Montana’s Forest Products Industry and Timber Harvest, 2009

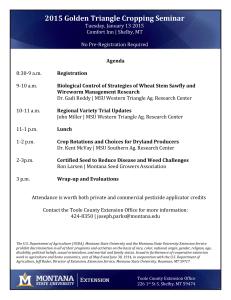

advertisement