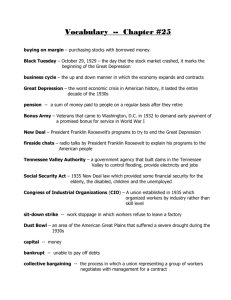

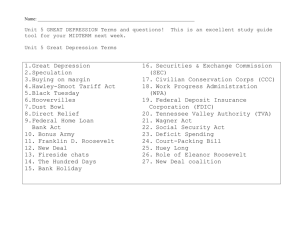

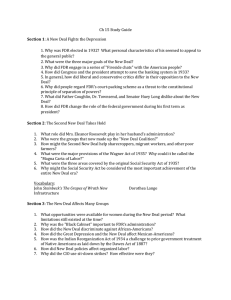

24 The Great Depression and the New Deal,1929–1939 R

advertisement