.), The Cambridge H istory o f

China. Vol I. The C h ’in and Han E m pires, 2 2 1 B .C .-2 2 0 A .D .

(C am bridge: C am bridge U niversity Press, 1986), 376^162.

37 See for exam ple Y oshiaki Ishizaw a, “ C hinese C hronicles o f th e 1st—

5 th C en tu ry A D F u n a n , S o u th ern C a m b o d ia ” , in R o sem ary S co tt &

Jo h n G uy, S o u th E a st A sia & C hina: A rt, Interaction & Commerce.

Colloquies on A rt & Archaeology in Asia No. 17. H eld June 6th-8th,

1994. (L ondon: Percival D av id F o u n d a tio n o f C hinese A rt, 1995), 1131; P au l Pelliot, “ L e F o u -n a n ” , in Bulletin de VÉcole Française de

l ’Extrêm e O rient 3: 57 (1903), 248-303.

38 O n th e role o f O c E o, a m a jo r city o f F u n a n , see also Pierre-Y ves

M a n g u in , “ T he A rchaeology o f F u n a n in th e M ek o n g R iver D elta: the

O c E o C u ltu re o f V ietn am ” , in N . T ingley (ed.) A rts o f Ancient

Vietnam: From River Plain to Open Sea. (N ew Y o rk , H o u sto n : A sia

Society, M u seu m o f F in e A rts, H o u sto n , Y ale U niversity Press, 2009),

100-118; E ric B o u rd o n n eau , “ R éh ab iliter le F u n a n . O c E o o u la

p rem ière A n g k o r” , Bulletin de l ’École Française d ’Extrêm e-O rient 94

(2007), 111-157; or on th e large n etw o rk o f canals o f th e city th a t

actually req u ired a fu nctioning a n d centralized p o lity see also E ric

B o u rd o n n eau , “ T h e A n cien t C a n al System o f th e M ek o n g D e lta P relim inary R e p o rt” , in A n n a K a rlströ m a n d A n n a K âllén (eds.),

Fishbones and Glittering Emblems. Southeast Asia Archaeology 2002.

(Stockholm : M u seu m o f F a r E a ste rn A ntiquities, 2003), 257-270.

The “ C hina Seas” in w o rld history: A general outline

an d th en fu rth er to the east co ast o f Sri L a n k a or they reached

an o th er South In d ian p o rt, A rikam edu, o r an o th e r p o rt along

the coast o f C o ro m an d el.39 The re tu rn voyage h appened

accordingly o r via the M alacca Strait. F u n a n w as an im p o rta n t

stopover in the In d o -Ira n ia n a n d P a rth ia n sea tra d e o f th a t

tim e. A m ong the archaeological relics o f its form er cap ital d a ­

ted to the second to fo u rth century archaeologists excavated a

R o m an coin o f 152 A D w ith the im age o f the R o m a n E m p ero r

M arcu s A urelius (reg. 161-180). U n d o u b ted ly , this find does

n o t tell us anything a b o u t how a n d w hen the coin g ot there.

B ut there is also no convincing reason to deny the existence

o f a relatively ro b u st sea trad e in F u n an . B oth P a rth ia a n d In ­

dia are recorded in the Hou Hanshu as tra d in g w ith th e R o ­

m ans by sea an d conducting a very lucrative com m erce. The

seafaring trad e o f the R o m an E m pire, thus, finally connected

Southeastern E urope a n d the O rien t w ith the w est co ast o f In ­

dia, it connected the R ed Sea to the A ra b ian Sea a n d p o rts in

In d ia,40 a n d from there links existed th a t led into the C hina

Seas, even th o u g h they were n o t yet routine.

Human movement and migration

The sea - certainly also u n d e rsto o d figuratively in the sense o f

escaping to a rem ote place - including islands located close to

the litto ral b u t also countries like K o re a a n d Ja p a n were rela ­

tively early on considered or used as a place o f refuge or exile.

K ongzi f l~ p (551-479 BC) is claim ed to have already said he

w ould go into exile on the seas w ith a raft, should his political

ideas n o t be accepted (Lunyu ¡É l§ , B ook 5, chpt. 7).41 T he first

concrete case o f a n exile by sea is re p o rted fro m the year 473

BC. A fter the state o f Y ue h a d annexed W u, F a n Li j n f e , orig­

inally advisor to the victorious K ing G o u Jia n /ñ]£í, w ent over­

seas fearful o f the revengeful p ersonality o f the king {Shiji,

Y uew ang G o u Jian).42 W hen in 277 BC the state o f Q in c o n ­

quered the state o f Y ue in S o u th east C hina (m odern Z hejiang

an d F ujian), local in h ab itan ts are said to have fled in g reat

num bers overseas. O ne renow ned m o d ern histo rian , Z hang

X u n 5 8 Ü , even claim ed in this con tex t th a t the original settlers

o f the P enghu

Islands as well as o f T aiw an were originally

descendants o f these Y ue refugees w ho w ere k n o w n as fisher­

m en w ith sh o rt h air an d tatto o s. A first official state-sup p o rted

em igration to lands overseas is tran sm itte d from the th ird cen­

tu ry BC. E m p ero r Q in S hihuang is said to have sent a fleet

w ith 3000 young em igrants, m en a n d w om en, as well as w ith

grain, seeds an d a g rea t q u a n tity o f tools in the d irection o f J a ­

p a n .43 W hen D o n g Z h u o ü í (m urdered 193) to o k over

pow er th ro u g h a coup d ’é ta t to w ard s the end o f the E astern

H a n D ynasty, m any scholars a n d literati are said to have em i­

grated to L iaodong S í by crossing the B ohai Sea.

