O M V

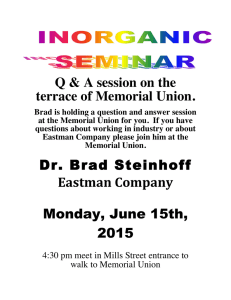

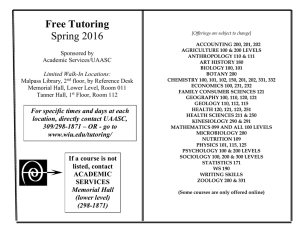

advertisement