INDIAN EDUCATION JOURNAL OF CONTENTS

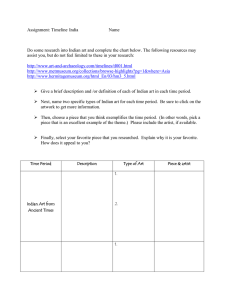

advertisement