39 B e rn h ard D ah m , “ H an d el u n d H e rrsc h a ft im G renzbereich des

In d isch en O zean s“ , in D ie tm a r R o th e rm u n d , S usanne W eigelinSchw iedrzik (H rsg.), D er Indische Ozean. D as afro-asiatische M ittel­

m eer als Kultur-und W irtschaftsraum. (W ien: P ro m ed ia, 2004), 105—

122, here 109.

40 L iu X in ru , The Silk R oad in W orld H istory. T h e N ew O xford

W o rld H isto ry . (O xford: O x fo rd U niversity Press, 2010), 33 a n d 40.

41 Jam es Legge, The Chinese Classics. (Taibei: S M C Publishing,

1994), vol. 1.

42 Shiji, j. 41, 1740.

43 Shiji, j. 118, 3086.

69

M ilitary purposes

Follow ing the Zuozhuan

naval battles h a d becom e quite

p o p u la r by late E astern Z h o u times. In 549 BC K in g G ong f t

o f C hu M sent o u t his fleet to a tta c k the k ingdom o f W u

In

525 BC, W u

subsequently d isp atch ed its fleet twice to attack

C hu. I t has been calculated th a t betw een 549 a n d 476 BC a fu r­

th er 20 sea battles to o k place betw een W u a n d C hu alone.44

B ut we can say w ith relative certainty th a t the w ar ships n av ­

igated only in the close co astal w aters an d in river estuaries. A

real sea b attle d id n o t tak e place before 485 BC w hen F uchai

Í 7 Í , K ing o f W u

sent a fleet fro m the so u th a n d defeated

the navy o f the K in g d o m o f Qi pF in the n o rth (A igong

y ear 10). In 482 BC the K in g d o m o f Y ue M in the south a t­

tack ed W u from the sea a n d eventually defeated a n d annexed

the co u n try nine years later. All these references a tte st to the

use o f the seas a ro u n d C h in a fo r political m ilitary purposes,

b u t first only along the coastal line o f w h a t is now C hina.

B ut soon rulers v entured a b it further.

In 109 BC the E m p ero r H a n W udi d ispatched a fleet w ith

5000 soldiers from S h an d o n g via the B ohai Jfjl'jJf Sea to K o rea

in o rder to a tta c k the co u n try a n d establish C hinese prefec­

tures or com m anderies th ere.45 The C hinese soldiers were su p ­

posedly tra n sp o rte d to K o re a on m u lti-sto ried ships called

“ louchuan t§ |fn ” . S ubsequently, th e H a n E m pire established

three com m anderies o n K o re a n territo ry , L elang

Z henfan U S a n d L in tu n Emtfe.46 A lso a first C hinese occupation

o f the island o f H ain an , a t th a t tim e designated as D a n ‘er

a n d Z huyai, is recorded from H a n times. The cam paign to o k

place in the w in ter o f the year 6 o f the reign p erio d Y uanding

tQPft (112 BC) o f H a n W udi. T he Hanshu speaks o f 100,000

soldiers th a t are said to have p a rticip ated in the cam paign.47

E d w ard E. Schafer in this con tex t also m entions th e fam ous

H a n general M a Y u an M IS (14 B C -49 A D ) w ho w as involved

in m an y cam paigns in the south: “ These garriso n ed territories

seem to have been little d istu rb ed by th e im m igrants o f settlers

w ith th eir strange w ays durin g the earlier H a n period. B ut in

the first century o f the C h ristian era, after the definitive co n ­

quest o f those lands by the sep tu ag en arian hero M a Y iian,

the soldiers were follow ed by colonists a n d th eir m agistrates,

bringing all the p arap h e rn a lia o f official culture w ith them .

P arts o f N am -V iet to o k o n the superficial b u t pleasing aspect

o f a respectable Chinese province” .48 These exam ples clearly

a tte st to the fact th a t by H a n tim es a t the latest the Chinese

E m pire w as expanding its influence via the sea to close-by

44 Z h an g X u n , Zhongguo hanghai kejishi

■ (Beijing:

H aiy an g ch u b an sh e 1991), 23.

45 Shiji, j. 115, 2987-2989.

46 C oncerning th e developm ent o f these com m anderies see Lee Kib aik, A New H istory o f Korea. T ra n sla te d by E d w ard W . W agn er, w ith

E d w a rd J. Schultz. (C am bridge, M ass., L o n d o n : H a rv a rd U niv ersity

Press, 1984), 19-21; E rling v o n M ende, China und die Staaten a u f der

koreanischen H albin sel bis zum 12. Jh. Eine Untersuchung zur

Entwicklung der Formen zwischenstaatlicher Beziehungen in Ostasien.

(W iesbaden, F ra n z Steiner V erlag, 1982), 30-46; also Y ü Y ing-shi,

“ H a n F o re ig n R e la tio n s” , 451-457.

47 Hanshu, j , 6, 188; also W an g X iangzhi zE M -Z (Jinshi 1196 afterl2 2 1 ), Yudi jisheng flUSftSIIj. (Taibei: W enhai chubanshe, 1962),

j. 89, 2a.

48 E d w ard H . Schafer, The Vermilion Bird. T ’ang Im ages o f the South.

(Berkeley, L o s A ngeles: U niversity o f C alifo rn ia Press, 1967), 16.

70

neighbouring territories. The use o f the C hina Seas fo r naval,

m ilitary purposes has, thus, a long trad itio n .

D iplom atic purposes

Sources tell us m uch less a b o u t early p rivate trad e relations.

L ittle has been recorded - often we possess only indirect evi­

dence - an d also archaeology can so fa r provide us w ith only

m ore general tendencies. Officially a t least, m aritim e tra d e in

N o rth east A sia w as m o re o r less closely linked u p w ith

diplom acy.

