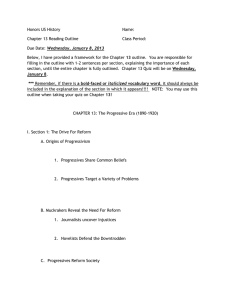

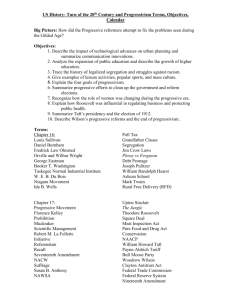

21 The Progressive Era, 1900–1917 I

advertisement