NCERT i r First

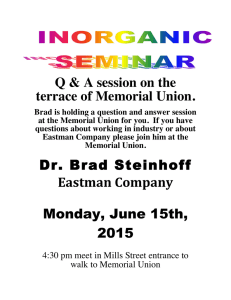

advertisement