F irst w ritten evidence o f a visit o f a Japanese envoy to C h i­

na stems from the year 57. In the H ou H anshu it is m entio n ed

th a t the W o \* - this is the old C hinese d esignation o f Ja p a n h ad b ro u g h t tribute to the C hinese co u rt th a t year. T he H a n

E m p ero r G uangw u A iK (reg. 25-57) is even said to have c o n ­

ferred, via the Japanese envoy, a golden seal to the “ K ing o f

W o ’’.49 A n inscription confirm ed the Japanese ru ler as the king

o f his country. T his w ritten reco rd seem ed to have been veri­

fied w hen in 1784 a golden seal w as u n earth ed o n the Island

o f S hika-no-shim a /Cu' M t-5) in Ja p a n - supposedly exactly the

sam e seal th a t h ad been conferred u p o n the Japanese king

by the H a n em p ero r.50 In d eed this seal has m eanw hile been

considered as authen tic am ong J a p a n ’s archaeological experts;

a solid p ro o f th a t this really is the seal th a t is m en tio n ed in the

H ou H onshu is this, how ever, adm ittedly not.

A s trib u te the Japanese are said to have sent goods such as

textiles, sapan w ood, bow s a n d arrow s, slaves, a n d w hite

pearls. C hinese gifts o n the o th er h a n d included silk fabrics,

gold objects, bronze m irro rs, pearls, lead a n d c in n a b a r.51

B ronze m irrors as well as num erous o th er bronze a n d iro n o b ­

jects stem m ing from the H a n perio d have been excavated in

various places in b o th K o rea a n d Jap an . U n d o u b ted ly , bronze

m irro rs co n stitu ted one o f the early trad e com m odities an d

diplom atic gifts o f the tim e. Even b ronze coins cast u n d er

the rulership o f W ang M an g j/Ef? (r. 9 -23) have been u n ­

earth ed from some places in K y ü sh ü A W -52

T he C hina Sea w as o f course also used by fisherm en since

earliest times. C oastal residents o f S handong, Jiangsu a n d Z h e­

jian g obviously w ere highly qualified shipbuilders a n d already

d u ring Z h o u tim es w ere using the coastal w aters fo r fishing

an d tra d in g .53 B oats fo r tw o can p ro b ab ly be d ate d b ack to

the E astern Z h o u D y n asty Í J 1 ] (770-221 v. C hr.). Relics o f

49 H o u H anshu, j . 85. 2821. T his seal is to d a y on display in the

H isto rical M u seu m o f F u k u o k a . Ja p an . F o r the historical assessm ent

o f th e seal cf. Seyock A u f den Spuren der Ostbarbaren. Z u r Archäologie

protohistorischer Kuituren in Südkorea und W estjapan. (M ünster:

L itV erlag .. 2004). 207-211. B u n k a. T ü b in g er in terk u ltu relle un d

linguistische Ja p an stu d ien . Illu stra tio n s m ay be d o w n lo ad ed from

h ttp ://w w w .w e b .n c h u .e d u .tw /~ le e h sin /Ja p a n -l.h tm . http ://w w w .o to m iy a .c o m /fish in g /g u id e /g u id e l3 .h tm l. h ttp ://w w w .w w w 3 .fam ille .n e.

jp /~ o -k o g a /k u m a /k ira m e k i/S u p e r-H is to ry /s h _ 0 1 .h tm , h ttp ://w w w .

b fo rtu n e.n et/so cial/seso /n ih o n -ed o /k in in .h tm .

30 YÜ Y ing-shi. Trade and E xpansion in H an China. 186; A lfred

W ieczorek, S ah ara M a k o to . Z e it der M orgenröte. Japans Archäologie

und Geschichte bis zu den ersten Kaisern. (M annheim : R eiss-E ngelhorn

M u seu m . 2004). 225.

31 H o u H anshu. j. 30. 857-858.

3~ Y ü Y ing-shi. Trade and E xpansion in H an China. 186.

33 Z h an g X u n . W oguo gudai haishang jiaotong. 3 4.

A. S chottenham m er

ru d d ers are m u ch older a n d have been estim ated to date back

to 7000 BC o r earlier.

M ig ratio n , m ilitary, political-diplom atic a n d com m ercial

p urposes were, thus, the d o m in atin g factors o f activities in

the C hina Seas in this early period. T he sources provide us

w ith the im pression th at, officially a t least, m ilitary an d d ip lo ­

m atic purposes prevailed while trad e w as only o f m in o r im p o r­

tance. T his certainly does n o t reflect the w hole range o f the

picture. A n d it is clear th a t official relations w ent along w ith

cu ltural exchange, a fac to r th a t becam e ever m ore im p o rtan t

parallel to the sharp increase in com m ercial interchange an d

interaction. The routes still closely follow ed coastlines a n d is­

lands in the m o re shallow w aters.

The period o f division (Sanguo - 1 , 220-265, 280; Nanbei chao

T his p erio d is ch aracterized by grow ing official a n d non-offi­

cial relations w ith K o rea a n d Jap a n , w hich rose as independent

states at th a t tim e, a process th a t w as also facilitated by

increasingly frequent travels o f B uddhist m onks. A s K orea

a n d Ja p a n converted to B uddhism , C hina becam e a m ajo r pil­

grim age d estin atio n fo r m o n k s seeking edu catio n an d texts

a n d , thus, also increasingly fu nctioned as a m e d ia to r o f C h i­

nese culture. The C hina Seas were used increasingly fo r private

voyages a n d increasingly fu nctioned as a cu ltu ral exchange

zone. G o o d s a n d technologies in tro d u ced to these countries

by m erch an ts u n d o u b ted ly greatly facilitated the a d o p tio n o f

C hinese culture th ro u g h o u t the C hina Seas.

