The Portrayal of Colombian Indigenous Amazonian Please share

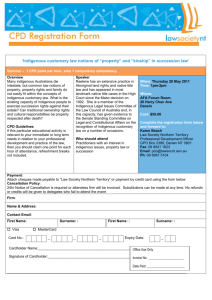

advertisement