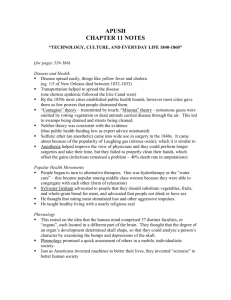

11 Technology, Culture, and Everyday Life, 1840–1860 I

advertisement