A t th a t tim e, K o rea w as divided in to three kingdom s,

K o g u ry ö

(37 B C -668 A D ), Silla fffH (57 B C -953

A D ) an d Paekche 5 Î Ü (18 B C - 660 A D ). M u tu a l relations

w ith C hina a n d Ja p a n were, generally speaking, characterized

by m ilitary considerations. T he C hinese state o f W ei t f (220—

265) a tta c k e d K o rea, in p artic u la r K o g u ry ö th a t h a d a jo in t

la n d b o rd e r w ith C hina, a n d vice versa. All three K o re a n king­

dom s, on the o th er h an d , tried to tak e ad v an tag e o f C h in a’s

separatio n a n d use nom adic peoples as well as Ja p a n fo r its

ow n m ilitary purposes. P aekche, fo r exam ple, asked fo r J a p a ­

nese tro o p s to assist in attack in g Silla.54 P aekche also devel­

oped as the sp rin g -b o ard fro m w hich aspects o f Chinese

culture as well as B uddhism w ere fu rth e r tran sm itted to Japan.

B ut despite these n o t really pacific politics th a t continued

th ro u g h o u t the N an b eich ao p eriod, it w as a tim e w hen the ru l­

ing a n d social elites in K o rea a d o p te d m an y elem ents o f C h i­

nese culture as well as Buddhism .

W ei also m ain tain ed official relatio n s w ith Jap an . Twice the

W ei ru ler sent em bassies to Ja p a n , betw een 238 an d 247 an d

vice versa fo u r Japanese em bassies cam e to C hina. The chapter

“ D escrip tio n o f the E astern B arb arian s’’ (D ongyi zhuan í H

ÍS) in the W ei annals o f the H istory o f the Three Kingdom s

(Sanguo zh i ^ . H / S ) described the W o \* people in relative d e­

tail. The various peoples o f the W o co u n try , it is said, can be

reached, as a rule, by each tim e crossing an o th e r sm all sea. The

geography a n d the m o st im p o rta n t local p ro d u cts are d e­

scribed, as well as the n u m b er o f households, if know n, the

nam e o f the responsible official, as well as distances. T he W o

co u n try is m entio n ed as the co u n try o f the Q ueen H im iko ^

34 K i-b aik Lee. A N ew H isto ry o f Korea, 45-46.

The “ C hina Seas” in w o rld history: A general outline

SSof, supposed to have been located in the regions o f X iem ayi

ï f P J f ï , in Japanese Y a m a ’ichi.55

J a p a n ’s contacts w ith C hina fo r a long tim e w ere m a in ­

tained basically via K orea. This has o f course also to do w ith

the m anaging o f the sea routes. It w as easier to sail along the

coasts a n d passing islands th a n to tak e the d irect sea ro u te via

the open sea, a ro u te th a t w as first officially tak en in T an g

times. J a p a n ’s interest in K o re a in this respect basically only

existed in her role as interm ediary to C hinese culture. O ne

w as interested in scholars, books, calendars a n d a rt objects.

It w as also via K o rea th a t B uddhism reached Ja p a n , m ainly

via Paekche. A last Japanese em bassy to C h in a h a d reached

the c o u rt o f the W estern Jin Ë § et (265-316) in 266, a follow ing

em bassy is n o t m entio n ed before 413, w hen it reached the

c o u rt o f the E astern Jin # j8 r (317-420).56

W ith the unification o f N o rth C hina u n d er the T oba-W ei

IÏISÎÜ! (386-534) the N o rth e rn Bei W ei state becam e K oguryö’s m ost im p o rta n t p artn er. A fter 425 fo r m o re th a n a cen­

tu ry regular tribute a n d trad e relations existed betw een b o th

countries. A t the sam e tim e, K oguryö tried to m ain ta in d ip lo ­

m atic relations w ith C h in a’s S o u th ern dynasties, w h at tu rn e d

o u t to be n o t as easy as hoped. In 480 a n d 520, fo r exam ple,

tw o em bassies o f K og u ry ö to the S o u th ern Qi a n d th e L iang

D ynasty were cau g h t by the Bei W ei.

The influence o f C hinese civilization, as well as im m igrants

from b o th C hina an d K o re a th a t were tro u b led by w ars b e­

tw een 365-645, left far-reaching signs in the h ith erto still re la ­

tively prim itive an d trad itio n ally organized Japanese society

th a t w as based u p o n a clan system (uji Be). A Japanese w o rk

datin g from 815, the Shinsen shoji roku U f í S t t É ü , contains

genealogies o f 1182 aristo cratic people from K y o to a n d five in ­

ner provinces. M ore th a n 30% o f these aristo cratic fam ilies

w ere o f foreign origin (bambetsu jÇSll), 176 from C hina, 120

from P aekche, 88 from K o m a (K oguryö) a n d 18 from Silla.

A lso num erous K o rea n peasan ts a n d craftsm en em igrated to

Ja p a n d u ring this tim e.57

D u rin g this tim e period, the E ast C hina Seas also started to

becom e the spring-bo ard fo r locations b eyond in S o u th east

Asia. In this context, it is intriguing to see th a t the Chinese

ch aracter fo r ocean-going ju n k “ bo IfÉ” seems to a p p e a r for

the first tim e in the th ird century. In 260, K an g T ai 1 * ^ , re ­

ceived the o rd er o f the ruler o f W u, Sun Q u an J S Ä (reg.

