Document 11676844

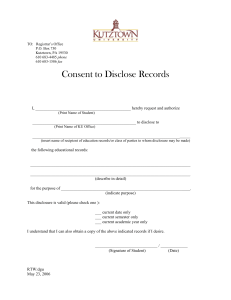

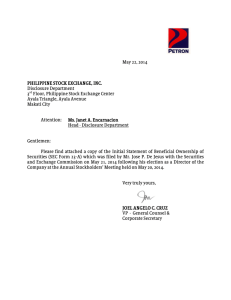

advertisement