Document 11671618

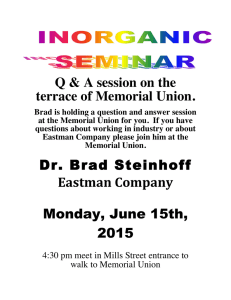

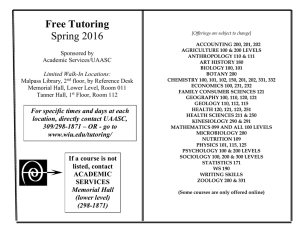

advertisement