222-252), to travel to S o u th east Asia. H e left a re p o rt a b o u t

his travels, the Wushi waiguo zhuan

(Description

o f foreign countries during the time o f Wu), p arts o f w hich have

55 M a tsu sh ita K e n rin I ß T M W , w h o in tro d u c e d th is tex t in to

Ja p an ese scholarship, su p p o sed th a t th e last character, “y i S ” , w as

a ty p o a n d rep laced it by the ch aracter “ tai -¡e ” . F ro m th is the nam e

Y a m a ta i fo r th e la n d o f th e Q ueen o f th e W o resulted, a nam e th a t has

rem ain ed in use u n til to d a y despite critical tex tu al analysis. L ater in the

fifth cen tu ry Y a m a to in C e n tral J a p a n w as th e seat o f the central

Ja p an ese governm ent. In th is co n tex t it h as b een suggested th a t the

Y a m a ta i o f th e W ei A n n als is actually identical w ith Y a m a to . M o re

recen t research, how ever, claim s th a t th e Y a m a ta i o f th e W ei A n n als

ra th e r referred to th e n o rth e rn p a r t o f K yüshü. B u t even tak in g in to

co n sid eratio n arch aeo logical evidence, the residence o f H im ikos,

Y a m a ’ichi, c a n n o t be identified w ith ab so lu te accuracy.

56 Jean R eischauer, R o b e rt K a rl R eischauer, Early Japanese H istory,

40 B C - 1167 A D . (G loucester, M ass.: P eter Sm ith, 1967), 17.

57 Jean R eischauer, R o b e rt K a rl R eischauer, Early Japanese H istory,

19-20.

71

survived in later encyclopaedias. A n en try in the Taiping yulan

A ^ H ÍP IÍ by Li F a n g * 1 © (925-996) provides us w ith a b rief

passage o f the Wushi waiguo zhuan. A ccordingly, a t th a t tim e

overseas ju n k s existed th a t were equipped w ith seven sails (IfÉ

‘jfi'fc'lft).58 A n o th er entry quotes th e Nanzhou yiwu zhi Iff M U

f lk S by W a n Z h en Ä H an d speaks o f people b eyond C h in a’s

b orders, w hose ships w ere equipped w ith u p to fo u r sails

according to th eir size ( 9 f 'i k A P S Ä ^ /J''^6i/F H l,Ä ).59 Sun

Q u an rep o rted ly already possessed ships o f a size to be able

to tra n sp o rt up to 3000 soldiers a n d officials a n d could sail

along the big rivers an d stream s (A lfp ^ T ifE IÄ ^ iftE IA lfä id c

^ ¡ t 2 ± H ^ A | S | P E e * ï I ï t ) . 60

Interestingly, the c h aracter fo r “ho IfÉ” is w ritten in tw o dif­

ferent w ays in the Wushi waiguo zhuan ( 0 AíÉlfÉ'jfi'fc'llR; see

also Nan Q ish u ,j. 11, 195: )fÉ, Ê tË ), w hich m ay suggest th a t

it originally em erged fro m a certain p honem e (in C antonese

p ro n o u n ced “ b a h k ” ), p erh ap s by a d o p tin g a foreign language

term related to the A rab “ b a h r” o r the G reek “ b a ris” . A ccord­

ing to Pierre-Y ves M an g u in, th e expression “kolandio phonta”

in a passage in the Periplus o f the Erythrean Sea has been in ter­

preted as a c o rru p t G reek form “ kunlun bo H, S lfÉ ” , referring

to ships th a t sailed from In d ia to S o u th east A sia.61 They are

described as ships u p to 50 m in length, carrying ab o u t

300 to n s o f goods a n d hun d red s o f passengers, equipped w ith

m ultiple sails a n d m asts a n d plan k s fastened w ith vegetal fi­

bres.62 N au tica l archaeologists call these vessels “ stitchedp lan k a n d lashed-lug tech n iq u e” .63 F o reig n shipbuilding tra d i­

tions consequently greatly influenced S o u th C h in a’s sh ipbuild­

ing industry. As late as the T an g D y n asty coastal people o f

G u an g d o n g learned how to build ju n k s w ith o u t using nails,

nam ely by tying to g eth er planks a n d beam s w ith the fibres o f

58 Taiping yulan A W I b y Li F a n g Í B S (925-996), j . I l l , 5b, S itu

congkan, fasc. 35-55.

59 Taiping yulan, j. I l l , 5b.

60 Sanguozhi buzhu

by H a n g Shijun IjttË S I. (Shanghai:

S hangw u yinshuguan, 1937), j. 6, 6b (1023).

61 Pierre-Y ves M a n g u in , “ S o u th east A sia n shipping in th e In d ia n

O cean d u rin g th e 1st m illennium A D ” , in H im an sh u P ra b h a R ay an d

Je an -F ran ço is Salles (eds.), Tradition and Archaeology. Early M aritim e

Contacts in the Indian Ocean (L yon/N ew D elhi: M a n o h a r/M a iso n de

l’O rien t M é d ite rran éen /N IS T A D S , 1996), 181-198, here 190. Ia n

G lo v er early on h a d already tu rn e d sc h o lars’ a tte n tio n to th e role o f

S o u th east A sia as a link betw een In d ia, S outheast A sia a n d beyond;

see his E arly Trade between India and Southeast Asia: A L ink in the

D evelopm ent o f a W orld Trading System . (H ull, U niversity o f H ull,

C e n tre for S o u th east A sia n Studies, 1989). Occasional paper, N o . 16.

62 F o r a d escription see Pierre-Y ves M a nguin, “ T he S o u th east A sian

Ship: A n H isto rical A p p ro a c h ” , Journal o f Southeast Asian Studies 11

(2) (1980), 266-276; also P au l P elliot, “ Q uelques textes chinois

co n cern an t l’In d o ch in e hindouisée” , in Etudes asiatiques publiées â

I” occasion du vingt-cinquièm e anniversaire de l ’Ecole Française

d ’Extrêm e-Orient. (Paris: E F E O vol. II, 1925), 243-263.

