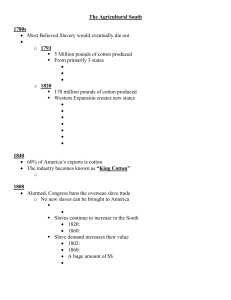

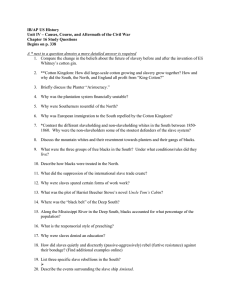

12 The Old South and Slavery, 1830–1860 I

advertisement