Document 11673671

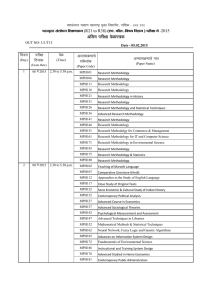

advertisement