63 See Pierre-Y ves M a n g u in , “ S o u th east A sia n S hipping in th e In d ia n

O cean durin g the 1st M illen n iu m A D ” , 184ff; also Pierre-Y ves M a n ­

guin, “ T rad in g ships o f th e S o u th C h in a Sea: Shipbuilding T echniques

a n d th eir R ole in th e D evelopm ent o f A sian T ra d e N e tw o rk s” , Journal

o f the Economic and Social H istory o f the Orient, 36 (1993), 253-280;

on the role o f th e M a lay P eninsula in early m aritim e tra d e relatio n s see

also M ichel Ja cq -H e rg o u alc’h, tra n sla te d by V icto ria H o b so n , The

M alay Pensinsula: Crossraods o f the M aritim e Silk R oad ( 100 BC-1300

A D ). (Leiden, B oston, K öln: E. J. Brill, 2001).

72

A. S chottenham m er

the “guanglang tfúW tre e ” , a k in d o f pallii (Arenga pinnata).64

T he greatest perio d o f ad vancem ent in C hinese shipbuilding

technology occurred durin g the Song a n d Y u a n dynasties.65

T he m ost fam ous C hinese overseas vessels are th e so-called

“ sand ships” (shachuan î'M'p) fo r shallow w aters, the “ b ird

ships” {wu o r niaochuan JM S) w ith a sharp b o tto m , proficient

in sailing in the open w aters, as were th e “ F u ch u a n Im fp” (F u j­

ian ships) th a t w ere equipped w ith a keel a n d th e “ G uangchua n l # | p ” (G uangdo n g ships) - b u t these have basically to be

d ated into the Song dynasty (960-1279). Song ships, as the fa ­

m ous Q u anzhou shipw reck th a t w as excavated in 1974 o ff the

coast o f Q u anzhou (Q u an zh o u Flouzhu Song chuan

7 ^ |p ) m ay show , w ere already divided by b u lkheads in to ship

co m p artm en ts.66

Som e tim e later, we m eet the expression also in O fficial H is­

tories o f the N anbei chao period, such as in the Songshu 5 ^ # ,

the N an Qishu IflP F lr, the Jinshu t a l r o r the Liangshu § Î J r .67

A nalysing the q u o tatio n s fro m these histories we learn th a t

b o th p rivate m erch an ts a n d official persons crossed the sea

on such bo |É . The Liangshu, fo r exam ple, explicitly speaks

o f foreign m erchan ts (9M H M À ) w ho arriv ed on bo a n d also

m entions the m ultiple profits th a t could be m ade from m ari-

64 Jam es K . C h in . “ P o rts. M e rch a n ts. C hieftains, a n d E unuchs.

R ead in g M aritim e C om m erce o f E arly G u a n g d o n g ". 222-223.

63 Jacq u es D ars, “ L es jo n q u e s chinoises de h a u te m er sous les Song et

les Y u a n " . Archipel 18 (1979). 41-56; also Pierre-Y ves M a nguin.

“ T rad in g Ships o f the S o u th C h in a S ea" (1993). F o r the h isto ry o f

shipbuilding techniques in E ast A sia also J u n K im u ra, “ H istorical

developm ent o f shipbuilding technologies in E ast A sia ", c h a p te r 1.

d o w n lo ad ed via http ://w w w .sh ip w reck asia.o rg /w p /d o w n lo ad .p h p 7 id

(31.08.2012), w here a few concrete w recks are in tro d u ced . H isto rian s

a n d u n d erw ater arch aeologists including J u n K im u ra. X i L ongfei. Cai

W ei. Sally C h u rch a n d oth ers also sta rte d a w ebsite, see h ttp ://w w w .

shipw reck asia.o rg /p rojects/.

66 See fo r exam ple the excavation re p o rt in F u jian sh en g Q u an zh o u

haiw ai jia o to n g sh i b o w u g u an

(ed.).

Quanzhouwan Songdai haichuan faju e yu yanjiu J f t 'M íS ^ í lf /í f tn f íí E

(Beijing: H aiy an g chubanshe, 1987).

67 Songshu, i . 97. 2377: Ü J S > S Ü H . A Í É f i X 'M X l f S t S l f . S *

î f W H A . fflA H tB E A M .

M M E W fr];

Songshu, j. 97. 2380-81: A í ü — A .

Æ rË P S ? .

II

E m fit i t i fit PS S : Nan Oishii, j. 11. 195: H JfT ffiE

& Ï Â îf îf lf iâ É L M , Ê ff i. T - I f ö f n s ê llE r Î T Ê i Î J M: Nan Oishii,j.

31. 573:

Í l í £ í 5 m P S j É $ l f 'M ît: Nan Oishii. /.

41. 724:

Î R « B S i S î i . Í#At*fÉÍfi. Ü f f i x A I : Nan

Oishii, /. 58. 1015: X B : r g / H t a í í » * I ^ Í T # M * S , . X 2 5 M A f? iW

» A S î I Î 'J W g . H U P E Ä Ä .

W M M : Nan Oishu. i. 58: 1018: Î Ë / B : « # r ^ j g ^ g j . g i t j j g

m i s . M B s m s î i f s . ¿ m ä h s s . p s m m . î u t t S A . « o j p i » . it w - z s

@. H â â j â l i . Ç iÈ IÎI'W . É Â X J â S â :. f f l f S ï J # : Jinshu, /. 97. 2547: Ä

s tm

M im

tim e trad e, basically by buying cheaply a n d th en reselling the

g oods fo r higher prices {Liangshu, j. 33, 470). A lso C hinese pil­

grim s like F ax ian } ¿ H (c. 337-422) p rovided descriptions o f

these ocean-going vessels. This is a clear indicatio n fo r th a t

states n eighbouring the C hina Seas started to venture into this

b o d y o f w ater on a m o re reg u lar basis betw een the 3rd an d 5th

century A D .

