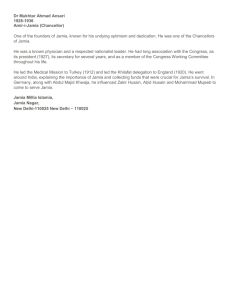

NCERT Memorial Lecture Series First Zakir Husain Memorial Lecture – 2007 1897-1969

advertisement