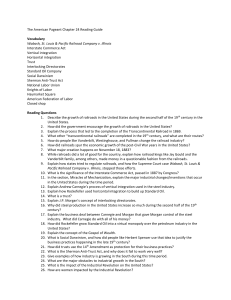

Industrial America, 1865-1900: Rise of Corporations & Labor

advertisement