T he C hina Seas were increasingly used fo r p rivate com m er­

cial activities - reflecting, according to o u r thesis, a general te n ­

dency aw ay fro m official m ilitary, political a n d diplom atic

relations to w ard s m o re p rivate exchange - alth o u g h, as m en ­

tio n ed above, the C hinese basically still rem ain ed passive

receivers along the coast, especially as far as relations w ith

the N a n h a i are concerned. B ut it is u n d isp u ted th a t m ajo r

changes to o k place in the C hina Seas du rin g this period. A lso

the increasing im p o rtan ce o f B uddhism has to be m entioned.

W ang G u ngw u provides a very g o o d overview o n early C h i­

nese trad e in the N a n h a i a n d the g rad u al rise in im portance

o f B uddhist religion, culture a n d com m odities.68

In Ge H o n g ’s ÎIÎÂ (284-343) Shenxian zhuan fíflllflí {Re­

cords o f D eities), the D ao ist im m o rtal M a G u

once told

a n o th e r im m o rtal, W ang Y u an ÿEüâ, th a t since m eeting him ,

the E astern Sea h a d been tu rn e d in to m u lb erry fields three

tim es.69 F ro m this story com es an old C hinese saying, “canghai

sangtian i l î i f JgEB” , w hich literally m eans tu rn in g the sea into

m u lb erry fields, b u t w hich has been w idely used to indicate any

great tran sfo rm atio n . The th ird to appro x im ately the early sev­

en th centuries w ere in fact a p erio d o f g reat changes in the C h i­

na Seas. In this context we can speak o f a perio d o f the com ing

to g eth er o f the E ast a n d the S o u th C hina seas as well as its

g rad u al linking up w ith the In d ia n O cean, the g rad u al grow ing

to g eth er o f w h at h a d form erly been a “m aritim e p atch w o rk ”

(Flickenteppich), to use the w o rd o f m y colleague R oderich

P ta k .70

Early middle period China (Sui-Tang)

D u rin g the Sui D y nasty ß/| (589-617) official a n d diplom atic

relations still seem ed to prevail. B ut p rivate traffic, especially

o f m o n k s a n d m erch an ts, increased. The first Sui E m peror,

W endi X i ? (r. 581-604), still co n cen trated o n the consolida­

tio n o f the newly unified em pire. In 598, he sent tro o p s to K o r­

ea o n b o th lan d a n d sea routes to subdue the country.

G enerally, he looked to w ard s n o rth C hina a n d the w ealth o f

the so u th ra th e r seem ed to have been a th o rn in his flesh. In

598, he even tried to restrict m aritim e com m erce in the south

by p ro h ib iting the co n stru ctio n o f large ships. All ships th a t

w ere built in the so u th an d were longer th a n 30 Chinese feet

w ere confiscated ( Â Î I U lî^ W , A f f l % f r p Ä H 5 t E i l , S I S A

HT).71 H ow ever, this is n o t only a clear sign o f the existing

f f i A î f : Liangshu, /. 33. 470: A l s « .

« * . Ç É b S ifîiA m .

ÿ P H H A I îl

HÄÄ.

X W M B P * . Â i 'J I W E S K È l Ü f f i :

Liangshu, j . 54. 787: m m . Î I Ü Î B A » t A » M . 1 ® * * * ) * * . »8

Liangshu, /. 54. 788: í * |f [ S Í Q * § § . ... Â l t Î M H .

m,

S I H A M A » . îI Ü S iE B P lg j* .. . «

i m m m x m , ® A i* m * h g . » h a " _ j i m s . m i z ,

Ä M . ..: Liangshu. /. 56: 842:

^ » A M /lM . JI* S M .

á s m

ü ïîs m m m * . É L ± T m m m t

IB .

ÍÍÍÍSJsí'Íb. P au l Pelliot. “ L e F o u -n a n " , in Bulletin de

l'École Française de l'Extrèm e Orient 3:57 (1903). 248-303. here 271.

277; Shuijing :hu 7 k J î î i by Li D a o y u a n iß iÜ T t (late 5th or early 6th

century), j. 1. 9a.

68 W an g G u ngw u. “ T he N a n h a i T rade: A S tudy o f the E arly H isto ry

o f C hinese T rad e in th e S o u th C hina S ea". Journal o f the M alayan

Branch o f the R oyal A siatic S ociety 31:2 (1958). 1-135; also L iu X in ru ,

The Silk R oad in W orld H istory, 60-61.

69 Shenxian zhuan W idliH by G e H o n g H Î # (284-343). in S h o u Y izi

Z — ~p (ed.), D aocang jinghualu

(H angzhou: Z h ejian g guji

chubanshe. 1990). B o o k 2. j . 2, 7.

70 R o d e rich P tak . D ie m aritim e Seidenstra&e. (M ünchen: C .H . Beck

V erlag. 2007). 54.

71 Suishu P H # by W ei Z heng * 1 ® (580-643). (Beijing: Z h o n g h u a

shuju. 1997)../. 2. 43.

The “ C hina Seas” in w o rld history: A general outline

com m ercial w ealth in th e so u th th a t accrued fro m m aritim e

trade; this political m easure also attests to the fact th a t the

sea w as regarded u n d e r political criteria b u t th a t a t the same

tim e trad e relations th a t h a d developed m o re o r less in d ep en ­

dently contin ued to exist.

M ilitary purposes

The second Sui E m peror, Y angdi

(r. 605-617), how ever,

actively p ro m o ted m aritim e trad e a n d “ called fo r m en to

establish contacts w ith far-aw ay regions” .72 Several m issions

w ere sent to various countries in S o u th east Asia. A lth o u g h

he, too, used the sea fo r m ilitary p urposes (in 612, 613 a n d

614 in the three cam paigns th a t w ere u n d erta k en to K o rea)

an d h undreds o f ships are said to have been co n stru cted to sail

from S handong to K o rea, Y angdi a t the sam e tim e p a id g reat

atte n tio n to the w ealth th a t could be derived fro m m aritim e

trade.

H e eventually also ord ered th e co n stru ctio n o f a fleet a n d

u n d erto o k m ilitary expeditions to L iuqiu ïJfcïR.73 It is still u n ­

clear to w hich island this actually refers, the R y ükyü Islands or

T aiw an. U n til to d ay scholars have n o t arrived a t a definite

conclusion. A ccording to T s’ao Y ung-ho

the m ajo rity

o f historians considers it to be T aiw an .74 T his is a t least the

first tim e th a t L iuqiu is officially m entio n ed an d , thus, an o th e r

p a rt o f the E ast C h in a Seas w as explored fo r the first tim e offi­

cially. H ow ever, the m ission w as n o t successful. A lo t w as

ap p aren tly destroyed a n d th o u san d s o f captives tak e n w ho

w ere later tak en to C hina as slaves. B ut n o trad e o r d iplom atic

relations w ere established. W hen the Chinese arm y proceeded

fu rth er in to C hinese territo ry - if we accept th a t this entry

actually referred to T aiw an - m o st o f the soldiers were infected

w ith m alaria or died o f o th er diseases.75 A fter this cam paign,

T aiw an a t least officially seems to have disap p eared ag ain from

Chinese consciousness.

D iplom acy

W hen the ruling elite o f Ja p a n cam e to know a b o u t the unifi­

catio n o f C hina, betw een 581 a n d 600 a first em bassy w as sent

to the C hinese court. In 607, d u rin g the reign o f the Japanese

Q ueen Suiko H ilii (592-628; according to N elson) w ith O no

no Im o ko 7 M f Ä “P, the first official Japanese envoy w as sent

to the C hinese court. The Japanese letter th a t w as h a n d ed over

to the C hinese em pero r designated Ja p a n as the “ C o u n try o f

the R ising S un” , while C hina w as addressed as “ C o u n try o f

the Setting S un” . Im o k o referred to the C hinese em p ero r as

“ the B odhisattva Son o f H eaven w ho dedicates his full pow er

to the su p p o rt o f B uddhist teachings” . N evertheless, the letter

w as seen as a bone o f co n ten tio n , as, in the eyes o f the Chinese,

the Japanese ru ler h a d placed him self o n the sam e level w ith

the C hinese Son o f H eaven. B ut in spite o f d iplom atic irrita ­

tions a n d the alleged insult, E m p ero r Y angdi sent his ow n en ­

voy, Pei Shiqing S t Ë 'i f , b ack to Ja p a n w ith O no in 608. They

72 S u ish u J. 82, 1817.

73 Suishu, j. 81, 1822-1823 (D ongyi # 5 1 ) states:

ItiÉ S iïW i,

74 T s’a o Y u n g -h o ffzIcíD (C ao Y onghe), Zhongguo haiyangshi lunji

Í ’S S ÍÍ Í P Í ! s itlíí. (Taibei: L ian jian g chubanshe, 2000), 40.

75 Suishu, j. 24, 367.

73

sailed via S handong, Paekche S Í H , T sushim a l i f t a n d Iki ■§

l í fu rth e r east. T his m eans th a t they still to o k the ro u te along

the coastline a n d islands avoiding deep w aters. Pei Shiqing la ­

ter b ro u g h t some Japanese students w ith him w ho th en spent

som e tim e in C hina a n d learn t th e basics o f C hinese culture.

In this context, we see th a t the sea ro u te from Ja p a n to C hina

also w as startin g to becom e a ro u te fo r scholars a n d people w ho

w ere in search o f know ledge a n d B uddhist teachings. Official

students fro m K o re a a n d Ja p a n cam e to C hina to learn ab o u t

B uddhism a n d C hinese culture. Ja p a n a d o p ted n o t only a rt

a n d culture from C hina b u t m ore o r less its com plete adm inis­

trativ e system. C ertainly the m o st fam ous Japanese m onk

w ho cam e to C hina a t th a t tim e w as E nnin H i t (c. 793-864),

w ho left us an interesting diary a b o u t his travels in the T ang em ­

pire. A m ong C hinese m o n k s w ho w ent to Ja p a n Jianzhen H H

(688-763) has to be m entioned. All this attests to the im portance

o f culture a n d religion in m u tu a l exchange relations. T rad e rela­

tions o f th a t tim e were also greatly influenced by B uddhism ,

B uddhist texts a n d artefacts ranging highly am o n g them . A t

the sam e tim e, the sea routes expanded on a p e rm an en t basis

to places such as In d ia a n d the Persian G ulf.

Between 623 a n d 684 alone num ero u s m issions n o t only

from In d o -C h in a b u t also from countries fu rth e r aw ay reached

C hina, such as Jav a H eling ¡°[® , P an p a n S S , Juloum i H¡]jl

§5, D a n d a n H H o n the M alay P eninsula, Srivijaya (Sanfoqi

a n d Jam bi (M o luoyou U (^ )H ïB Ï(S I)) o n Sum atra.